To describe levels of nitrate and trace elements in drinking water from the study areas of a multicase-control study of cancer in Spain (MCC-Spain).

MethodsA total of 227 tap water samples were randomly collected from 67 municipalities in 11 provinces and the nine most frequently consumed bottled water brands were sampled to measure levels of nitrate, arsenic, nickel, chromium, cadmium, lead, selenium and zinc.

ResultsThe median nitrate level was 4.2mg/l (range<1-29.0), with similar levels in rural and urban municipalities (p=0.86). Trace elements were unquantifiable in 94% of tap water samples. Differences between areas were significant for nitrate (p<0.001) and arsenic (p=0.03). Only nitrate was quantifiable in bottled water (range 2.3-15.6mg/l).

ConclusionsNitrate levels in municipal water differed between regions and were below the regulatory limit in all samples, including bottled water. Trace element levels were low and mainly unquantifiable in tap and bottled water.

Determinar las concentraciones de nitrato y de elementos traza en el agua de consumo de las áreas del estudio Multicaso-Control de Cáncer en España (MCC-Spain).

MétodosSe tomaron al azar 227 muestras de agua municipal en 67 municipios de 11 provincias, y 9 muestras de las aguas embotelladas más consumidas, para cuantificar la cantidad presente de nitrato, arsénico, níquel, cromo, cadmio, plomo y zinc.

ResultadosLa mediana de las cifras de nitrato fue 4,2mg/l (rango<1-29,0), con similares resultados en municipios urbanos y rurales (p=0,86). Los elementos traza fueron incuantificables en el 94% de las muestras de agua municipal. Se observaron diferencias entre áreas para nitrato (p<0,001) y arsénico (p=0,03). Solo el nitrato fue cuantificable en el agua embotellada (rango 2,3-15,6mg/l).

ConclusionesLa cantidad de nitrato en el agua municipal difiere entre regiones y es menor que el límite regulatorio en todas las muestras. Los elementos traza son mayormente incuantificables tanto en el agua municipal como en la embotellada.

Nitrate and trace elements have been associated with diverse health effects. One of the main routes of human exposure is water ingestion.1 Some of these elements are naturally ubiquitous and mobile in the environment, but can accumulate in soils and water sources due to the use of fertilizers, industrial emissions and other human activities.2

Nitrate is classified as a probable human carcinogen under conditions that result in endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds.3 Arsenic, cadmium, chromium (IV) and some nickel compounds are recognized carcinogens and cause other health effects.4 Lead is neurotoxic and selenium and zinc have a likely inverse relationship with gastric, prostate and breast cancer.5 Nitrate and many trace elements are regulated in the European Union, Spain, the United States and other countries. Although zinc is not regulated, water containing > 3mg/L of zinc is not acceptable for human intake.6 Systematic and published information on levels in Spain is limited and the available data are restricted to specific areas or small study populations.

We aimed to describe levels of nitrate and trace elements in tap and bottled water in the study areas of the Spanish Multicase-Control study of Cancer (MCC-Spain). Our ultimate goal was to provide relevant information for expossure assessment to water contaminants in this population.

MethodsDesign and study areasA descriptive analysis was conducted within the framework of the MCC-Spain study, carried out in 11 Spanish provinces (table 1), with 53 urban and 14 rural municipalities (<5000 inhabitants) according to population records in 2010.

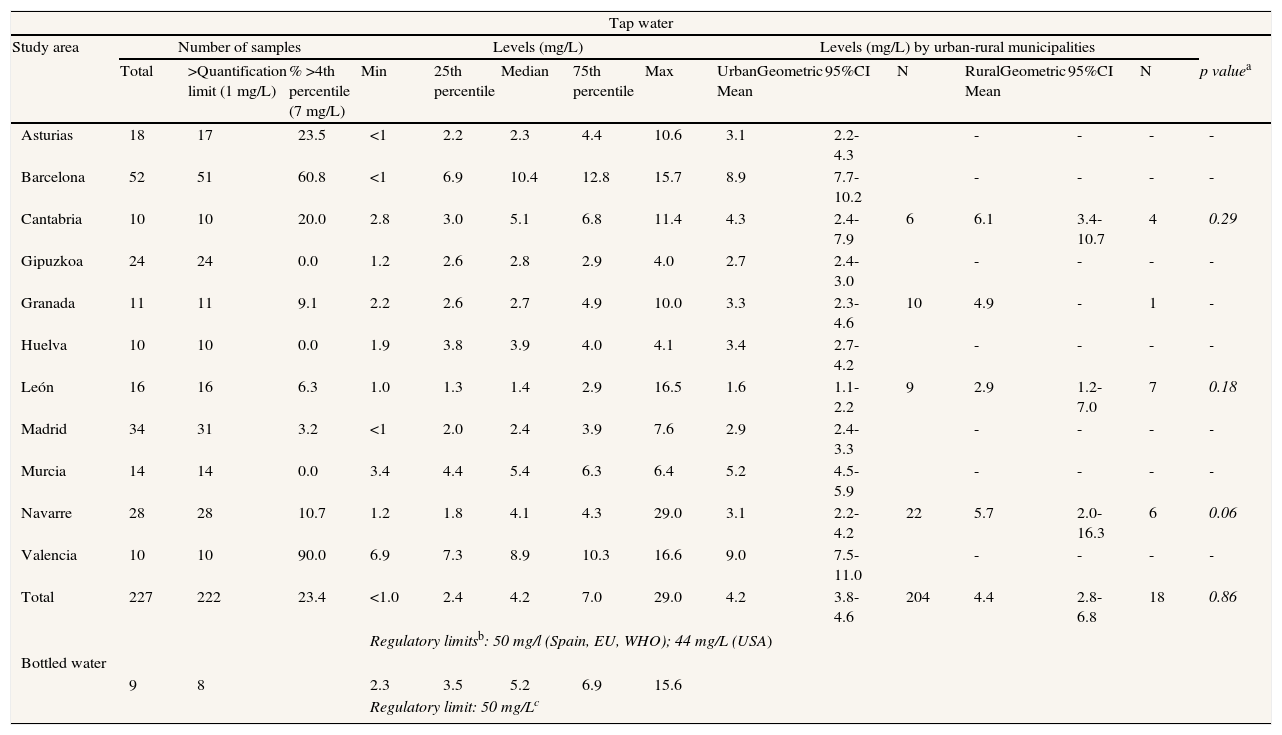

Nitrate levels in municipal and bottled water. Multi-case control study of cancer (MCC-Spain) 2010.

| Tap water | |||||||||||||||

| Study area | Number of samples | Levels (mg/L) | Levels (mg/L) by urban-rural municipalities | ||||||||||||

| Total | >Quantification limit (1 mg/L) | % >4th percentile (7 mg/L) | Min | 25th percentile | Median | 75th percentile | Max | UrbanGeometric Mean | 95%CI | N | RuralGeometric Mean | 95%CI | N | p valuea | |

| Asturias | 18 | 17 | 23.5 | <1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 10.6 | 3.1 | 2.2-4.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Barcelona | 52 | 51 | 60.8 | <1 | 6.9 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 8.9 | 7.7-10.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Cantabria | 10 | 10 | 20.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 11.4 | 4.3 | 2.4- 7.9 | 6 | 6.1 | 3.4-10.7 | 4 | 0.29 |

| Gipuzkoa | 24 | 24 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 2.4-3.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Granada | 11 | 11 | 9.1 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 2.3-4.6 | 10 | 4.9 | - | 1 | - |

| Huelva | 10 | 10 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 2.7-4.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| León | 16 | 16 | 6.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 16.5 | 1.6 | 1.1-2.2 | 9 | 2.9 | 1.2-7.0 | 7 | 0.18 |

| Madrid | 34 | 31 | 3.2 | <1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 2.4-3.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Murcia | 14 | 14 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.5-5.9 | - | - | - | - | |

| Navarre | 28 | 28 | 10.7 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 29.0 | 3.1 | 2.2-4.2 | 22 | 5.7 | 2.0-16.3 | 6 | 0.06 |

| Valencia | 10 | 10 | 90.0 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 16.6 | 9.0 | 7.5-11.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | 227 | 222 | 23.4 | <1.0 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 7.0 | 29.0 | 4.2 | 3.8-4.6 | 204 | 4.4 | 2.8-6.8 | 18 | 0.86 |

| Regulatory limitsb: 50 mg/l (Spain, EU, WHO); 44 mg/L (USA) | |||||||||||||||

| Bottled water | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | 8 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 15.6 | |||||||||

| Regulatory limit: 50 mg/Lc | |||||||||||||||

aMann-Whitney U test.bAccording to Spanish legislation (Royal Decree 140/2003), European Legislation (Directive 98/83/CE) and the World Health Organization (WHO Guidelines 2011), US Environmental Protection Agency (US Federal Register 40CFR. July 1991) equivalent to 10mg/l of nitrate- N.cAccording to Spanish legislation (Royal Decree 1074/2002).

Tap water samples were collected between March and July 2010 in 227 randomly selected locations (households and public buildings). The number of samples per area was defined according to the number of person-years included in the MCC study. Sampling procedures followed a common protocol. In January 2011, we purchased a 500mL bottle of the nine most frequently consumed brands in Spain, according to the National Association of Bottled Water Companies.

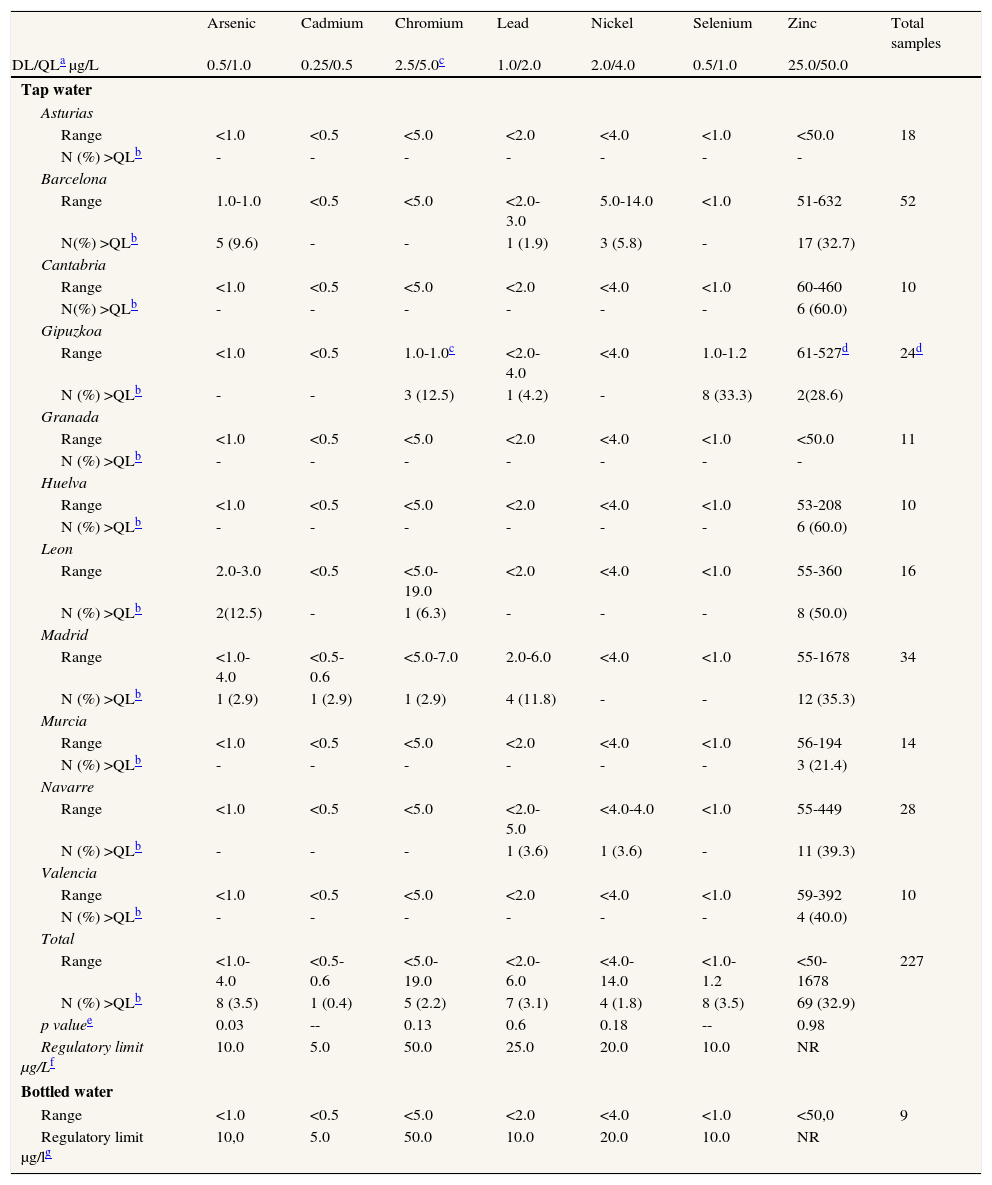

Laboratory analysisLevels of nitrate and seven trace elements (arsenic, nickel, chromium, cadmium, lead, selenium and zinc) were measured at the Public Health Laboratory of Gipuzkoa (Spain), certified by the National Accreditation Institution. Nitrate was quantified by ultraviolet spectrophotometry with 0.5/1.0mg/L detection/quantification (DL/QL) limits. Arsenic, nickel, chromium, cadmium and lead were measured by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry (GF-AAS), selenium by hydride generation (HG-AAS), and zinc by flame (F-AAS). DL/QL are detailed in table 2.

Levels of trace elements in municipal and bottled water by study area. Multi-case control study of cancer (MCC-Spain) 2010.

| Arsenic | Cadmium | Chromium | Lead | Nickel | Selenium | Zinc | Total samples | |

| DL/QLa μg/L | 0.5/1.0 | 0.25/0.5 | 2.5/5.0c | 1.0/2.0 | 2.0/4.0 | 0.5/1.0 | 25.0/50.0 | |

| Tap water | ||||||||

| Asturias | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | <50.0 | 18 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Barcelona | ||||||||

| Range | 1.0-1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0-3.0 | 5.0-14.0 | <1.0 | 51-632 | 52 |

| N(%) >QLb | 5 (9.6) | - | - | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.8) | - | 17 (32.7) | |

| Cantabria | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 60-460 | 10 |

| N(%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6 (60.0) | |

| Gipuzkoa | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | 1.0-1.0c | <2.0-4.0 | <4.0 | 1.0-1.2 | 61-527d | 24d |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | - | 8 (33.3) | 2(28.6) | |

| Granada | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | <50.0 | 11 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Huelva | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 53-208 | 10 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6 (60.0) | |

| Leon | ||||||||

| Range | 2.0-3.0 | <0.5 | <5.0-19.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 55-360 | 16 |

| N (%) >QLb | 2(12.5) | - | 1 (6.3) | - | - | - | 8 (50.0) | |

| Madrid | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0-4.0 | <0.5-0.6 | <5.0-7.0 | 2.0-6.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 55-1678 | 34 |

| N (%) >QLb | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (11.8) | - | - | 12 (35.3) | |

| Murcia | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 56-194 | 14 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (21.4) | |

| Navarre | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0-5.0 | <4.0-4.0 | <1.0 | 55-449 | 28 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) | - | 11 (39.3) | |

| Valencia | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | 59-392 | 10 |

| N (%) >QLb | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (40.0) | |

| Total | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0-4.0 | <0.5-0.6 | <5.0-19.0 | <2.0-6.0 | <4.0-14.0 | <1.0-1.2 | <50-1678 | 227 |

| N (%) >QLb | 8 (3.5) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2.2) | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) | 8 (3.5) | 69 (32.9) | |

| p valuee | 0.03 | -- | 0.13 | 0.6 | 0.18 | -- | 0.98 | |

| Regulatory limit μg/Lf | 10.0 | 5.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | NR | |

| Bottled water | ||||||||

| Range | <1.0 | <0.5 | <5.0 | <2.0 | <4.0 | <1.0 | <50,0 | 9 |

| Regulatory limit μg/lg | 10,0 | 5.0 | 50.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | NR | |

Differences between study areas were tested with the Kruskall Wallis rank test. Nitrate levels were compared between urban and rural municipalities in provinces where both types of municipality were sampled (Cantabria, Leon and Navarre) by applying the Mann Whitney U test.

ResultsNitrate was quantified in 222 tap water samples (97.8%). Median levels ranged from 1.4mg/L (Leon) to 10.4mg/L (Barcelona) and differences among study areas were significant (p<0.001). Most determinations in Valencia and Barcelona were in the highest quartile overall (> 7mg/L). Levels in rural and urban municipalities were similar (p=0.86). Nitrate was quantified in eight bottled water samples (88.9%) with a maximum level of 15.6mg/L (table 1).

On average, trace elements were below the quantification limit in 94% of tap water samples. Zinc was the most frequently quantified element (32.8%) in all areas except Granada. Arsenic was quantified in Barcelona, Leon and Madrid. Cadmium was quantified in Madrid and selenium in Gipuzkoa. Chromium was found in Gipuzkoa, Leon and Madrid. Lead was quantified in Barcelona, Gipuzkoa, Madrid and Navarre and nickel in Barcelona and Navarre. Differences among areas were significant for arsenic (p=0.03). Trace elements were unquantifiable in bottled water samples (table 2).

DiscussionNitrate and trace elements were below regulatory limits in 227 municipal water samples from 11 Spanish provinces in Spain. Trace elements were under quantification limits in 94% of the samples. Significant differences among areas were observed for nitrate and arsenic. Only nitrate was measurable in bottled water samples, at concentrations below regulatory limits.

We found similar levels of nitrate in urban and rural areas. Nitrate levels are usually higher in agricultural (rural) areas. However, in urban regions, nitrate could be produced by industrial sources, wastewater and solid waste disposal.4 In addition, water supplying urban areas could be collected in rural regions. Our study had limited power to verify urban-rural differences, because most of the study areas included only urban municipalities.

We did not find nitrate levels exceeding regulatory limits in tap water, contrary to studies in France3 and Sicily,7 where 6% of 2019 samples and 4.7% of 667 samples, respectively, exceeded this limit. Our measurements are consistent with Spanish reports from Galicia8 (0-55.4mg/L in spring water) and Tenerife (mean<10mg/L in tap water).9 Our results confirm that nitrate levels differ geographically, which could be explained by several environmental factors such as water source (ground vs. surface), land use and soil characteristics, among others.1

Arsenic values were below the quantification limit in 96.5% of tap water samples, differing from Spanish reports of levels exceeding the regulatory limits (10μg/L) in Madrid10, Leon11 and Caldes de Malavella.12 The available literature shows wide variability among regions, due to natural geologic characteristics and anthropogenic sources of contamination.

Even the maximum zinc levels measured in Madrid (≈1.7mg/L) did not exceed the recommended limit to avoid toxic effects (3mg/L) and were similar to results from Finland (1.1mg/L).6 Higher concentrations of zinc, lead, chromium, nickel, cooper and iron could be observed due to release from piping and fittings. According to a study performed in the Basque country,13 this contaminant pathway is not important in Spain, which could explain the low levels found of nickel and other trace elements. Selenium was mainly unquantifiable, probably because most of the chemical forms remain fixed to soils and do not reach drinking water. Further research is needed to understand the major environmental determinants of trace element levels in drinking water, given their potential effects, possibly protective, on some cancers.5

Nitrate levels in bottled water were similar to those reported in Tenerife (range 0.4-12mg/L)10 and other European bottled waters (means from <0.04 to 18.1mg/L) analyzed in a Canadian study14 but were higher than those found in Germany (median 1.08mg/L).15 Studies from the United States and Germany15 found arsenic, cadmium, zinc, selenium and nickel exceeding regulatory levels, but our results, mostly below the regulatory limits, were also verified in other countries.

We provide broader information than that found in previous Spanish reports on water contaminants. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first study measuring various trace elements in Spanish bottled water. Since nitrate levels in drinking water were under regulatory limits, specific recommendations about water intake are not warranted. Some implications for exposure assessment are the following: 1) geographical variability in nitrate levels should be taken into account; 2) drinking water does not appear to be an important source of exposure to trace elements in the study areas; and 3) the contribution of bottled water intake to nitrate exposure, so far considered insignificant, needs further analysis.

In conclusion, nitrate levels differ significantly among Spanish regions but are always under the regulatory limits. Trace element levels are low and are mainly unquantifiable in tap and bottled water. This information is helpful to evaluate exposure and the association of these contaminants with prevalent tumors in the Spanish population.

Nitrate and trace elements in drinking water have been associated with adverse health effects, including cancer, but the evidence on some of these chemicals is still inconclusive. The available information on exposure levels in Spain is restricted to specific areas or small study populations.

What does this study add to the literature?We conducted systematic sampling in a large study area in Spain (67 municipalities in 11 provinces). Nitrate levels in municipal drinking water differed among regions and were under the maximum regulatory limits. Bottled water also contained low nitrate levels. Most trace elements were unquantifiable in drinking water (both tap and bottled water). Our results are useful to evaluate exposure levels in Spain.

N. Espejo-Herrera performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript under the supervision of C.M. Villanueva. E. Ulibarrena performed the laboratory analysis. All the authors participated in the study design, data collection, review and interpretation of the results. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all the authors. All members of the Water Working Group of the MCC-Spain study, listed as co-authors in the Annex, contributed to data collection, water sampling in the study areas and reviewed the results of the study.

FundingThis study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER (PI08/0533, PI08/1770, PI08/1359, PI09/1662), FIS PI09/00773, Acción Transversal del Cáncer del Consejo de Ministros del 11/10/2007 and the CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública.

Competing interestsNone.

We thank Remedios Pérez and José Luis Rodrigo (Public Health Institute of Navarre) for their contributions.

Co-authors: Glòria Carrasco-Turigas, Esther Gràcia-Lavedán, Ana Espinosa (Center for Research in Environmental Epidemiology, CREAL, Barcelona); Victor Moreno (Catalan Institute of Oncology, ICO, Barcelona; Biomedical Research Institute, IDIBELL; University of Barcelona, UB); Laura Costas (Catalan Institute of Oncology, ICO, Barcelona); Marina Pollán, Pablo Fernández Navarro, Javier García, Esther García-Esquinas (Cancer and Environmental Epidemiology Unit, National Center for Epidemiology, Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid); Margarita Palau (National Information System for Drinking Water, SINAC); Estefanía Toledo (Public Health Institute of Navarra; Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Navarre, Pamplona); Jone M. Altzibar, Itziar Zaldua (Public Health Division of Gipuzkoa); Vicente Martín (University of León); Juan Alguacil (Center for Research in Environment and Health, CYSMA, University of Huelva); and Rosana Peiró (Center for Research in Public Health, CSISP, Valencia), as members of the MCC-Spain Water Working Group.