Given that lifestyleshave similar determinants and that school-based interventions are usually targeted at all the risks that affect adolescents, the objective of this systematic review was to summarize the characteristics and effects of school-based interventions acting on different behavioral domains of adolescent health promotion.

MethodsThe review process was conducted by two independent reviewers who searched PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and ERIC databases for experimental or observational studies with at least two measures of results published from 2007 to 2011, given that the research information available doubles every 5 years. Methodological quality was assessed with a standardized tool.

ResultsInformation was extracted from 35 studies aiming to prevent risk behaviors and promote healthy nutrition, physical activity, and mental and holistic health. Activities were based on theoretical models and were classified into interactive lessons, peer mediation, environmental changes, parents’ and community activities, and tailored messages by computer-assisted training or other resources, usually including multiple components. In some cases, we identified some moderate to large, short- and long-term effects on behavioral and intermediate variable.

ConclusionsThis exhaustive review found that well-implemented interventions can promote adolescent health. These findings are consistent with recent reviews. Implications for practice, public health, and research are discussed.

Dado que los estilos de vida tienen similares determinantes, y las intervenciones escolares suelen estar dirigidas a todos los riesgos que aparecen durante la adolescencia, el objetivo de esta revisión sistemática ha sido resumir las características y los efectos de intervenciones escolares de promoción de la salud dirigidas a diferentes áreas de conducta.

MétodosLa revisión se realizó por dos evaluadores que independientemente realizaron una búsqueda en las bases de datos PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, y ERIC, de estudios observacionales y experimentales con al menos dos medidas de resultados, publicados entre 2007 y 2011, pues la información científica disponible se duplica cada cinco años. La calidad metodológica se evaluó con herramientas estandarizadas.

ResultadosSe recogió información de 35 estudios dirigidos a promover la nutrición saludable y la actividad física, promover la salud mental y holística,y prevenir conductas de riesgo. Las actividades se basaron en distintos modelos teóricos y se calificaron en lecciones interactivas, mediación por pares, cambios ambientales, actividades con padres y comunidad, atención “a medida” asistida por el ordenador u otros recursos, con frecuencia incluyeron múltiples componentes. En algunos casos, se encontraron de moderado a largos efectos, a corto y largo plazo sobre variables comportamentales e intermedias.

ConclusionesLa fortaleza de esta revisión es que se ha llevado a cabo de modo exhaustivo, y apunta a que intervenciones bien implementadas pueden promover la salud adolescente. Los hallazgos son consistentes con revisiones recientes, y sus implicaciones para la práctica, la salud pública, y la investigación han sido discutidos.

Bio-psycho-social changes may lead to unhealthy lifestyles in adolescence, which tend to co-occur and have similar determinants. This has a major impact in terms of disease, disability, death, and high costs to families and community.1,2

Adolescence has been associated to unhealthy nutrition and physical activity is reduced in this period.3 Obesity is linked to body image disorders that affect mental health and well-being.4 In 2010 the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) international study found that 14.3% of participants were overweight. The cited study also found that 19% of 15 year-old's reported smoking at least once a week, 26% a prevalence of weekly alcohol consumption, 33% having been drunk twice or more, and 18% using cannabis at least once in life. Regarding sexuality, 27% of 15 year-old's reported having had sexual intercourse.1 In addition, traffic injury is the leading cause of death among 15-19 year-old's and among 10–14 year old's.5

In order to prevent unhealthy lifestyles health promotion programmes are performed at schools. These are appropriate contexts to improve public health that allow access to higher numbers of adolescents.6,7 Systematic reviews have been performed to evaluate the effect of school-based interventions regarding nutrition and physical activity,6,8 substance use,9,10 or violence,11 which found some positive effects of variable magnitude. Peters and cols performed a review on three domains, i. e., nutrition, substance use and sexuality.7

This is a systematic review across different behavioural domains since they have similar determinants, and school-based interventions usually deal with all risks that affect adolescence. We questioned ¿What are the main characteristics of recent school-based health promotion and risk prevention interventions targeted to adolescents? ¿What are their main effects? The objective was to summarize characteristics and effects of school-based interventions leading to behaviours such as nutrition, physical activity, mental and holistic health, and risk prevention (eating disorders, substance use, sexuality, violence and road safety).

MethodsIn February 2012 a search was performed in PubMed, PsycINFO, ERIC and Scopus, for both review and original articles. Revised databases include relevant information on health, psychology, education and multidisciplinary sciences. Since research information is updated every five years and previous works become obsolete,12,13 we considered articles published from 2007.01.01 to 2011.12.31.

The following search terms: adolescent, program evaluation, health promotion, and whenever it was possible the thesaurus tool were used (complementary material: table I). We considered getting in touch with authors if there were doubts or difficulty in retrieving full-text.

Reference lists of both original and meta-analytic articles selected were verified to identify additional studies which reached inclusion criteria. These were English, Spanish, and Portuguese languages, with abstract, quantitative experimental or observational studies in which an intervention group was compared at least twice (pretest and posttest), interventions aimed at healthy adolescents (11-17 years) without specific illness or risks (such as substance consumers, mental disorders or obese), the primary interventions were conducted at school, and the article had a moderate to strong score in quality assessment.

In the final sample, exclusion criteria were different to original and had weak quality scores. The standardized quality assessment tool of Effective Public Health Practice Project was used.14 Eight components were scored (weak/moderate/strong): (1) Selection bias, (2) study design, (3) confounders, (4) blinding, (5) data collection, (6) withdrawals and drop-outs, (7) intervention integrity, and (8) analysis.

When there were multiple publications for the same study a project account was created. The most important information was extracted and summarized in tables attending the following categories: health nutrition and physical activity, mental and holistic health, and risk prevention interventions. Regarding the sustainability, we considered population and setting, whether outcomes were measured over multiple time points and at short or long-term. Regarding the applicability we also reviewed if effect varied across different populations and settings.15 Whenever it was possible, the following subcategories were identified: reference (author, year), study characteristics (design, randomized level, country, population, follow-ups, number of variables, participants’ age), intervention characteristics (setting, objectives, theoretical framework, implementation characteristics), main effects (only those that p<.05). When it was possible, Cohen's d was calculated.16 We considered 0.2 low, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large effect. When offered, we used odds ratio (1.50 low, 3.50 moderate, 9.00 large effect), and R2 (0.01 low, 0.06 moderate, 0.14 large effect).17 However, given the heterogeneity of studies regarding interventions, participants, outcome measures, no pooled effect sizes were calculated but a narrative systematic review was performed.

Two independent reviewers were involved in every step, i. e., screening the results from database searches, carrying out quality assessment, extracting data, reviewing drafts and the final report. Disagreements were solved by discussion. Standardized tools were adapted and used independently.6

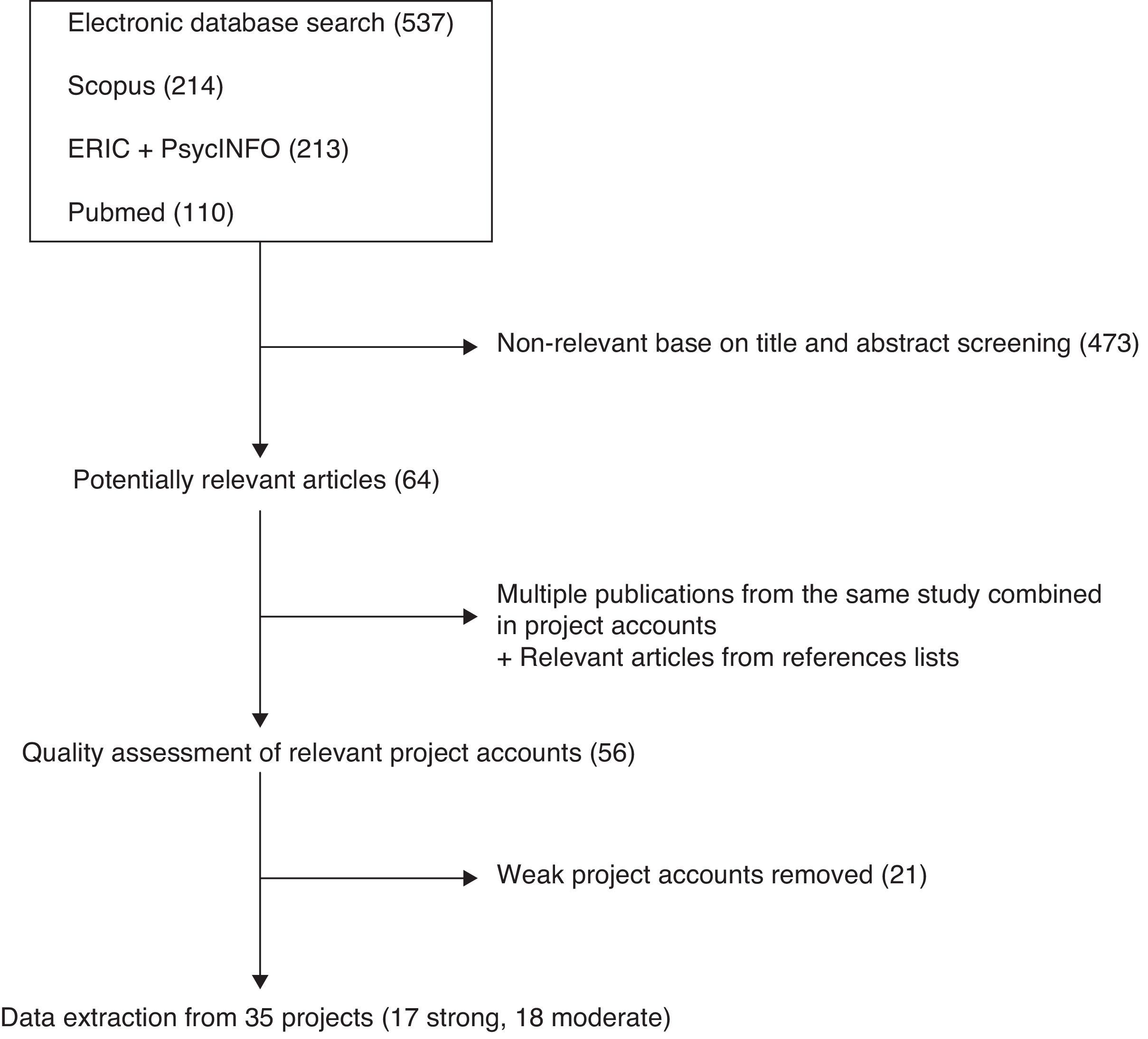

ResultsLiterature search, quality rating, and characteristics of studies537 abstracts were identified. Subsequently, 64 full-text articles were retrieved (Fig. 1), and finally, 56 projects were selected. The reasons for exclusion were: participants were not 11 to 17 years-old, interventions were not primary based on school, were aimed to illness or in risk adolescents, result measures were not shown, or there was only one measure.

The quality of the 56 projects was evaluated and 21 weak ones were excluded. The main limitations were small sample size that was inadequately explained, no control for potentially confounders, no binding, high percentage of drop-outs, and no reliable instruments.

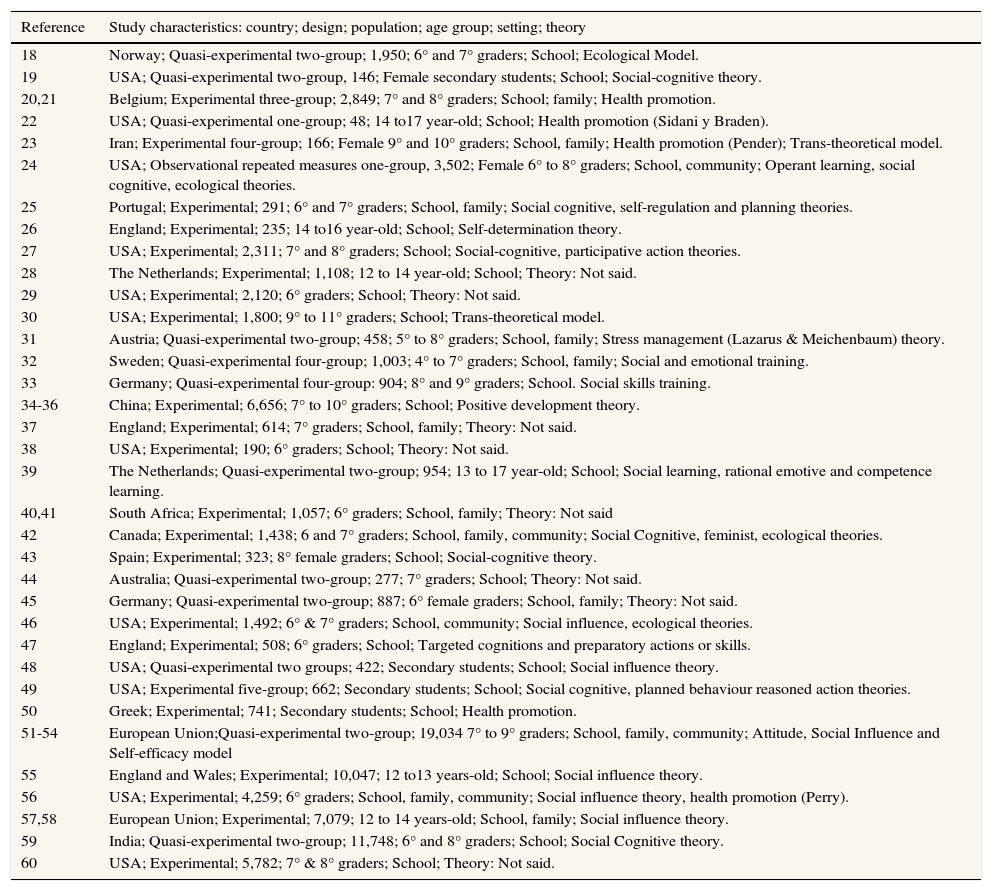

Finally, data were extracted from 35 projects (Table 1); they were classified into three categories. Thus 12 aimed at nutrition and physical activity; eight at mental and holistic health; and 15 at prevent risk behaviours (supplementary material: Tables II to IV).

Contributions about effectiveness evaluation of school health promotion programs.

| Reference | Study characteristics: country; design; population; age group; setting; theory |

|---|---|

| 18 | Norway; Quasi-experimental two-group; 1,950; 6° and 7° graders; School; Ecological Model. |

| 19 | USA; Quasi-experimental two-group, 146; Female secondary students; School; Social-cognitive theory. |

| 20,21 | Belgium; Experimental three-group; 2,849; 7° and 8° graders; School; family; Health promotion. |

| 22 | USA; Quasi-experimental one-group; 48; 14 to17 year-old; School; Health promotion (Sidani y Braden). |

| 23 | Iran; Experimental four-group; 166; Female 9° and 10° graders; School, family; Health promotion (Pender); Trans-theoretical model. |

| 24 | USA; Observational repeated measures one-group, 3,502; Female 6° to 8° graders; School, community; Operant learning, social cognitive, ecological theories. |

| 25 | Portugal; Experimental; 291; 6° and 7° graders; School, family; Social cognitive, self-regulation and planning theories. |

| 26 | England; Experimental; 235; 14 to16 year-old; School; Self-determination theory. |

| 27 | USA; Experimental; 2,311; 7° and 8° graders; School; Social-cognitive, participative action theories. |

| 28 | The Netherlands; Experimental; 1,108; 12 to 14 year-old; School; Theory: Not said. |

| 29 | USA; Experimental; 2,120; 6° graders; School; Theory: Not said. |

| 30 | USA; Experimental; 1,800; 9° to 11° graders; School; Trans-theoretical model. |

| 31 | Austria; Quasi-experimental two-group; 458; 5° to 8° graders; School, family; Stress management (Lazarus & Meichenbaum) theory. |

| 32 | Sweden; Quasi-experimental four-group; 1,003; 4° to 7° graders; School, family; Social and emotional training. |

| 33 | Germany; Quasi-experimental four-group: 904; 8° and 9° graders; School. Social skills training. |

| 34-36 | China; Experimental; 6,656; 7° to 10° graders; School; Positive development theory. |

| 37 | England; Experimental; 614; 7° graders; School, family; Theory: Not said. |

| 38 | USA; Experimental; 190; 6° graders; School; Theory: Not said. |

| 39 | The Netherlands; Quasi-experimental two-group; 954; 13 to 17 year-old; School; Social learning, rational emotive and competence learning. |

| 40,41 | South Africa; Experimental; 1,057; 6° graders; School, family; Theory: Not said |

| 42 | Canada; Experimental; 1,438; 6 and 7° graders; School, family, community; Social Cognitive, feminist, ecological theories. |

| 43 | Spain; Experimental; 323; 8° female graders; School; Social-cognitive theory. |

| 44 | Australia; Quasi-experimental two-group; 277; 7° graders; School; Theory: Not said. |

| 45 | Germany; Quasi-experimental two-group; 887; 6° female graders; School, family; Theory: Not said. |

| 46 | USA; Experimental; 1,492; 6° & 7° graders; School, community; Social influence, ecological theories. |

| 47 | England; Experimental; 508; 6° graders; School; Targeted cognitions and preparatory actions or skills. |

| 48 | USA; Quasi-experimental two groups; 422; Secondary students; School; Social influence theory. |

| 49 | USA; Experimental five-group; 662; Secondary students; School; Social cognitive, planned behaviour reasoned action theories. |

| 50 | Greek; Experimental; 741; Secondary students; School; Health promotion. |

| 51-54 | European Union;Quasi-experimental two-group; 19,034 7° to 9° graders; School, family, community; Attitude, Social Influence and Self-efficacy model |

| 55 | England and Wales; Experimental; 10,047; 12 to13 years-old; School; Social influence theory. |

| 56 | USA; Experimental; 4,259; 6° graders; School, family, community; Social influence theory, health promotion (Perry). |

| 57,58 | European Union; Experimental; 7,079; 12 to 14 years-old; School, family; Social influence theory. |

| 59 | India; Quasi-experimental two-group; 11,748; 6° and 8° graders; School; Social Cognitive theory. |

| 60 | USA; Experimental; 5,782; 7° & 8° graders; School; Theory: Not said. |

The projects were manly conducted in Europe (N=17), and the United States (USA) (N=12). The participants were around 13 mean of age. Specifically, four studies were orientated to female students, two to rural communities, and two to Afro-American students.

The majority were experimental (N=24) or quasi-experimental (N=10), where one experimental group (EG) was compared to a control group (CG) that delivered its habitual curriculum (N=28). In addition, two studies applied qualitative methodology in order to complement quantitative results.

In six projects two measures were carried out, although Shek and cols34 delivered posttest measures after two years of intervention. 15 projects had three measures, in 12 of them were delivered in short-term (10 weeks to 12 months), while in the rest in long-term (mostly two years). Nine projects had more measures, where the latest was carried in long term (two/three-year follow-up). Population size was very variable between 48 participants22 and 11,748 participants55 at pretest.

Characteristics of school-based interventions.

All interventions had as main focus students at schools, some of them were also performed in other contexts such as family (N=11),20,21,23,25,31,32,39–42,51–54,56–58 and community (N=5).24,42,46,51–54,56

The majority were based on theoretical models of behaviour change (N=24), i.e., social cognitive theory,19,24,25,27,40–43,49,51–54,58 trans-theoretical model,23,30,51–54 theory of planned behaviour,39–41,51–54 self-regulation and planning theory,25 self-determination theory,26 health promotion (Sidani and Braden's, Pender's, Perry's models),20–23,50,56 social influence models,46,48,51–54 ecological models,18,24,42,46 psycho-social training,33,33,39,42 or positive youth development,34,36 among others.

The activities were implemented into six areas, i.e., interactive lessons, peer mediation, improving accessibility by environment changes, activities with parents, activities with community, and tailored message by computer-assisted training or other resources.

The majority (N=21) performed interactive lessons of variable length, i.e., from two lessons in total42 to one lesson per week over the year.32The mean was 10 lessons. These were performed mainly in the classroom by professors or previously trained health practitioners (from 1-day to 5-day training). In Jemmot III and cols, the lessons were delivered during afterschool by community co-facilitator that received 2.5-day to 8-day training.40,41,49

Scarce information was given about types of interactive methodologies, but in some projects discussion, consensus, role-play, modeling, solving problems, training in decision-making process, games or film analysis were named. In addition, some projects added physical training to interactive lessons.19,22–25,28,41

Peer mediation conducted by previously trained peer leaders was carried out in 11 projects, mainly those for preventing risk behaviour such as eating disorder,42 HIV/AIDS prevention,48 substance use,51–59 and peer violence.46 They gave information both formally,29 and informally.51–57 In McVey and cols,42 support groups conducted by a nurse were performed. Dzewaltowski and cols27 and Bonell and cols37 used action teams that led environment changes such as school policy and community activities. In Bonell and cols37 these teams also involved school personal and parents. Some interventions performed media campaigns by peers such as music records,48 or media announcements.46

Environment changes were performed in the majority of physical activity and health nutrition interventions to improve accessibility, increasing hours of physical training, changing meals at school cafeterias, or giving vegetables and fruits, among others.18,20,21,24,27,28

Some projects carried out activities with parents (N=11) and communities (N=5). The parents’ activities were based on homework with students,31,32,40,41,51–54,56 and parents’ lessons or information with variable participation.20,21,25,42,57,58 In Taymoory y cols,23 students and their parents were proposed to do exercise outside. Community activities involved organizing workshops, events or services, mass media information or attending activities performed by community members.24,42,46,51–54,56

Some interventions were focus in tailored message, such as leaflets,47 computer-tailored training,20,21,33 and others performed on-line lessons.33,38,60

Regarding applicability, five interventions were based on programs previously evaluated in other contexts. For instance, Hampel and cols,31 carried out an intervention previously performed in a clinical environment; Richardson and cols44 adapted an intervention from a community context in United Kingdom to schools in Australia; Jemmot and cols40,41,49 performed a similar intervention in different contexts (USA African-American and South-African students) but did not compare these; Komro56 and cols adapted an intervention from a rural to an urban environment; and Campbel55 and cols adapted an intervention targeted to sexual health to a smoking prevention domain. Subsequently, Sheck y cols34–36 and Wick y cols45 performed dissemination studies to evaluate interventions previously piloted in real-settings. Finally, Germeni y cols50 and De Vries and cols51–54 performed their interventions in different settings. Germeni y cols50 carried out theirs in three types of schools (public, private and vocational) and found that effect was more favourable at vocational and public schools than at private schools. De Vries and cols51–54 performed their intervention in different countries, and found some differences in outcomes regarding the country of origin.

Main effectsSignificant effects (p<0.05) are shown in supplementary material (tables II to IV). The majority of interventions aimed at promoting health nutrition and physical activity found moderate to large effects such as Dunton and cols on physical activity (d=0.58),19 Haerens and cols on physical activity of light intensity (d=0.54) and percent of energy from fat (in girls) (d=1.56),20,21 Covelli on physical activity (d=2.32), fruit and vegetable consumption (d=2.82), and knowledge (d=4.37),22 Taymoori and cols on all measures of physical activity (R2=0.29-0.34) in posttest, and in physical activity minutes per week (d=0.59) in follow-up,23 Chatzisarantis&Hagger on intentions (d=0.73), and physical activity (R2=0.22),26 Dzewaltowski and cols on physical activity (d=1.24-1.88), self-efficacy (d=1.47-3.25) and school support (d=2.29),27 and Forneris and cols on physical activity self-efficacy (d=1.86-3,16) and knowledge (d=1.92-2.37).29

Some mental and holistic health promotion interventions found moderate to large effects such as Hampel and cols on stress coping (R2=0.73),31 Fridrici&Lohaus on stress knowledge and coping (R2=0.10),33 Shek and cols on one indicator of positive development (d=1.57),34–36 and Jemmott III and cols on knowledge (d=1.03), attitude (d=0.89) and intention (d=0.81) to health promotion.40,41 Those that measured behaviours found low effects.32,40,41 In two projects results from qualitative methodology pointed to reduce risk behaviours.34–37 Finally, some interventions aimed at preventing risk behaviours found moderate to large effects such as McVey and cols on internalization of media ideals (d=0.73), body satisfaction (d=0.81), disordered eating attitude and behaviour (d=1.05) in risk groups,42 Raich and cols on nutrition, eating attitudes and knowledge (R2=0.06) in adolescents with early menarche,43 Richardson and cols on media literacy (d=0.95),44 Swaim& Kelly on violent intentions against peers (d=0.98), physical assault (d=3.29), verbal victimization (d=2.90), and perceived school safety (d=4.04),46 Lemieux and cols on attitude (R2=0.33), and social normative support for abstinence (in girls, R2=0.24) in HIV/AIDS prevention,48 Hills & Abraham on intentions (d=0.98), self-efficacy condom availability (d=0.71-1.82), purchased (d=0.59) and carried condoms (d=0.62),47 De Vries and cols on tobacco use (d=0.06-0.08),51–54 and Perry and cols on intermediate variables of tobacco use (d=2.80-13.5).59

DiscussionWe have found good-quality projects in physical activity, health nutrition, mental and holistic health, and risk behaviour prevention. Implementation activities were performed in six areas, which were classified in interactive lessons, peer mediation, improving accessibility by environment changes, activities with parents, with community, and tailored message; and they mainly addressed facilitors and barriers, social influences (peers, family, school, media and community), cognitive, emotional and behavioural skills, and including multiple components. Similar activities and behavioural determinants were approached in interventions that led to different behaviours, this point that integrative programs addressing multiple behaviours could be implemented in schools by using those effective activities and elements.7 In addition, the majority of projects were based on theoretical models; previous authors emphasized that theory-based programs produce better effects.6,7,15

Some projects found moderate to large short and long-term effect and some of them measured outcomes over multiple time points. Most projects were carried out in “real conditions”, in a wide number of schools with large samples, and in some cases included family and community contexts, these situations contribute to sustainability of interventions.15

The majority of the projects conducted to promote physical activity and health nutrition found moderate to large effects on behavioural variables. Most of them were based on health promotion models, but effects were found in short to medium-term such as Haerens and cols that performed environment changes plus tailored-computer training and activities with parents,20,21 Dunton and cols19 and Covelli22 that carried out interactive lessons plus physical activity training, or Chatzisarantis& Hagger26 that changed the teaching style of physical education teachers to provided autonomy (feedback, rationale, sense of choice and acknowledge difficulties) for physical activity. However, Dzewaltowski and cols’ intervention found large long-term effects (two years). This was based on social cognitive theory and action teams improved accessibility to physical activity by school-environment changes.27

Subsequently, a few projects aimed at mental and holistic health found large effects. Some of them in a short-term, such as Hampel and cols, in stress prevention, that performed interactive lessons and activities with parents,31 and Jemmott III and cols, which based on social-cognitive and planned behaviour theories, carried out lessons taught by community co-facilitators.40,41 Likewise, Shek and cols that performed interactive lessons found effect on positive development after two years.34–36 Finally, some projects intended for risk prevention found large effects, we emphasize those in long-term. For instance, in smoking prevention, De Vries and cols, who based on social influences theory, performed active lessons combined with activities with peers, parents, and community,51–54 Perry and cols, who based on social cognitive theory, carried out interactive lessons, peer mediation, school events, and parent information.59 In violence prevention, Swaim& Kelly performed activities at school and community led by peers, based on social influence theory and ecological model.46

Regarding applicability, although most interventions were performed in a wide number of schools with large populations, only two studies compared an intervention in different contexts. De Vries and cols51–54, compared their program in different countries across Europe and found some disparity effects that were explained by administrative difficulties, design limitations (regarding response rates or random assignment), and although it was based on core objectives and methods many differences appeared amongst countries.51 Germeni y cols50 also found some disparity effect across school types that were explained by the characteristics of the population, and other school-related factors.

Our review points to well-implemented programs that may promote healthy lifestyles in adolescence. Results are consistent with those reported in recent reviews;6–11 and since risk behaviours have similar determinants, the strength of this article is the review has been conducted across different behavioural domains that affect adolescence and are usually addressed in school-based interventions. In this respect, practitioners and researchers in health and education can use those elements that were effective, especially those similar across domains, in delivering health promotion interventions.7

Regarding limitations, although databases included were relevant with the interventions analyzed, we limited the search to four databases, and also limited the time period (over last five years) and languages, so some articles might be missed. The heterogeneity concerning differences in interventions, study designs, methodologies and variables used to outcome measures precludes giving a synthesis of results and performing a meta-analysis. In the future, it could be interesting to generate sub-groups or intervention types to solve this limitation. Furthermore, although we have included some aspects related to sustainability and applicability, first it was not easy identifying aspects regarding these criteria in all the projects, second our study was mainly oriented to summarize characteristics and effects including interventions. However, in the future it may be pertinent to analyze these criteria thoroughly.15

ConclusionsThis review has some implications for practice and research. Since school-based interventions are associated with some positive effects, should be continued and encouraged by public health institutes; and health promotion contents would be included more frequently in student curriculums.6There is enough evidence to encourage delivering school-based interventions based on theories about behavioural change o health promotion. There is some evidence that encourages performing interventions that promote environmental changes, dealing with social influence and improving cognitive, emotional and behavioural skills. Since the fact that similar domains were found in the areas reviewed, it would be interesting performing integrative interventions aimed at whole risks that affect adolescence. On the other hand, assisted computer and on-line intervention must be studied more.

There are many gaps in the literature that may be researched. It is necessary to find out which the main variables are that influence behavioural change in order to develop health promotion programs to intervene in said variables. It is required both to implement and evaluate (process and effect) interventions that include named evidence in a comprehensive way, and participatory action research may be useful in this kind of research. Thus, since it is very important to promote health and prevent risk in adolescence, it is necessary to take notice of research related to school-based intervention as a major priority and recognize the need to fund projects in this research field.

Editor in charge of the articleMª Felicitas Domínguez-Berjón.

Health promotion programs are performed at schools to prevent unhealthy lifestyles in Adolescence. Different systematic reviews have been carried out to evaluate the effect of school health promotion programs regarding different domains, which found some positive effects of variable magnitude.

What does this study add to the literature?This is a comprehensive systematic review across different behaviour domains since they have similar determinants, and school-based interventions deal with whole risk that affects adolescence.

We showed the main effects of interventions regarding to physical activity, nutrition, mental and holistic health, and risk behaviours. It points to well-implemented programmes may reduce risks in adolescence.

We declare that both authorshave made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) the final approval of the version to be submitted.

FundingThere is not funding.

Conflict of interestWe have not conflict of interest