This study investigates the health effects of loneliness among adults (18+ years) and elderly adults (60+ years).

MethodUsing data from the Health Survey of Catalonia (ESCA), 2013-2019, the effects of loneliness on health and healthcare utilization outcomes are estimated. Ordinary least squares estimates are provided to explore the channels affecting such relationships.

ResultsLoneliness is significantly associated to worse health outcomes in all age groups. Among adults, it reduces self-perceived health by 7.1%, increases multi-morbidities by 22.1%, and raises the probability of depression and anxiety by 65.8%. Consequently, a positive and strong association between suffering from loneliness and the use of healthcare resources is documented: with a 7.4% rise in medication use, 20.9% more emergency care visits, and 6.1% higher primary care use. Results for the elderly are aligned with adults, although the magnitude associated to self-perceived health is substantially greater (13.2%). Channels exploration identifies living alone (with a 97.3% increase) and poor household habitability (33.5% increase) as key predictors in all the analysis. Being foreign (60.3% increase in the adult population and 106% in the elderly population) and gender (women, 26.8% for the adult population and 27.5% in the elderly population) become relevant factors explaining loneliness.

ConclusionsThis study documents the impact of loneliness in Catalonia. Loneliness is associated to significant worse health and more use of healthcare. Tackling individuals with higher risk factors for loneliness could help preventing its concerning consequences on health and healthcare system.

Este estudio investiga los efectos de la soledad en la salud de adultos (+18 años) y mayores (+60 años).

MétodoUtilizando datos de la Encuesta de Salud de Cataluña, 2013-2019, se han estimado los efectos de la soledad en la salud y el uso de servicios sanitarios, proporcionando estimaciones de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para explorar los mecanismos que influyen en estas relaciones.

ResultadosLa soledad se asocia significativamente con peor salud en todos los grupos de edad. En los adultos reduce la percepción de salud un 7,1%, aumenta la comorbilidad un 22,1% y eleva la probabilidad de prevalencia de depresión y ansiedad un 65,8%. Tiene asociación positiva con el uso de recursos sanitarios: un aumento del 7,4% en el uso de medicamentos, un 20,9% más visitas a urgencias y un 6,1% más visitas en atención primaria. Los resultados para los mayores son concordantes con los de los adultos, aunque la magnitud asociada a la percepción de salud es sustancialmente mayor (13,2%). La exploración de mecanismos identifica vivir solo (con un aumento del 97,3%) y la mala habitabilidad del hogar (33,5% de aumento) como predictores clave en todos los análisis. Ser extranjero (60,3% en los adultos y 106% en las personas mayores) y el sexo (mujer, 26,8% y 27,5%) son otros factores relevantes que explican la soledad.

ConclusionesSe documenta el impacto de la soledad en Cataluña, encontrando una salud significativamente peor y un mayor uso de servicios sanitarios. Abordar a los individuos con mayores factores de riesgo podría ayudar a prevenir estos riesgos.

Loneliness has become an increasingly significant public health issue, driven by profound demographic and societal changes.1 Loneliness is a subjective emotional state characterized by feelings of isolation, disconnection, and lack of belonging, while social isolation refers to the objective condition of limited social interactions. Public health literature frequently examines them together under the term “social isolation and loneliness” (SIL) due to their shared determinants and overlapping consequences.2,3 Quantifying loneliness remains challenging due to its subjective nature, yet validated tools such as the Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3)4 and the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS)5 are commonly employed to assess social connection indirectly.

In Spain, one in five individuals suffers from loneliness (2024), with 13.4% suffering from chronic loneliness —persisting for 2 or more years.6 The prevalence of loneliness differs by age and gender. For age, the highest levels have been identified among the elderly (+65) (17.5%, reaching 20% for +75) and young adults (aged 18-to-24 years old), where a peak of 35% is identified. These figures may underestimate loneliness among the most vulnerable elderly group: institutionalised individuals and those with major long-term care needs. For gender, literature points to the idea that women report more loneliness than men do across various age groups and cultures.7 In Spain, 21.8% of women report loneliness compared to 18.0% of men.6

Health implications of SIL are profound and well documented.1 Loneliness is strongly associated with a heightened risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cognitive decline, dementia, and premature all-cause mortality.8–11 From a psychological perspective, is a contributor to depression and emotional distress. Prolonged isolation undermines mental resilience, leading to increased risks of anxiety, cognitive impairments, and deteriorating psychological well-being.12,13 Hence, SIL is associated to higher healthcare utilization,14,15 but remains an under-prioritized issue in public health.16

Demographic and social changes contribute to rising loneliness. Advances in healthcare and living standards have increased life expectancy (85.8 and 80.3 years for Spanish women and men),17 at the expense of higher mobility restrictions and sensory impairments.18 The loss of autonomy in activities of daily living (ADL) intensifies feelings of isolation and dependency, compounding the adverse effects of loneliness.10,19 Similarly, living arrangements have also affected SIL: decreasing marriage rates, rising rates of separation and lower fertility have altered family dynamics, leading to fewer opportunities for multigenerational living and caregiving.20,21 These changes have diminished traditional sources of support, increasing the risks of SIL and reducing the protection offered by marriage.22 Indeed, living alone has been identified as a significant predictor of loneliness, particularly among older adults.18

Other social indicators —associated with vulnerable populations— have also been associated with greater incidence of loneliness. Older migrants experience heightened loneliness due to cultural barriers and reduced access to supporting networks.23–25 Additionally, lower economic status is strongly associated with SIL.26–28 These factors also explain non-negligible rates of loneliness among young-to-adult cohorts.6

The study investigates the impact of loneliness on health outcomes and healthcare utilization in Catalonia, using data from the Health Survey of Catalonia (ESCA). The findings suggest that loneliness is associated with worse physical and mental health, regardless of the type of measures (objective vs subjective). In turn, this leads to higher utilisation of healthcare. The paper contributes to the literature on the effects of SIL documenting the effects in Catalonia in a range of effects and providing differentiated effects by age.

Understanding the channels through which loneliness emerges is essential to mitigate and design protective policies. With this aim, the paper explores the channels leading to loneliness. This adds to the literature by identifying that commonly recognized drivers, such as age and lack of autonomy, become less determinant if we control for socioeconomic factors, like living alone, economic deprivation and migrant status.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: section 2 explains the data and the methodology; section 3 presents the results, which are discussed in section 4; finally, section 5 concludes.

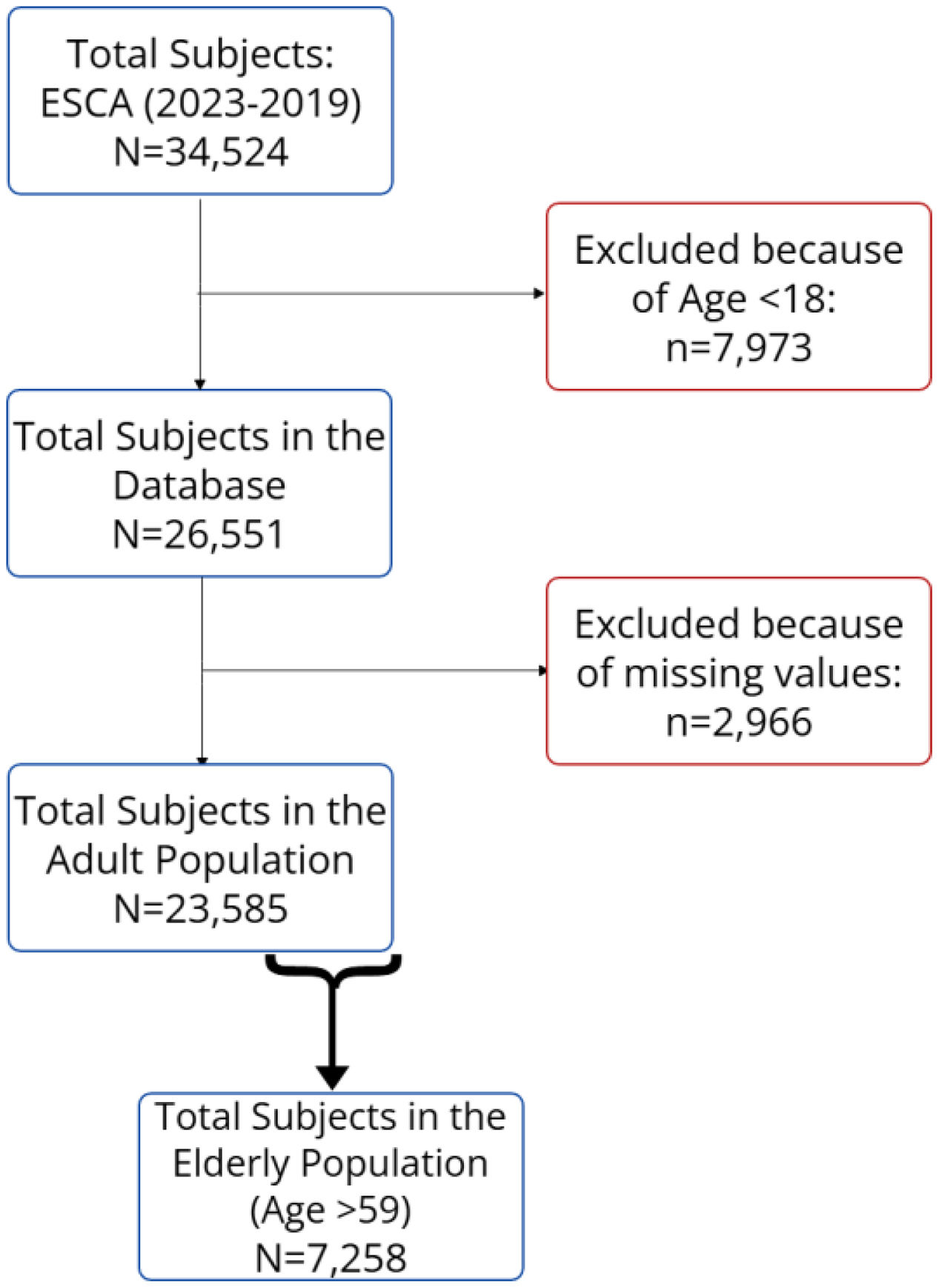

MethodDataThe dataset was drawn from the Health Survey of Catalonia (ESCA), comprising repeated cross-sectional pooled data from the 2013 to the 2019 waves. The dataset is publicly available upon request to the Ministry of Health at Generalitat de Catalunya. As depicted in Figure 1, from the 34,524 individuals included, the analysis is restricted to the adult population, resulting in a representative sample of 26,551 individuals aged 18 and older. Additionally, 11.1% of individuals are excluded due to missing values in key variables: 6% of the individuals have missing values in the loneliness variable and 5% of individuals in sociodemographic (in the poor household habitability variable (3%) and overweight variable (1.8%). This leads to a final sample of 23,585 adults and a subsample consisting of 7,258 elderly individuals (aged 60 and older). A separate and complementary analysis for the elderly subsample is made given the relatively large prevalence of loneliness among this population group.

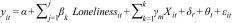

ModelThe main model, estimated using ordinary least squares methods, minimizes prediction errors and helps identify associations while controlling for key factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status. The analysis is represented by the following equation:

where yit={ait,bit} are different groups of outcomes measures. The first group (ait) includes general health as well as physical and mental health indicators. General health status is measured with one subjective indicator, self-perceived health status —which reflects whether respondents rate their health as good or not—, and another objective measure based on multi-morbidities —following Maynou et al.,29 a variable is created equal to one for individuals with two or more long-term conditions—.

Individuals at high risk of CVD are identified as those suffering from two or more cardiovascular conditions and/or diabetes. Existing literature,1 has established a strong relationship between SIL and an increased risk of CVD. Mental health variables account for depression and/or anxiety, a binary variable indicating if the individual suffers from either condition, given the strong impact of loneliness on mental health.12 The second group (bit) allows to test the effects on healthcare resource utilization, which is expected to be higher among individuals experiencing loneliness.14,15 Use of healthcare resources variable-group accounts for drug consumption or medication, visits to primary care and emergency care. Further details on variable construction are provided in Table A1 in the online Appendix.

Loneliness variable is based on the Duke-UNC Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS) and the Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3), depending on ESCA waves. DUFSS test was used in ESCA waves from 2011 to 2016, and OSSS-3 test was used from 2017 onwards. The equivalence between these two scales has been tested by the ESCA office. In order to minimise potential endogeneity, a comprehensive list of control variables has been incorporated. X is a vector including the following individual socioeconomic characteristics: age, gender (women), nationality (foreign), living alone and economic status (poor household habitability), labour market characteristics (maximum level of education completed and employment status), autonomy (lack of autonomy in ADL and/or disability status) and lifestyle (risk alcohol drinker, overweight and obesity, a smoking behaviour, diet —intake of fruits and vegetables (+5)—, and physical activity is proxy with daily walking). Territory and year fixed-effects are also included (δr and θt, respectively). εit is the classical error term.

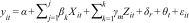

In to investigate factors contributing to the feeling of loneliness the following equation is specified:

This model enables the exploration of the role of channels.30yit denotes the binary loneliness variable. Xit is the set of covariates of interest or channels: age and gender,7,31 nationality,23–25 living alone,18,27 poor household habitability26–28 and lack of autonomy in ADL.10,19Zit is a vector of control covariates (labour market characteristics, autonomy and lifestyle) excluding those that are now covariates of interest. Health region and year fixed effects are again accounted for by δr and θt respectively. To ensure robustness, two additional analyses were conducted. First, the period is expanded to consider both tails: 2011 and 2012 —which were excluded from the main analysis as 50% of the sample has missing value in the loneliness variable—, and 2020-2022 —excluded given the reduced sample size of this wave due to COVID-19—. Including the lower-bound period (2011 and 2012) increases the sample size to 44,182 and the upper-bound period (2020, 2021 and 2022) to 56,256. Second, different elderly subsamples have been defined by setting different age cut-offs. Results keep consistent for all periods and subsamples, despite the loss of significance in some outcomes due to smaller sample size. More information is available at Table A2 in the online Appendix.

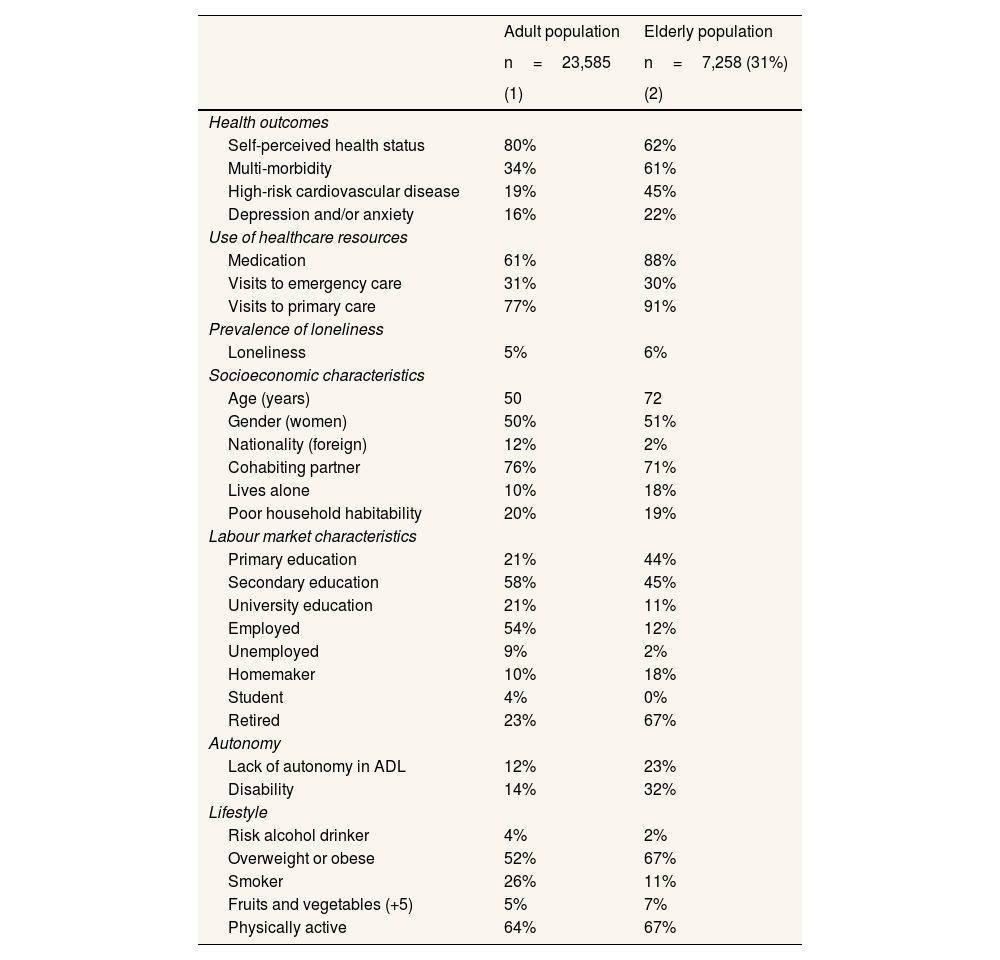

ResultsTable 1 presents descriptive statistics. The adult population (compared to elderly population) has better self-perceived health status (80% vs. 62%), fewer multi-morbidities (34% vs. 61%), and lower prevalence of high-risk of CVD (19% vs. 45%). The prevalence of depression and/or anxiety is also lower (16% vs. 22%). Healthcare resources utilization is higher for the elderly population than in the adult population, with greater medication (61% vs. 88%) and more visits to primary care (77% vs. 91%). The exception is emergency care visits, which are higher for the adult population (30% vs. 31%).

Descriptive table.

| Adult population | Elderly population | |

|---|---|---|

| n=23,585 | n=7,258 (31%) | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Health outcomes | ||

| Self-perceived health status | 80% | 62% |

| Multi-morbidity | 34% | 61% |

| High-risk cardiovascular disease | 19% | 45% |

| Depression and/or anxiety | 16% | 22% |

| Use of healthcare resources | ||

| Medication | 61% | 88% |

| Visits to emergency care | 31% | 30% |

| Visits to primary care | 77% | 91% |

| Prevalence of loneliness | ||

| Loneliness | 5% | 6% |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 50 | 72 |

| Gender (women) | 50% | 51% |

| Nationality (foreign) | 12% | 2% |

| Cohabiting partner | 76% | 71% |

| Lives alone | 10% | 18% |

| Poor household habitability | 20% | 19% |

| Labour market characteristics | ||

| Primary education | 21% | 44% |

| Secondary education | 58% | 45% |

| University education | 21% | 11% |

| Employed | 54% | 12% |

| Unemployed | 9% | 2% |

| Homemaker | 10% | 18% |

| Student | 4% | 0% |

| Retired | 23% | 67% |

| Autonomy | ||

| Lack of autonomy in ADL | 12% | 23% |

| Disability | 14% | 32% |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Risk alcohol drinker | 4% | 2% |

| Overweight or obese | 52% | 67% |

| Smoker | 26% | 11% |

| Fruits and vegetables (+5) | 5% | 7% |

| Physically active | 64% | 67% |

ADL: activities of daily living (including personal hygiene, dressing, toileting, transferring and eating).

All variables, except age, are binary variables showing the prevalence of the indicated characteristic. Self-perceived health status indicates if an individual defines their own health as good (1) or not (0).

Objective health outcomes covariates take value equal to 1 if the individual has the indicated condition. Use of healthcare resources covariates take value equal to 1 if the individual has consumed medication in the previous 15 days. Visits to emergency and primary care covariates equal to 1 if the person has used these services in the last year.

Loneliness is measured as a binary variable, indicating whether an individual experiences loneliness based on results from the DUFSS and the OSSS-3.

Loneliness is more prevalent among individuals aged 60 or older (5% vs. 6%). The proportion of women (50% vs. 51%) is higher due to women's higher life expectancy. Only 2% of individuals in the elderly population are of foreign nationality, compared to 12% in the adult population. 76% of individuals have a cohabiting partner and 10% live alone, while these figures are 71% and 18%, respectively, for the elderly population.

Poor household habitability is similarly distributed between the two samples (20% vs. 19%). Educational attainment differs: the adult population has a higher proportion of individuals with secondary (58% vs. 45%) and university education (21% vs. 11%), while primary education is more common in the elderly population (21% vs. 44%). Regarding employment status, all categories except retired and homemakers are more prevalent in the adult population. The elderly population exhibit an 11 percentage-point (pp) higher prevalence of lack of autonomy in ADL and an 18 pp higher prevalence of disabilities.

Regarding lifestyle factors, most indicators suggest a healthier lifestyle in the elderly population, except for overweight and obesity (52% vs. 67%). Specifically, alcohol risk consumption is lower (4% vs. 2%), as is the prevalence of smoking (26% vs. 11%). A higher proportion of individuals in the elderly population consume five or more servings of fruits or vegetables daily (5% vs. 7%) and are physically active (64% vs. 67%).

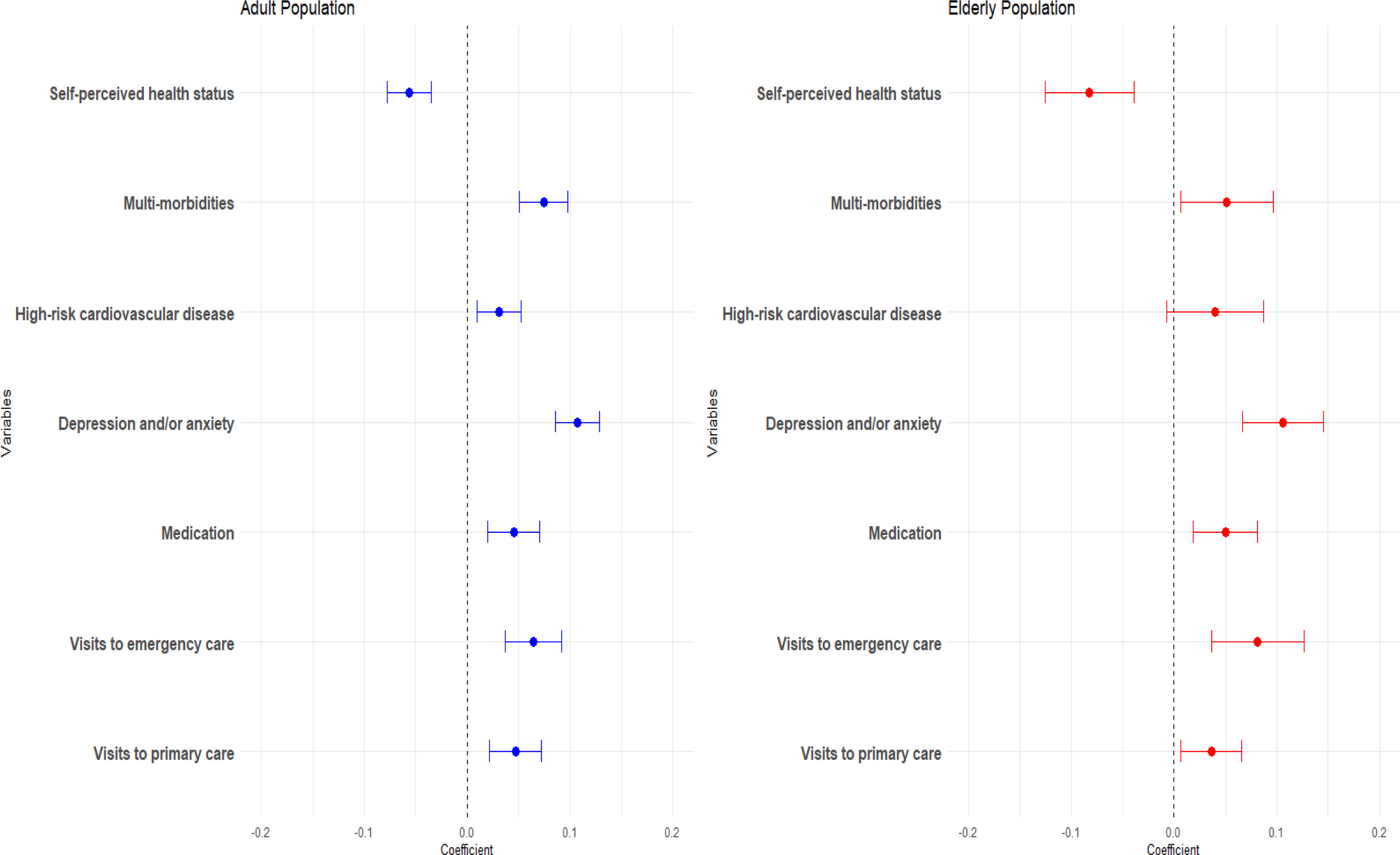

Figure 2 presents the results of estimating equation (a) graphically for adult and elderly populations. In the adult population (Fig. 2, left panel), all estimates are statistically significant. Self-perceived health status is 5.65 pp lower when experiencing loneliness (−7.1% of change in prevalence). Multi-morbidity is increased by 7.45 pp among individuals who feel lonely (+22.1%), and having high-risk of CVD in 3.1 pp (+16%). The prevalence of depression and/or anxiety is 10.74 pp higher, representing a 65.8% increase. Consequently, loneliness is associated to a 4.52 pp of taking medication (7.4%), 6.44 pp of the probability of emergency care visits (+20.9%) and 4.7 pp the probability of primary care visits (+6.1%).

Forest plot of the effects of loneliness on health and use of healthcare resources. This figure displays the estimated coefficients from regression analyses examining the association between loneliness and various health outcomes and healthcare utilization measures, separately for the adult population (left, blue) and the elderly population (right, red). Loneliness is measured as a binary variable, indicating whether an individual experiences loneliness based on results from the DUFSS and the OSSS-3. The dots represent point estimates, while the horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. A dashed vertical line at zero is included for reference, with confidence intervals overlapping zero indicating a lack of statistical significance. More information on control variables can be found in online Appendix. Source: own elaboration from ESCA data.

Figure 2 (right panel) presents the results for the elderly sample. While results are similar to the adult population, we found some significant differences. The decline in self-perceived health status associated with loneliness is more pronounced, with a coefficient of −0.0823 pp (−13.2%). In contrast, there is a smaller increase in multi-morbidities at 5.15 pp (+8.5%). However, there is no significant relationship between loneliness and high risk of CVD. For depression and/or anxiety, a coefficient of 10.61 pp indicates a 49.1% increase in prevalence. Regarding healthcare utilization, loneliness is associated with a 5.01 pp increase in medication use (+5.7%), a larger 8.13 pp increase in emergency care visits (+26.8%), and a smaller increase in primary care visits (+4.0%). The estimated coefficients of the regressions for both populations are presented in Tables A3 and A4 in online Appendix.

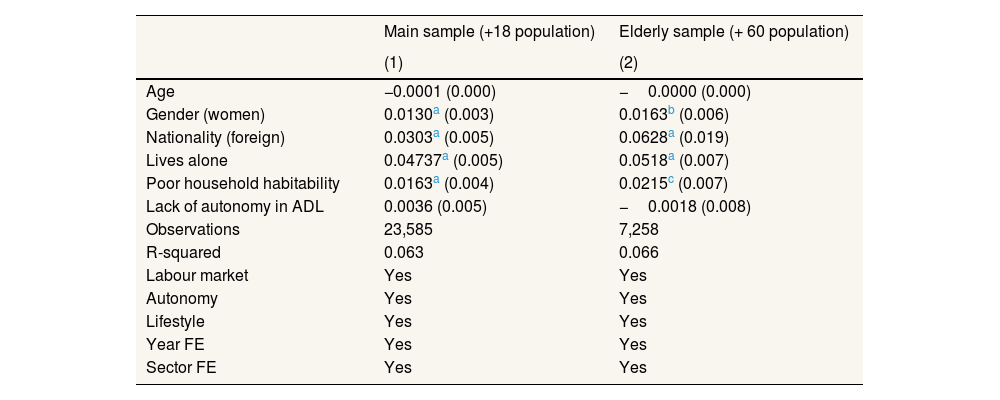

In Table 2, the estimated coefficients of equation (b) are presented for both samples in order to explore the channels or mediators explaining or predicting loneliness. Gender has a similar impact in both samples: in the adult population women exhibit a 26.8% higher prevalence of loneliness, while in the elderly population the increase is of 27.5%. Being foreign arises as a risk factor, with a coefficient of 0.03, representing a 62.4% increase in the adult population. Despite the size of the effect in elderly, the proportion of migrants in this subsample is minimal (2%), limiting the overall effects. Living alone is identified as a risk factor in both samples, with coefficients of 0.047 in the main sample and 0.05 in the elderly population. These values correspond to a 97.3% and 87.4% increase in the prevalence of loneliness respectively. Poor household habitability is also relevant for both samples, with an associated increase in the prevalence of loneliness of 33.5% and 36.3%, respectively. Finally, the lack of autonomy in ADL and age become non-significant in both samples.

Channels for loneliness, for both samples.

| Main sample (+18 population) | Elderly sample (+ 60 population) | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Age | −0.0001 (0.000) | −0.0000 (0.000) |

| Gender (women) | 0.0130a (0.003) | 0.0163b (0.006) |

| Nationality (foreign) | 0.0303a (0.005) | 0.0628a (0.019) |

| Lives alone | 0.04737a (0.005) | 0.0518a (0.007) |

| Poor household habitability | 0.0163a (0.004) | 0.0215c (0.007) |

| Lack of autonomy in ADL | 0.0036 (0.005) | −0.0018 (0.008) |

| Observations | 23,585 | 7,258 |

| R-squared | 0.063 | 0.066 |

| Labour market | Yes | Yes |

| Autonomy | Yes | Yes |

| Lifestyle | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Sector FE | Yes | Yes |

Loneliness is measured as a binary variable, indicating whether an individual experiences loneliness based on results from the DUFSS and the OSSS-3. Socioeconomic control covariates include nationality (foreign) and if suffers from poor household habitability. Labour market characteristics include the maximum level of education completed and employment status. Autonomy captures if the individual suffers a disability. Lifestyle covariates indicate if the individual is a risk alcohol drinker, is overweight or obese, a smoker, has a healthy consumption of fruits and vegetables (+5) and is physically active.

Standard errors in parentheses. FE: Fixed-Effects.

This study documents the negative effects on health associated with loneliness, while highlighting differences in its scale and nature across age groups. In the adult population, loneliness is associated with significantly worse self-perceived health, a higher probability of multi-morbidities, high risk of CVD and depression and/or anxiety. These findings align with existing evidence demonstrating that loneliness negatively impacts both physical and mental health.1 The observed 22.1% rise in the probability of multi-morbidities among lonely adults suggests that loneliness acts as a compounding factor, heightening vulnerability to the onset or progression of chronic conditions.

Among the elderly, loneliness has a stronger impact on self-perceived health, with a higher 13.2% decline, a smaller impact on multi-morbidities (+8.2%), and does not significantly affect cardiovascular disease risk. This may be due to older individuals already experiencing multiple health issues, making the additional burden of loneliness less distinguishable. The use of medication and visits to emergency care have larger estimates for the elderly. This finding is consistent with prior studies showing that socially isolated older adults often turn to emergency services due to a lack of informal care networks.14,15

As identified in the literature, living alone18,27 and migrant status,2,3,8 are the strongest predictors in both samples, reinforcing previous evidence on the importance of social living arrangements. For adults, living alone may reflect broader social disconnection or transitional life phases, whereas for older individuals, it often coincides with widowhood or diminished family networks. Poor household habitability plays a significant role, supporting research linking poverty to social isolation.9,10 Our findings align with literature, suggesting women report more loneliness across all age groups.11 Notably, the lack of a strong association between age and loneliness suggests that age per se is not a crucial driver, but other factors are the ones that matter.

The role of employment status as a channel for loneliness has been investigated and is only relevant for the adult population, as a large fraction of the elderly population is retired. Significant effects were found for being employed or a student as a protector from loneliness, while being unemployed, retired or a homemaker were identified as drivers towards loneliness. Overweight, another factor highlighted in the literature as a contributor to loneliness, is significant only in the adult population.32

ConclusionsIn a context of growing loneliness, this analysis documents the negative impact of loneliness on health and healthcare use, using data from the ESCA. These effects are robustly identified. A significant negative association of loneliness with subjective and objective general health indicators is found, as well as in three of the most relevant indicators of physical and mental health: multi-morbidities, high risk of CVD and depression and/or anxiety. These results align with broader literature, which documents the deleterious effects of loneliness on both physical and menta l well-being.8–10,14,15 For elderly population, loneliness further pushes for declines in self-perceived health and increases emergency care visits, suggesting a gap in accessible preventive and social care services for older adults.

Living alone, migrant status, being a women or poverty are key determinants of loneliness, suggesting the need for targeted interventions to mitigate loneliness through a multi-faceted approach. Public health strategies should incorporate community-based programs aimed at fostering social connections, enhancing accessibility to support networks, and integrating loneliness screening into routine healthcare services. Indeed, it has been claimed that healthcare professionals in primary care are key to identifying and preventing loneliness.33 Alternatively, social service units, in charge of long-term care programmes can also lead this multifaceted intervention, as in Nexes program.34 Older adults’ frequent healthcare use allows professionals to address social isolation and its impacts. Furthermore, policies promoting intergenerational living and social housing could serve as preventative measures.

Although the analysis incorporates a rich set of control variables, the threat of reverse causality or unobserved confounders cannot be neglected. Cross-sectional design further limits the ability to infer causal relationships, necessitating the interpretation of findings as associations. Additionally, institutionalized individuals, excluded from the ESCA sample, may also experience loneliness despite cohabiting. Similarly, we have excluded 6% of the original ESCA sample due to missing information on the loneliness indicator.

The lack of significant effect of the loss of autonomy on loneliness contrasts with previous evidence. Future research should explore a possible heterogeneous effect of this factor given that some impairments, such as hearing, are more prone to affect SIL.35 Similarly, the strong effects of living alone and migrant status suggest that social care interventions could help mitigate loneliness. Therefore, further research could explore to which extent. Last but not least, a step further should investigate the overall cost of loneliness for healthcare: on the one hand, loneliness is associated with premature death; on the other hand, it is linked to worse health and higher healthcare services utilization. In short, this analysis highlights the need for integrated care strategies and research to better understand and address loneliness.

Availability of databases and material for replicationThe dataset is publicly available upon request from the Ministry of Health of the Generalitat de Catalunya.

The literature suggests that loneliness and social isolation significantly deteriorate health outcomes across various populations, particularly in older adults, with adverse effects on mental health and healthcare utilization.

What does this study add to the literature?This study provides evidence on how loneliness differentially impacts health and healthcare use across age groups in Catalonia, highlighting specific risk pathways.

What are the implications of the results?The results underscore the need for targeted public health interventions to tackle loneliness and enhance social connections to prevent health deterioration and maintain desirable levels of quality of life.

Vicente Ortún.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsH.M. Hernández-Pizarro and A. Prades-Colomé: Study conception and design, data gathering, data analysis, article writing, and critical review with significant intellectual contributions. G. López-Casasnovas: Critical review, approval of the final version for publication, and ensuring all manuscript parts were reviewed for accuracy. All authors contributed to the discussion and approval of the final manuscript.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank the participants at the Spanish Health Economics Association annual meeting (Jornadas AES) and Centre for Research in Health and Economics (CRES-UPF) for the useful comments and suggestions. We would like to thank Antonia Medina, Anna Schiaffino and the SGAIPE Unit of Catalan Health Department for providing data and insight of the dataset. Hernández-Pizarro and López Casasnovas acknowledge financial support from AGAUR SGR-2021 SGR 00966. Errors remain our own.

FundingHernández-Pizarro and López Casasnovas acknowledge financial support from AGAUR SGR-2021 SGR 00966.

Conflicts of interestsNone.