To explore the use of smartphones at mealtimes by children in fast food restaurants in the city of Barcelona and to assess the variables associated with this use.

MethodA cross-sectional study was carried out. Data from 1616 children of estimated ages between 4 to 10 years were collected in fast-food restaurants in the ten districts of Barcelona between October 2021 and July 2022. The percentage of smartphone use, overall and according to covariates, were calculated. Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests, and crude and adjusted Poisson regression models with robust variance, were carried out to assess the association between use and covariates.

ResultsDirect observation revealed that in 28.1% of meals with children at fast food restaurants, children used smartphones. Smartphone use was significantly higher in older children if their caregivers were younger than 30 years and when there was no caregiver-child interaction. In the adjusted model, higher patterns of smartphone use were associated with older children (aPR [95% CI]: 1.36[1.20-1.55]) and younger parents (aPR [95% CI]: 1.38[1.09-1.73]).

ConclusionsAlmost one in three meals with children at fast-food restaurants in Barcelona involves smartphone use. This finding underlines the importance of raising awareness of responsible screen use and promoting healthier environments for children at mealtimes.

Explorar el uso de smartphones en los actos de comida en niños/as en restaurantes de comida rápida de la ciudad de Barcelona y evaluar las variables asociadas a este uso.

MétodoSe llevó a cabo un estudio transversal. Se recogieron datos de 1616 niños/as de edades estimadas entre 4 y 10 años en restaurantes de comida rápida de los diez distritos de Barcelona entre octubre de 2021 y julio de 2022. Se calculó el porcentaje de uso de smartphones, global y según covariables. Se realizaron pruebas de Chi-cuadrado y exacta de Fisher, y modelos de regresión de Poisson crudos y ajustados con varianza robusta, para evaluar la asociación entre el uso y las covariables.

ResultadosLa observación directa reveló que en el 28,1% de las comidas realizadas con niños/as en restaurantes de comida rápida, estos/estas utilizaban smartphones. El uso de smartphones fue significativamente mayor en niños/as mayores, si sus cuidadores/as eran menores de 30 años y cuando no había interacción entre cuidador/a y niño/a. En el modelo ajustado, los patrones más altos de uso de teléfonos inteligentes se asociaron con niños mayores (aPR [95% IC]: 1.36[1.20-1.55]) y padres más jóvenes (aPR [95% IC]: 1.38[1.09-1.73]).

ConclusionesEn casi una de cada tres comidas con niños/as en restaurantes de comida rápida de Barcelona se utiliza el smartphone. Este hallazgo subraya la importancia de concienciar sobre el uso responsable de las pantallas y promover entornos más saludables para los/las niños/as en el momento de comer.

The Sedentary Behavior Research Network defined screen time as time spent on behaviors (sedentary or active) involving the use of screens.1 Currently, it is very common to spend a lot of time in front of screens as we live surrounded by technology.2 Importantly, it is mainly children who are increasing their use of technology.3 In Spain, it was estimated in 2017 that 29.3% of children under 14 used screens less than 1 hour a day for recreational purposes, 26.4% between 1 and 2hours, 28.6% between 2 and 3hours, and 15.7% more than 3hours.4

The widespread use of different screen devices in children is modifying their behavioral patterns, such as sedentary behavior, daily eating habits, and sleep patterns, as well as general health and psychological well-being.5 Despite the large number of deleterious outcomes asociated with excessive use of screen devices,6,7 the most controversial aspect and the one that generates public alarm is their potential for addiction.8–10 Beyond problematic use, some authors have suggested some benefits associated with the use of screen devices.11 Such benefits include the positive attitude towards oneself derived from relationships with friends,12 the ease of communication, and even the use of the smartphone as a device to overcome boredom.13 Likewise, the maintenance of family bonds14 and better educational outcomes11 can be highlighted as positive aspects of the use of screen devices.

Nowadays, smartphones may serve as a distraction tool in family situations where the child is stressed or must wait, such as eating away from home.15 However, excessive smartphone use could isolate children from social interactions with their families, missing the opportunity to converse and enjoy the company of those around them. Importantly, in the context of child development,16 family communication and interactions during mealtimes have a significant influence on both the physiological and psychological well-being of the child.17 As such, it is important to explore the physical and social contexts of screen engagement during mealtimes to better develop interventions that seek to encourage the optimal use of smartphones. However, there are not many studies exploring the use of screen devices during meals, in particular in Europe, where just a study in Italy found that 59.5% of families used a smartphone during mealtimes in fast-food restaurants.18 In Lithuania, 33.7% of children (aged 2 to 5 years old) were exposed to smartphones during meals periodically, a few times each week or month; and 22% daily or during every meal.19 Relevantly, it is becoming common to see children using smartphones while eating, in fast food restaurants20,21 which are part of obesogenic environments,22 and where families are more likely to allow the use of smartphones to entertain children.23

Regarding the predictors of the use of screen devices, many studies have shown that screen use is associated with socioeconomic level,24 caregiver education,25 and caregiver use of the device.26 Nevertheless, most of the evidence is derived from traditional forms of screen use (e.g., TV viewing, and computer use), and less is known about the predictor variables of newer forms of screen devices, such as smartphones. Overall, in Spain, there are no data on the prevalence and predictors of smartphone use by children in fast-food restaurants. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the use of smartphones at mealtimes by children in fast-food restaurants in the city of Barcelona (Spain).

MethodDesignCross-sectional study using discrete, structured, direct observation.

Population and sampleA convenience sample of children aged approximately 4 to 10 years (n=1616) was directly observed in fast-food restaurants in the city of Barcelona (Spain).

The sample size was estimated on the basis that a sample of 1592 children of estimated ages between 4 to 10 years is sufficient to estimate, with 95% confidence and a precision of ±2 percentage units, a population percentage of smartphone use expected to be around 21%.22

Data collectionBefore starting the main study, a pilot study was conducted to estimate the concordance in the observations made by two researchers who conducted the fieldwork (SdPC, IC). As the pilot study showed a high concordance (Cohen's kappa index=0.90), these data were incorporated into the main study.

To conduct data collection, random observation routes were designed. For this purpose, the best-known fast-food restaurants in Spain (i.e., McDonald's, Burger King, Domino's Pizza, Five Guys, and Kentucky Fried Chicken) in each district of Barcelona were selected. Within each district, two different geographical points were randomly chosen to start and end the observation. Random routes were carried out in districts with a higher number of fast-food restaurants. However, in the district of Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, no random routes were carried out because there were only three fast-food restaurants (i.e., Burger King, Domino's Pizza, and Kentucky Fried Chicken). The sampling times were lunchtime (from 12:00 to 14:00) and dinnertime (from 20:00 to 24:00). Sampling was carried out 3 days a week from October 2021 to July 2022, although our efforts were concentrated on weekends since these are the days when children visit fast-food restaurants more frequently.

The observation was covert by one researcher at a time and consisted of observing eating events with children in fast-food restaurants. The observation time was approximately 15minutes per group if smartphones were not used, as this is the average time children take to eat, as reported elsewhere.27 If the child started using the smartphone during the observation, this was extended 15minutes from that moment. If no child entered the restaurant within 10minutes, we continued the route to the next restaurant to save time and effort, as the routes averaged 2hours.

InstrumentAn observation template was designed to collect data on 19 variables related to smartphone use and child, caregiver, food, and environmental factors.

Variables1)OutcomesThe main outcome was smartphone use (yes/no). Use was defined as any instance of the child using the smartphone during the observation period (before the meal, during the meal, and/or after the meal).

2)CovariatesChild-related variables included sex (male, female), estimated age (4-6 years, 7-10 years), estimated weight (underweight/normal weight or overweight/obesity), and child's attitude (bad, good, neutral). Bad attitude was defined as when the child shouted, or remained angry. Good attitude was defined as having a positive attitude and following instructions, and neutral as having no emotion, either positive or negative. Variables related to caregivers were sex (male, female, both: referring to the presence of two people of different sex), estimated age (<30 years, 30-40 years, >40 years), and estimated level of caregiver-child interaction (no interaction, little interaction, high interaction). Interaction was defined as if there was reciprocal action between the child and the caregiver. For instance, if the interaction was simply showing a picture or saying a word, it was considered as little interaction. On the contrary, if they engaged in a conversation, it was considered a high interaction. Other variables that were observed were related to the type of meal (hamburger, pizza, other), the mealtime (lunch, dinner), and whether the children finished the meal (yes, no).

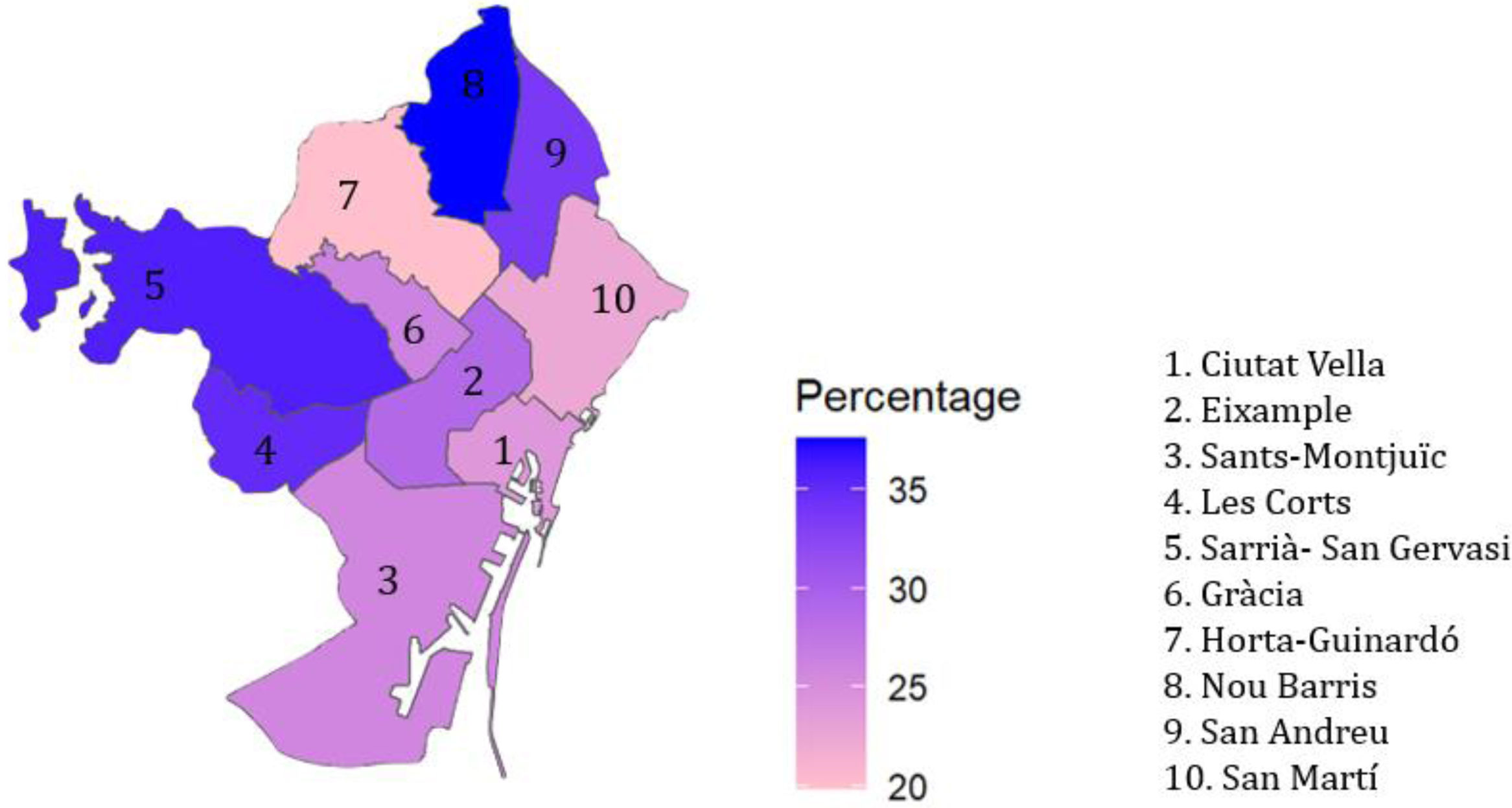

Furthermore, we collected data related to the environment: place of observation (indoors, outdoors), if the restaurant had playground area (yes, no), use of toys during the observation period (yes, no), weather (rainy day, sunny day), day of the week (from Monday to Sunday) and the district of Barcelona (Ciutat Vella, Eixample, Sants-Montjuïc, Les Corts, Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, Gràcia, Horta-Guinardó, Nou Barris, Sant Andreu, Sant Martí). The socio-economic classification of the districts (high, medium, or low) was defined according to the average income level per person in each district 28. The lower-class districts were: Sants-Montjuïc, Horta-Guinardó, Nou Barris, and Sant Andreu; the medium-class districts were: Eixample, Gràcia, and Sant Martí; and the higher-class districts were Sarrià- Sant Gervasi, Ciutat Vella, and Les Corts.

3)Data analysisAll statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.2) and RStudio (version 2021.09.0/B351).

The percentage of smartphone use in fast-food restaurants, overall and stratified by covariates, were calculated and Chi-squared tests and Fisher's exact tests were carried out. Crude (PR) and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated by fitting Poisson regression models with robust variance. Multivariable regression models were adjusted for the sex of the child, the estimated age of the child and the estimated age of the caregivers.

4)Ethical aspectsThe present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya, Barcelona (2021/09-PED-HUGC) and was carried out according to the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects included in the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 (Word Medical Association, 2013).

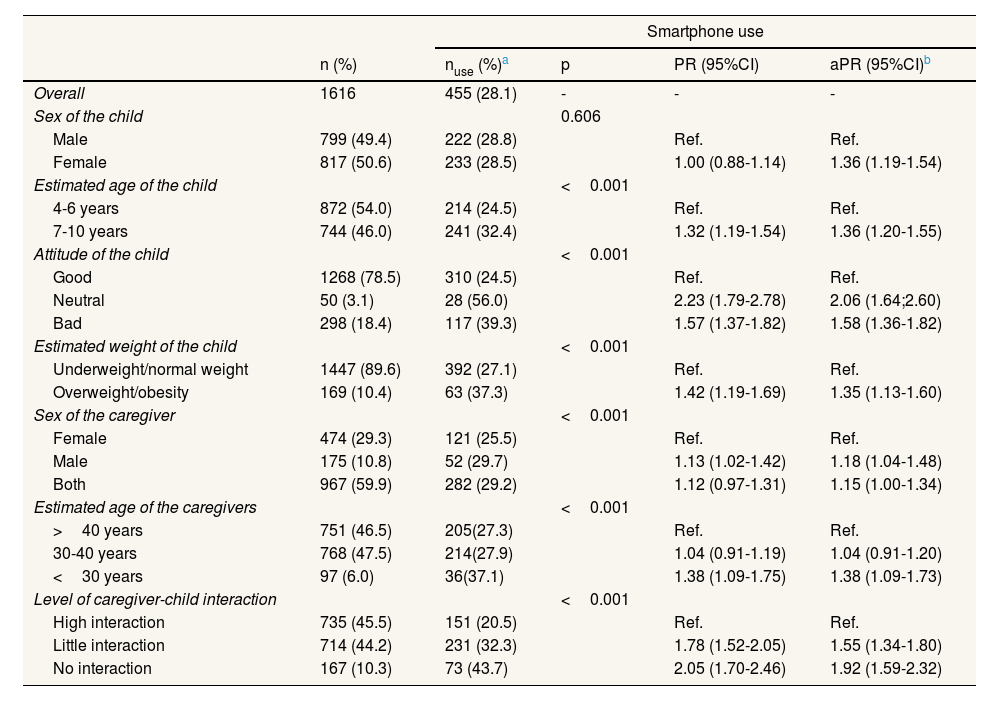

ResultsOf the total sample of children (n=1616), 50.6% were classified as female, 54.0% were of an estimated age of 4-6 years, 89.6% were estimated to have underweight or normal weight, and 47.5% of the caregivers were of estimated ages 30-40 years (Table 1).

Percentage of smartphone use in fast-food restaurants, overall and according to covariates, and crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) for the association between use and covariates (Barcelona, 2021-2022).

| Smartphone use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | nuse (%)a | p | PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI)b | |

| Overall | 1616 | 455 (28.1) | - | - | - |

| Sex of the child | 0.606 | ||||

| Male | 799 (49.4) | 222 (28.8) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Female | 817 (50.6) | 233 (28.5) | 1.00 (0.88-1.14) | 1.36 (1.19-1.54) | |

| Estimated age of the child | <0.001 | ||||

| 4-6 years | 872 (54.0) | 214 (24.5) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 7-10 years | 744 (46.0) | 241 (32.4) | 1.32 (1.19-1.54) | 1.36 (1.20-1.55) | |

| Attitude of the child | <0.001 | ||||

| Good | 1268 (78.5) | 310 (24.5) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Neutral | 50 (3.1) | 28 (56.0) | 2.23 (1.79-2.78) | 2.06 (1.64;2.60) | |

| Bad | 298 (18.4) | 117 (39.3) | 1.57 (1.37-1.82) | 1.58 (1.36-1.82) | |

| Estimated weight of the child | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight/normal weight | 1447 (89.6) | 392 (27.1) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Overweight/obesity | 169 (10.4) | 63 (37.3) | 1.42 (1.19-1.69) | 1.35 (1.13-1.60) | |

| Sex of the caregiver | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 474 (29.3) | 121 (25.5) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Male | 175 (10.8) | 52 (29.7) | 1.13 (1.02-1.42) | 1.18 (1.04-1.48) | |

| Both | 967 (59.9) | 282 (29.2) | 1.12 (0.97-1.31) | 1.15 (1.00-1.34) | |

| Estimated age of the caregivers | <0.001 | ||||

| >40 years | 751 (46.5) | 205(27.3) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 30-40 years | 768 (47.5) | 214(27.9) | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) | 1.04 (0.91-1.20) | |

| <30 years | 97 (6.0) | 36(37.1) | 1.38 (1.09-1.75) | 1.38 (1.09-1.73) | |

| Level of caregiver-child interaction | <0.001 | ||||

| High interaction | 735 (45.5) | 151 (20.5) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Little interaction | 714 (44.2) | 231 (32.3) | 1.78 (1.52-2.05) | 1.55 (1.34-1.80) | |

| No interaction | 167 (10.3) | 73 (43.7) | 2.05 (1.70-2.46) | 1.92 (1.59-2.32) | |

aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio; Ref: reference category.

Overall, 28.1% of meals at fast-food restaurants with children involved smartphone use. Among the children who used smartphones in fast-food restaurants, 23.2% of the children used them while waiting for the meal, 34.9% used them during the meal itself, 17.36% during the after-meal, and 0.2% during the three observation times. There were no significant differences in smartphone use between males and females. Children with an estimated age between 7 to 10 years showed significantly higher smartphone use at any time of observation compared to children aged 4 to 6 years (32.4% vs. 24.5%; p=<0.001). Children with bad and neutral attitude had a significantly higher adjusted probability of used (aPR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.36 1.82 and aPR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.64 2.60) as compared with those with good attitude. Furthermore, the adjusted probability of using smartphones in children at any time of observation who were classified as overweight or obese was 35% higher than in children with estimated underweight or normal weight (aPR: 1.35; 95%CI: 1.13-1.60). According to districts, the highest smartphone use at any time of observation was observed in Nou Barris, while the lowest was observed in Horta-Guinardó (37.0% vs. 19.8%, respectively) (Fig. 1). The district with the highest adjusted smartphone usage was Sarrià-Sant Gervasi (aPR: 1.91; 95%CI: 1.19-3.08), compared to Horta-Guinardó (Table 2).

Percentage of smartphone use in fast-food restaurants, overall and according to covariates, and crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) for the association between use and covariates (Barcelona, 2021-2022).

| Smartphone use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | nuse (%)a | p | PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI)b | |

| Type of food | <0.001 | ||||

| Pizza | 27 (1.7) | 4 (14.8) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Burger | 1394 (86.3) | 391 (28.0) | 1.54 (0.79-3.00) | 1.61 (0.84-3.09) | |

| Other | 195 (12.1) | 60 (30.8) | 1.69 (0.85-3.36) | 1.69 (0.86-3.31) | |

| Meal time | <0.001 | ||||

| Lunch | 875 (54.1) | 213 (24.3) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Dinner | 741 (45.9) | 242 (32.7) | 1.30 (1.14-1.48) | 1.30 (1.14-1.47) | |

| Finished meal | 0.044 | ||||

| No | 790 (48.9) | 206 (26.1) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Yes | 826 (51.1) | 249 (30.1) | 1.17 (1.02-1.33) | 1.08 (0.95-1.24) | |

| Barcelona district | <0.001 | ||||

| Ciutat Vella | 216 (13.4) | 49(22.7) | 1.21 (0.83-1.77) | 1.23 (0.84-1.79) | |

| Eixample | 253 (15.7) | 72 (28.5) | 1.45 (1.01-2.08) | 1.46 (1.02-2.09) | |

| Sants-Montjuïc | 132 (8.2) | 34 (25.7) | 1.30 (0.87-1.94) | 1.35 (0.90-2.02) | |

| Les Corts | 146 (9.0) | 51 (34.9) | 1.76 (1.22-2.56) | 1.78 (1.23-2.59) | |

| Sarrià- Sant Gervasi | 39 (2.4) | 12 (30.8) | 1.81 (1.12-2.92) | 1.91 (1.19-3.08) | |

| Gràcia | 103 (6.4) | 27 (26.1) | 1.32 (0.87-2.01) | 1.37 (0.90-2.08) | |

| Horta-Guinardó | 106 (6.6) | 21 (19.8) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Nou Barris | 189 (11.6) | 70(37.0) | 1.90 (1.33-2.71) | 1.90 (1.33-2.73) | |

| Sant Andreu | 217 (13.4) | 72 (33.1) | 1.70 (1.19-2.43) | 1.75 (1.22-2.49) | |

| Sant Martí | 215 (13.3) | 47 (21.9) | 1.13 (0.77-1.65) | 1.08 (0.74-1.59) | |

| Location | <0.001 | ||||

| Indoors | 1261 (78.0) | 327 (25.9) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Outdoors | 355 (22.00) | 128 (36.1) | 1.38 (1.20-1.59) | 1.36 (1.18;1.56) | |

| Playground | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 111 (6.9) | 29 (26.1) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| No | 1505 (93.1) | 426 (28.3) | 1.37 (1.22-1.69) | 1.39 (1.23-1.70) | |

| Weather | <0.001 | ||||

| Rainy day | 372 (23.0) | 85 (22.8) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Sunny day | 1244 (77.0) | 370 (29.7) | 1.33 (1.12-1.58) | 1.29 (1.08-1.54) | |

| Toy usage | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 886 (53.6) | 176(19.9) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| No | 730 (46.4) | 279 (38.2) | 1.93 (1.69-2.21) | 1.85 (1.61-2.12) | |

| Weekday | <0.001 | ||||

| Monday | 15 (1.0) | 3 (20.0) | 1.80 (0.57-5.68) | 2.07 (0.68-6.29) | |

| Tuesday | 78 (4.8) | 28 (35.9) | 3.23 (1.43-7.29) | 3.51 (1.59-7.77) | |

| Wednesday | 36 (2.3) | 3 (8.3) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Thursday | 83 (5.1) | 22 (26.5) | 2.39 (1.03-5.50) | 2.48 (1.10-5.57) | |

| Friday | 275 (17.0) | 100 (36.4) | 3.30 (1.50-7.25) | 3.39 (1.58-7.28) | |

| Saturday | 710 (43.9) | 209 (29.4) | 2.67 (1.22-5.84) | 2.76 (1.29-5.90) | |

| Sunday | 419 (25.9) | 90 (21.5) | 2.04 (0.93-4.49) | 2.15 (1.00-4.63) | |

aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

The percentage of smartphone use during meals was significantly higher in children accompanied by a male adult or both than in children accompanied by a female. The adjusted probability of using smartphones of children accompanied by caregivers younger than 30 was 38% higher than that in children accompanied by older caregivers (aPR: 1.38; 95%CI: 1.09-1.73). In addition, when there was no interaction between the caregiver and child, the adjusted probability of using a smartphone increased by 55% (aPR: 1.55; 95%CI: 1.34-1.80).

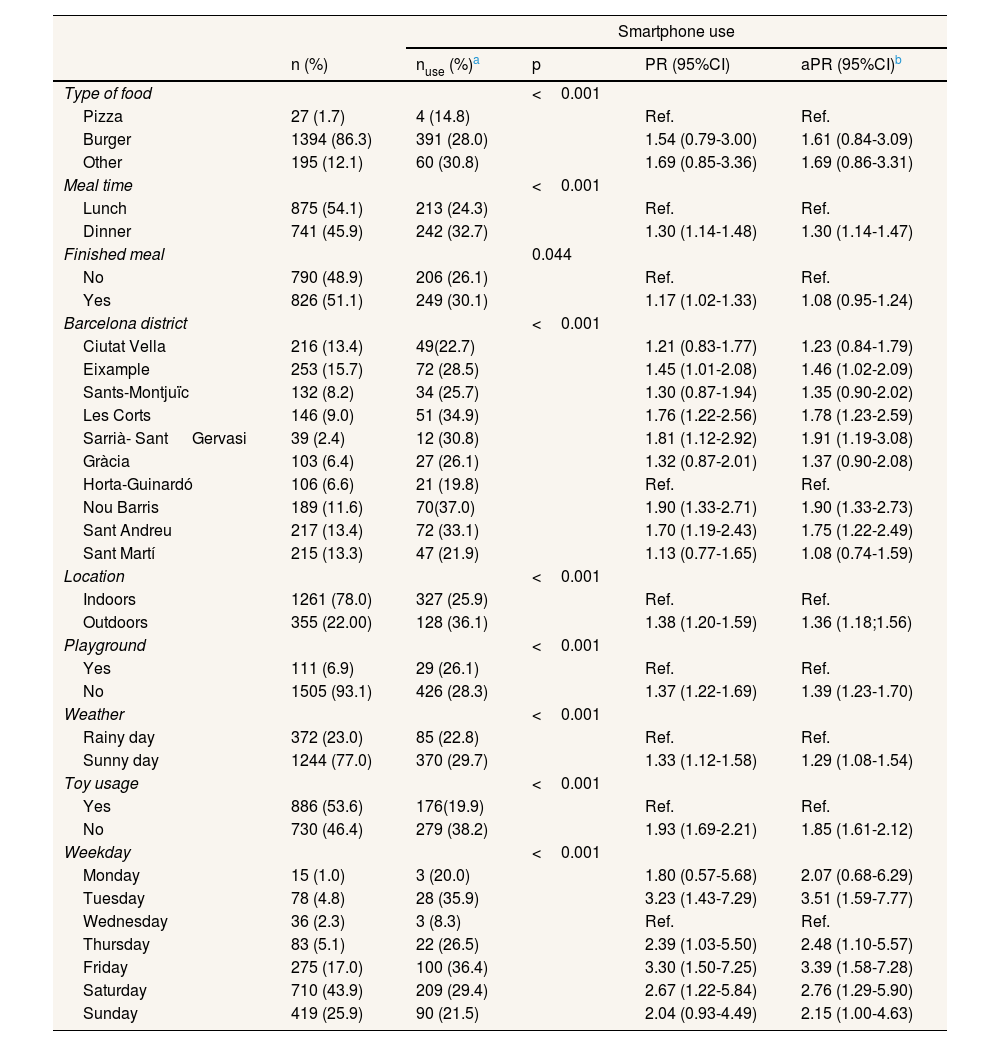

As shown in Table 2, the adjusted probability of using a smartphone in fast-food restaurants increased by 8% for children who finished the meal (aPR: 1.08; 95%CI: 0.95-1.24). In observations taken outdoors, the adjusted use of smartphones was significantly higher (aPR: 1.36; 95%CI: 1.18-1.56). In addition, in fast-food restaurants that did not have playgrounds or toys to play with, the use of smartphones was also higher (aPR: 1.39; 95%CI: 1.23-1.70). We found that on Thursdays there was a higher adjusted use of smartphones by children (aPR: 3.51; 95%CI: 1.59-7.77) compared with Wednesday (Table 2).

DiscussionOur study showed that children used smartphones in 28.1% of meals with children observed in fast-food restaurants. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to explore childrens’ use of smartphones in fast-food restaurants in Spain. Our main results are consistent with the previous studies that have directly examined children's use of smartphones during mealtimes in restaurants from other countries.18–20 Other studies have examined the use of smartphones by caregivers in similar settings.20,29,30 This finding is consistent with the global trends of increasing access to digital devices, integration of technology into daily life, and early use of technology.31 The relaxed environment of fast-food restaurants may be a key contributing factor to the increase in children's smartphone use during mealtimes. In these establishments, where the atmosphere is more informal, families tend to be more permissive with the use of digital devices as a tool to entertain their children during waiting times for meals. The increasing usage of screen devices has created distance between children and their caregivers.32 For that reason, it is therefore important that children follow screen-use recommendations of pediatric guidelines.33 Experts recommend limiting screen time for children between the ages of 0 to 5,34 due to the detrimental effects of screen time on their health and well-being.6,7,35

The causes and consequences of smartphone use differ depending on whether it occurs before, during, and after meals. In the present study, the smartphone was used at any time during the observation in almost one in three of the observed mealtimes. According to our study among children using smartphones, 23.9% of the children used their device while waiting for the meal, may be associated with boredom during waiting time. 34.9% of children use their devices during meals, which may be due to a cycle of anxiety13 that is temporarily reduced through increasing caloric intake.36 Lastly, 17.36% of children used their devices post-meal.

In our study, smartphone use during meals was higher in the older age group (7-10 years). Older children (7-10 years) tend to have more autonomy, which resulted in a higher level of perceived freedom to use their smartphones. In addition, children with a neutral attitude (when the child remained absent/silent) may seek more external stimulation or entertainment to satisfy their emotional needs, and the smartphone may provide an easy distraction. Compared to children with positive and neutral attitudes, those with a bad attitude had a significantly greater adjusted likelihood of being exposed to the smartphone (aPR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.36 1.82). This may be because caregivers use the smartphone to calm or entertain the child when the child is misbehaving. Additionally, the use of smartphones during meals was 35% higher in overweight or obese children in comparison to those who were underweight or normal weight. This may be due to the fact that higher smartphone usage is often associated with a more sedentary lifestyle, contributing to weight gain and obesity. Based on the findings of a Spanish study, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was higher in children whose screentime was above 120minutes, compared to those whose screentime was less than 59minutes a day.37

In our study, we observed that during mealtimes (at any time of observation) smartphone use had varying effects on social interaction. In some instances, smartphone use led to a decrease in social interaction, while in other cases, it appeared to increase interactions once the child began using their smartphone. Specifically, our findings indicated that in the absence of a caregiver-child interaction in fast-food restaurants, the adjusted likelihood of smartphone use rose by 55%, independent of the time of observation. Our results demonstrated that children accompanied by younger caregivers (under the age of 30) were more likely to use their smartphones at any time of observation (37.1%). This may be because younger caregivers are influenced by social trends that encourage the use of technology in parenting. Along these lines, according to our study, children were more likely to use a smartphone when their caregiver was a male. This could be due to the tendency of male caregivers to be more permissive with their children and to provide smartphones as a means of relaxation and enjoyment for both parties.38 Some caregivers also believe that screen use is beneficial for children,39 due to its provision of educational and entertaining content while allowing the caregivers to enjoy a quiet mealtime; nevertheless, other caregivers remain concerned about the negative impacts that screens may have on the child's social development.11

Finally, playgrounds or toys provided by restaurants for children can entertain children by reducing the use of smartphones. In this context, establishments supplying paper and pencils for children can also help reduce the use of technology. This initiative should be promoted in more establishments to make healthier use of screen devices by children.

LimitationsFirstly, we have estimated different variables like the age of the caregiver and their child, among other variables, which is a limitation associated with direct observation. For this purpose, we performed a pilot study and computed Cohen's kappa index, showing high concordance (0.90), which can reduce the bias of direct observation between observers. Secondly, the validity of collecting variables with the level of detail as in the case of obesity must be assessed. Thirdly, the variable of smartphone use was only recorded categorically (yes/no) and not quantitatively. Due to the direct observation design of the study, it was very difficult to estimate quantitative variables. It may be beneficial to use cameras in future investigations to obtain quantitative estimates. Furthermore, the election of fast-food establishments as a venue to perform the direct observation could affect the external validity of the study, such that the relaxed environment of fast-food restaurants may be a key contributing factor to the increase in children's smartphone use at any time of observation. However, we selected these venues because these establishments are more frequented by families with children than other more formal restaurants. Moreover, the informal setting of these establishments allowed the observers to enter and collect data whilst remaining unnoticed during the observation. Finally, the length of the observation was different between users and non-users of the smartphone. For children who did not use the smartphone during the observation, we based our observation on the 15-minute observation of the duration of the meal. However, for the children who did use the smartphone, we counted the 15minutes from the time of contact with the device to observe whether they finished the meal. Our results could have therefore underestimated the time of smartphone use as the probability of smartphone use tends to increase with observation time. Our work only recorded the presence of smartphone usage (use or non-use); however, other important aspects of smartphone use such as intensity or content viewed were not recorded. Future studies should focus on these unaddressed aspects to better understand the impact of this new determinant of health during mealtimes. To understand all subjective aspects of this determinant of health, a qualitative study is warranted in the future.

ConclusionsNearly one in three meals in fast-food restaurants involves the use of a smartphone by children. The prevalence of smartphone use during meals was higher in older children, those with bad attitudes, those who were overweight or obese, those accompanied by younger female caregivers, and when there was no interaction between the child and the caregiver. The results of this study will be valuable to caregivers, educators, and restaurant owners, as they could help raise awareness (especially among caregivers of children) of the prevalence of smartphone usage in fast-food restaurants. It is therefore important to enforce limits regarding screen use in hospitality settings to encourage quality family mealtime.

Smartphones are increasingly being used during meals. Longer periods of screen time are associated with deleterious health outcomes in children.

What does this study add to the literature?Nearly one out of three children observed in fast-food restaurants used a smartphone in our sample. There is a high percentage of children who used smartphone in districts of low socioeconomic status.

What are the implications of the results?Overexposure to electronic devices during meals could affect the cognitive development and attention span of children. The distraction caused by screens can negatively affect eating habits. Additionally, constant exposure to advertising on electronic devices during meals could influence children's food choices. Using devices during meals can decrease quality time family by reducing face-to-face interactions and communication between members of the family.

Databases are not available for public use.

Editor in chiefJosé Manuel Jiménez Rodríguez.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described. Databases are not available for public use.

Authorship contributionsS. de Paz-Cantos: design and conceptualisation, investigation, writing-original draft, methodology, acquisition, curation, analysis and interpretation of data, software, formal analysis, writing-critical review and editing. A. González-Marrón: conceptualisation, methodology, data interpretation, writing-critical review and editing. C. Lidón-Moyano: conceptualisation, methodology, and writing-critical revision. I. Cabriada: data analysis and interpretation. M. Cerrato-Lara and R. Gómez-Galán: methodology and data interpretation. JM. Martínez Sánchez: conceptualisation, methodology, data interpretation, writing-critical review and editing.

AcknowledgementsTo all the members of the Health Determinants and Health Policies team at the International University of Catalunya, whose dedication and experience have greatly enriched the research work. We also thank Isabela Reis and Angelina Kozhokar, medical students at the International University of Catalunya, for their contribution to the data collection.

FundingThis study has been funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain (ref.: PID2021-122272OBI00) and by ERDF/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) funds - a way to build Europe. The Health Determinants and Health Policy Evaluation Group is supported by the Department of Universities and Research of the Generalitat de Catalunya (grant number 2021SGR00186).

Conflicts of interestNone.