The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoThis study aimed to analyze the relationship of behavioral risk factors for periodontal disease among 19–64 age group in Malang City.

MethodA non-experimental quantitative analytic with a cross sectional study approach was used in this study. The respondents were 331 patients who visited the dental clinics of the Health Centers in Malang City. A cluster random sampling technique was used in this study. The instrument used was questionnaire. The data analysis was done through multivariate analyses use logistic-regression.

ResultsThe Wald test results on logistic-regression models showed there is no significant effect of smoking habits and consumption patterns on periodontal disease. There is a significant effect of systemic disease on periodontal disease with a significance value of 0.000 (p<0.05).

ConclusionsThere was a significant relationship and effect between systemic disease and periodontal disease in this study.

Periodontal disease is a chronic disorder marked and categorized by inflammation and damage to the supporting tissues of the teeth and infects more than half of the world's adult population.1 According to the Global Burden of Disease Study from 2016, severe periodontal disease ranks 11th in prevalent diseases in the world.2 According to data from Indonesian Basic Health Research or Riset Kesehatan Dasar (RISKESDAS), the national prevalence of dental and oral health issues in Indonesia in 2013 was 25.9%, while the prevalence in East Java was 54.4% with the highest prevalence being in Malang City (72%).3 Preliminary studies conducted by researchers showed that the emergence of periodontal disease in Malang City from January to September 2019 accounted for 2759 cases with details of 1674 women and 1085 men affecting age groups from the highest prevalence in those to 45–64 years, then 35–44 years, and finally 19–34 years old. Gingivitis and periodontitis are clinical manifestations of periodontal disease.4 Etiologically, the main cause of periodontal disease is the accumulation of plaque.5 Periodontal disease is characterized by dysregulation of the resolution pathway of inflammation due to the failure of healing from chronic, progressive, and destructive inflammation that is not resolved in the tooth supporting tissues and triggered by a vulnerable immune system.6

Damage to tooth-supporting tissue due to the severity of periodontal disease is a major cause of tooth loss in adults and the elderly, impacting their self-esteem and reducing their quality of life.7 This is consistent with the statement of Cheng et al. that tooth loss affects the quality of life and influences food selection, diet, nutritional intake and esthetics.8 Although the main cause of periodontal disease is plaque, the risk factors affecting it are numerous.9 Periodontal disease risk factors are divided into two, namely those that can be modified and those that cannot be modified.10 Genetics, age, sex/gender, ethnicity, and osteoporosis are included in the risk factors that cannot be modified.11 While diabetes mellitus, obesity, cardiovascular disease, smoking, alcohol consumption, poor oral hygiene, hormonal changes in women, sedentary lifestyle, nutritional intake, stress, treatment, systemic inflammation, adipocytokine dysregulation, and viral infections are included in the risk factors that can be modified.12

Smoking is included as one of the risk factors for periodontal disease because exposure to tobacco smoke can cause changes in the oral microbiota.13 The microbiota of the mouth is believed to have an important role in protecting the oral cavity from disease development.14 Several epidemiological studies show that periodontal disease is more common in smokers than nonsmokers.15,16 Besides smoking, risk factors for periodontal disease include individual consumption patterns.17 A balanced diet has an important role in maintaining periodontal health, where bone formation and regeneration is influenced by nutritional intake of both macronutrients and micronutrients.9 Another factor that influences periodontal disease is the presence of systemic disease. Systemic disease and periodontal disease have a two-way relationship, where periodontal disease can worsen systemic conditions, and some systemic diseases can cause periodontal disease.18 Based on these facts, the researchers want to determine their effects on periodontal disease, namely the risk factors smoking habits, consumption patterns, and systemic diseases among the 19–64 age group in Malang City.

MethodsThis study uses a non-experimental quantitative analytic research design with a cross sectional study approach. This research was conducted at all Community Health Centers, or Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat (Puskesmas), of Malang City. This study was conducted from December 2019 to February 2020. The population of this study included all the patients who had visited the dental clinics in The Community Health Centers (Puskesmas) of Malang City from December 2019 to February 2020, resulting in a total population of 1913 persons. The cluster random sampling technique was used so that five selected Puskesmas. The inclusion criteria were patients aged 19–64 who visited the Puskesmas dental clinics located in Malang from December 2019 to February 2020. The patients were Malang City natives that were not in the process of reducing or increasing caloric intake and were willing to become research respondents as evidenced by their completion of informed consent forms. The exclusion criteria included patients who did not fully complete the questionnaire, patients with tooth extractions, and patients who had filled out the questionnaire, but were canceled for the examination.

Data collection techniques in this study were carried out by collecting primary and secondary data. Primary data collection was done to obtain information on smoking habits, consumption patterns, and history of systemic disease. This information was obtained from respondents through interviews using a validated questionnaire. The questionnaire used by researchers was adopted from the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) to obtain information about the respondents’ frequency of qualitative eating, which consisted of a column of food lists and frequency categories. The list of foods made by researchers was classified into each nutrient and adjusted to the food habits/food availability of the local community. The categorization of the FFQ questionnaire in this study was divided into three, namely “over”, “enough”, and “less”. Calculation and categorization of the range of scores was done by calculating the results of calculations based on the analysis of the maximum score, minimum score, range, class, and interval for each nutrient. In this study, the categorization was merged for the purpose of the bivariate tests to minimize the difference in result scores for the research data that is outstanding. Secondary data collection obtained from dental examination medical records was also used to determine the diagnosis from doctors about the periodontal disease in the selected patients based on ICD X in code K.05. Data analysis in this study was done through several methods: multivariate analyses use logistic regression.

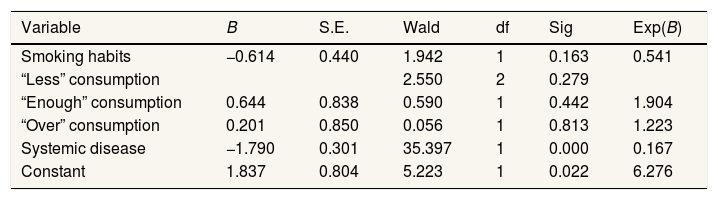

ResultBased on the test results of the logistic regression model (Table 1), a constant coefficient of 1.837 shows that without using the independent variable, the predictive tendency of the logistic regression model is positive while the coefficient of smoking habit is −0.614.It indicates that non-smoking respondents did not experience periodontal disease. The coefficient of the variable for the “enough” level of consumption patterns obtained a value of 0.644, which indicates that respondents with “enough” level of consumption patterns have periodontal disease. Respondents scoring at the “over” level for consumption patterns had a variable coefficient of 0.201, which means that respondents with “over” consumption patterns experience periodontal disease. The coefficient of variables for systemic diseases is −1.790, which indicates that respondents who did not have a systemic disease condition did not experience periodontal disease.

Logistic regression model test results.

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking habits | −0.614 | 0.440 | 1.942 | 1 | 0.163 | 0.541 |

| “Less” consumption | 2.550 | 2 | 0.279 | |||

| “Enough” consumption | 0.644 | 0.838 | 0.590 | 1 | 0.442 | 1.904 |

| “Over” consumption | 0.201 | 0.850 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.813 | 1.223 |

| Systemic disease | −1.790 | 0.301 | 35.397 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.167 |

| Constant | 1.837 | 0.804 | 5.223 | 1 | 0.022 | 6.276 |

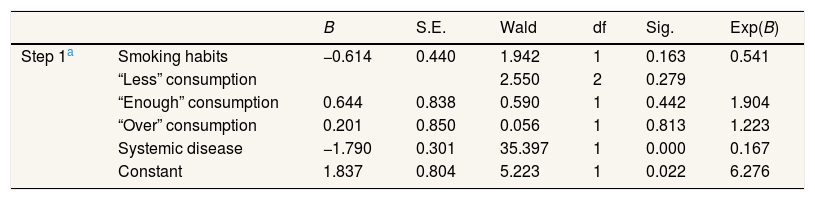

The results of the partial effect test using the Wald test on the logistic regression model between smoking habits, consumption patterns, and systemic disease on periodontal disease were obtained and inferred as these four findings: (1) there was no significant effect between smoking habit on periodontal disease (Wald's value of 1.942 with a significance value of 0.163 (p>0.05); (2) there was no significant effect between the “enough” level of consumption patterns on periodontal disease (Wald's value of 0.590 with a significance value of 0.442 (p>0.05); (3) there was no significant effect between the “over” level of consumption patterns on periodontal disease (Wald value of 0.056 with a significance value of 0.813 (p>0.05); and (4) there is a significant influence between systemic disease on periodontal disease (Wald's value of 35.397 with a significance value of 0.000 (p<0.05). The comprehensive calculation of Wald's test results on the findings can be seen in Table 2.

Partial effect test results (Wald test).

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1a | Smoking habits | −0.614 | 0.440 | 1.942 | 1 | 0.163 | 0.541 |

| “Less” consumption | 2.550 | 2 | 0.279 | ||||

| “Enough” consumption | 0.644 | 0.838 | 0.590 | 1 | 0.442 | 1.904 | |

| “Over” consumption | 0.201 | 0.850 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.813 | 1.223 | |

| Systemic disease | −1.790 | 0.301 | 35.397 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.167 | |

| Constant | 1.837 | 0.804 | 5.223 | 1 | 0.022 | 6.276 |

Smoking is believed to be one of the riskiest factors in the development and progression of periodontal disease.16 The risk of periodontal disease in smokers proportionally increases 5–15 times with the duration and number of cigarettes smoked.19 In addition, smokers were found to experience more gingival recession, pocket depth, and periodontal tissue damage16. The statement is in accordance with research conducted by Waszkiewicz et al., which concluded that smokers have worse health conditions than nonsmokers.20 The smokers show an increase in the number of bacteria in the mouth.11

Smoking disrupts the balance of periodontal health through three pathways, namely microcirculatory and immune system, connective tissue, and bone metabolism.21 There are mechanisms of how smoking can affect microbes, including through increased saliva acidity, reduced oxygen, the effect of antibiotics, the affect of bacterial adherence to the mucosal surface, and interference with immunity.22 Smoking can affect neutrophil function, which is the main source of matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8). MMP-8 is a key biomarker in chronic periodontitis where the increased level indicates the severity of periodontal inflammation. MMP-8 levels were found to be higher in smokers than nonsmokers.16 In addition, smoking can also reduce the antioxidants in saliva which can prevent free radicals, increasing susceptibility to periodontal disease.23

Consumption patterns have an important role in maintaining periodontal health.24 High consumption of carbohydrates can cause dental caries and periodontal disease through colonization of microorganisms that ferment sugars and produce acids that can damage tooth structure.25 Carbohydrates are classified into three types, namely mono/di-saccharides (sugars), oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides. However, research on human responses to carbohydrates is focused on sugars that produce sweetness.26 Sucrose is the most cariogenic form of sugar when compared to fructose, maltose, and lactose.25 In addition to sucrose, starch-containing foods can also reduce the pH to 5.5, which enters a critical pH for demineralization of enamel.25

Besides carbohydrates, other micronutrients having a significant role in maintaining oral health are minerals and antioxidants. Mineral deficiencies can have an impact on periodontal disease.9 Some minerals have different functions in maintaining oral health homeostasis. Calcium is needed by the body during the process of forming teeth and bones and increasing osseointegration. Magnesium is needed for cell metabolism and increases the rate of healing of periodontal disease. Iron and zinc act as antioxidants and an iron deficiency increases oxidative stress. Fluoride can strengthen enamel, prevent dental caries, and has an anti-bacterial effect.27

Systemic diseases as health risk factors such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and pregnancy are also related to periodontal disease.9 The regression equation model in this study shows that respondents who do not have systemic disease do not experience periodontal disease. The results of the Chi-square test and the Wald test showed that there was a significant relationship and influence between systemic disease and periodontal disease. Systemic disease and periodontal disease do have a two-way relationship, where periodontal disease can worsen systemic conditions, and some systemic diseases can cause periodontal disease.18 Poor oral health increases systemic inflammation, causing an overly aggressive local immune response that has implications for systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease.8 Systemic disorders can result in oral changes of microbiota through the release of poisons or leakage of microbes into the bloodstream.11,28 Moderate periodontal disease increases the level of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a pro-inflammatory agent that is closely related to cardiovascular disease, compared to moderate periodontal and without periodontal disease. In addition to IL-6, periodontal disease is also closely associated with C-reactive protein (CRP) which is a predictor of vascular disease including myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, and sudden cardiac death.29 Patients with periodontal pathogens have higher systemic inflammatory markers such as CRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen than patients without periodontal pathogens. The spread of this systemic organism or its products can stimulate bacteremia or endotoxemia that affect the increase in inflammatory status and stimulate an increase in serum markers of inflammation.18 People with periodontal disease have a 1.14 higher risk of having cardiovascular disease. Periodontitis is also found in 58% of diabetic patients.28 The role of diabetes in periodontal disease is also bidirectional, where diabetes is known as a risk factor for periodontitis and periodontitis itself can affect glycemic control in diabetics.18,28 This remains to be determined whether specific periodontal pathogens stimulate the development of systemic diseases or systemic diseases cause periodontal pathogens to change.28

ConclusionSmoking habits, consumption patterns, and systemic diseases together affect periodontal disease. These three risk factors have a role in affecting the balance of microbiota of the mouth. However, an insignificant relationship was found between smoking habits and consumption patterns on periodontal disease. The study findings also suggest a significant relationship between systemic disease and periodontal disease.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.