To explore the trends in hospitalisations and referrals to a psychiatrist among 0- to 30-year-olds with a pre-existing mental disorder between 2019 and 2022.

MethodWe conducted an observational study of psychiatric hospitalisations and referrals from primary care to psychiatric services in the Basque Country population aged 0-30 years with a previously recorded mental disorder, from 2019 to 2022. Logistic regression models were used to assess the effects of calendar year (2019–2022), gender, age, psychiatric comorbidity and socioeconomic status.

ResultsOf the 608,984 individuals in 2019, 97,962 had a mental health diagnosis. Of these individuals, 0.77% were admitted to a psychiatric ward, while 9.44% were referred to a psychiatrist. Overall, there was a decrease in hospitalisations among patients in 2020, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.89 (confidence interval [CI]: 0.79-0.99), followed by increases in 2021 (OR: 1.22; CI: 1.10-1.36) and 2022 (OR: 1.29; CI: 1.16-1.43). The clusters with the greatest increases in hospitalisations were self-harm and anxiety. Total referrals to specialist services did not show significant changes. Patients with a low to middle socioeconomic status were more likely to decompensate. Psychiatric comorbidity was the main cause of decompensation, with an OR >40.

ConclusionsThe change in trend on mental health decompensation was more evident in hospital-based care than in community care. The high decompensation rate in people with psychiatric comorbidities indicates a deterioration in clinical course, suggesting the need for more intensive monitoring.

Analizar las tendencias en hospitalizaciones psiquiátricas y derivaciones de personas de entre 0 y 30 años con un trastorno mental preexistente entre 2019 y 2022.

MétodoEstudio observacional de hospitalizaciones psiquiátricas y de derivaciones desde atención primaria a consultas de psiquiatría de la población del País Vasco de entre 0 y 30 años con un trastorno mental previo. Se utilizaron modelos de regresión logística para evaluar el efecto del año natural (2019-2022), el sexo, la edad, la comorbilidad psiquiátrica y el estatus socioeconómico.

ResultadosEn 2019, de 608.984 personas, 97.962 tenían un diagnóstico de salud mental. De estas, el 0,77% fueron ingresadas en una unidad de psiquiatría, mientras que el 9,44% fueron derivadas a un psiquiatra. Las hospitalizaciones disminuyeron en 2020, con una odds ratio (OR) de 0,89 (intervalo de confianza [IC]: 0,79-0,99), y aumentaron en 2021 (OR: 1,22; IC: 1,10-1,36) y 2022 (OR: 1,29; IC: 1,16-1,43). Los mayores aumentos en las hospitalizaciones fueron por autolesiones y ansiedad. Las derivaciones a consultas especializadas no mostraron cambios significativos. Los pacientes de nivel socioeconómico bajo o medio sufrieron más descompensaciones. La comorbilidad psiquiátrica fue la principal causa de descompensación, con una OR>40.

ConclusionesLa tendencia en el cambio del curso clínico fue más evidente en la atención hospitalaria que en la comunitaria. La elevada tasa de descompensación en las personas con comorbilidad psiquiátrica indica un deterioro clínico y sugiere la necesidad de mayor monitorización.

Expert reports indicate that the mental health of children, adolescents and young people has deteriorated in recent years.1,2 This trend can be measured in the general population using incidence rates among individuals who were previously without a mental disorder3 or using indicators showing a change in the use of psychiatric resources among individuals who were previously diagnosed with a mental disorder.4,5 In a Beveridge-type healthcare system6, such as the Spanish system, it may manifest as a referral from primary care to psychiatry or as hospitalization.5,7 In 2020, the most notable development in the use of mental health resources was a decrease in psychiatric consultations and hospitalisations.8 Although limited access to health services during the pandemic reduced the recorded incidence of new cases in 2020, these negative conditions led to a rebound effect in 2021 and 2022. Furthermore, it has been noted that patients with a mental disorder decompensated more frequently, resulting in a higher rate of hospitalisations in subsequent years;9 however, most studies have been based on hospital clusters,7,10 with only a few using population-level data.8,11 Generally, previous research has compared the pandemic period with previous years.7,12 The analysis of decompensation trends should incorporate psychiatric comorbidities, given their role in patient evolution.13 However, there is a lack of studies addressing this issue.1

Health inequalities, which are defined as systematic and unfair differences in health outcomes and their determinants within a population, have worsened in recent years.14 It is known that socioeconomic status and gender not only determine the risk of mental disorder in young people and adolescents, but also inequity in mental health care.15,16 As the impact of the pandemic was worse for structurally marginalised groups,17 it is reasonable to suppose that these groups experienced poorer mental health care as a result.18 This increased need should have resulted in greater demand for mental health referrals from primary care and psychiatric hospitalisations among children, adolescents and young adults. In light of the lack of population studies in Spain, studies measuring changes in resource use before, during and after the pandemic are required in order to ascertain whether mental health services in the post-pandemic era are addressing possible inequalities relating to age, comorbidity, sex and socioeconomic status.19

This study aimed to explore trends in psychiatric hospitalisations and referrals for psychiatric consultations among individuals aged 0–30 years with a pre-existing mental disorder, categorised by mental disorder cluster, socioeconomic status, psychiatric comorbidity, sex and age, between 2019 and 2022.

MethodDesignWe conducted a retrospective, population-based, observational study to assess two indicators of change in clinical course: psychiatric hospitalisations and referrals to psychiatric services (see supplementary material for the full version of the methods section). We analysed these indicators each year from 2019 to 2022 in the Basque population. The pre-pandemic situation was represented by 2019; the pandemic situation by 2020 and 2021, when the strictest measures restricting social interaction were in place; and the situation after the pandemic's peak by 2022. Data were obtained from the institutional database of the Basque Health Service (Oracle Analytics Server), which contains anonymised administrative and clinical records of the Basque population from 1 January 2003 to the present day. The study protocol was approved on 22 May 2023 by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Basque Country (reference number PI2023037).

Population and variablesAll individuals aged 0–30 on 1 January each year (2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022) were analysed. First, all mental health diagnoses recorded in this population in primary care, emergency, outpatient and inpatient settings were considered. Data were also collected on other sociodemographic variables, including sex, age and socioeconomic status. These diagnoses were then aggregated into eight clusters: anxiety (including anxiety, acute stress reactions and coping reactions), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorders, depression (including depression and bipolar disorder), substance use, psychosis and personality disorders, eating disorders, and self-harm16 (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material for the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] 9 and ICD-10 codes used).

To assess socioeconomic status, we considered household income as reflected by each individual's medication co-payment category. In Spain, drug co-payment categories are determined based on the income of the designated parent. In this classification, high socioeconomic status corresponded to households with annual incomes greater than or equal to €18,000, and a middle category to those with annual incomes below this threshold but who still contributed to medication costs, while low socioeconomic status indicated people at risk of exclusion, corresponding to households where the head of the household was exempt from co-payment.15

The American Psychological Association defines decompensation as a breakdown in an individual's defence mechanisms resulting in progressive loss of functioning or worsening of psychiatric symptoms.20 However, the thorough clinical assessment required to measure this is not available in the Basque administrative and clinical database. Therefore, we used hospitalisations and referrals as indicators, or proxies, of the change in clinical course. Individuals aged 0 to 30 years were included in one of the eight clusters of diagnoses on 1 January each year according to the specified codes (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Firstly, it was determined whether they had been admitted to psychiatric services at least once during the year. Secondly, it was checked whether they had been referred from primary care to a psychiatrist in this period. Records of hospitalisations and referrals were obtained from the Oracle Analytics Server. As the objective was to evaluate the risk of change in clinical course in individuals with mental health conditions, the outcome variables of interest were whether each individual in the population had experienced a psychiatric admission or been referred for psychiatric care at least once in a given year. Therefore, readmissions and repeat referrals were not counted.

Statistical analysisLogistic regression models were used to assess the association of calendar year (2019–2022), gender, age and socioeconomic status on the probability of psychiatric hospitalisation and referral from primary care to specialist psychiatry. Given the descriptive nature of the study, the logistic regression models should be understood as statistical adjustment and summarisation tools, rather than as predictive or causal models21. Statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 4.3.2). All parameters were estimated along with their 95% confidence intervals (95CI).

Ethical considerationsThis study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval on 22 May 2023 from the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of Euskadi (study code PI2023037) which waived the requirement for informed consent as all data were anonymized.

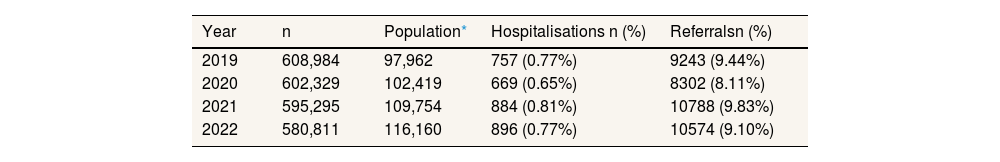

ResultsTable 1 shows the total population aged 0–30 years, as well as the subpopulation with a previous diagnosis of mental disorder, for the years 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. In 2019, the total population was 608,984, of whom 97,962 had a mental health diagnosis. Of these individuals, 757 (0.77%) were admitted to a psychiatric ward and 9243 (9.44%) were referred to a psychiatrist from a primary care setting.

New hospitalisations and referrals per year for the population with a pre-existing mental health diagnosis.

| Year | n | Population* | Hospitalisations n (%) | Referralsn (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 608,984 | 97,962 | 757 (0.77%) | 9243 (9.44%) |

| 2020 | 602,329 | 102,419 | 669 (0.65%) | 8302 (8.11%) |

| 2021 | 595,295 | 109,754 | 884 (0.81%) | 10788 (9.83%) |

| 2022 | 580,811 | 116,160 | 896 (0.77%) | 10574 (9.10%) |

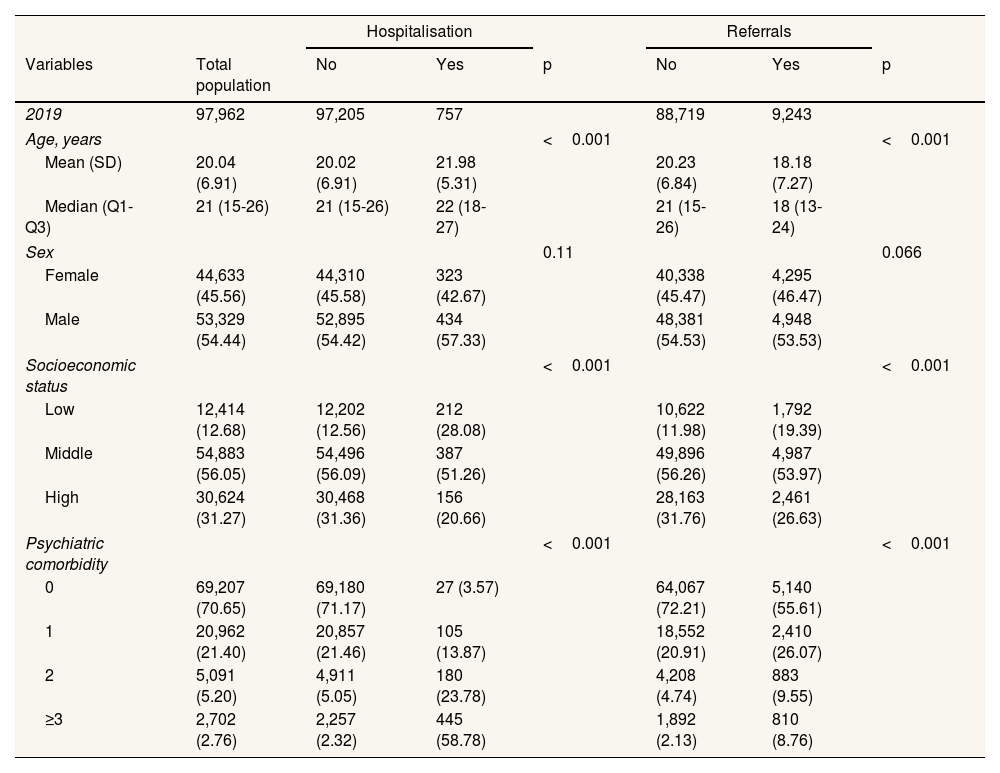

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the population with a mental disorder who had a psychiatric admission or were referred to a psychiatrist in 2019. Statistically significant differences were observed in age and socioeconomic status between patients who decompensated (were hospitalised and/or referred to mental health services) and those who did not. The percentage of individuals with hospitalisations and primary care mental health referrals was higher in the low socioeconomic status group. Those hospitalised were, on average, 1.96 years older than those not hospitalised, while those referred were, on average, 2.05 years younger. Comorbidity significantly increased the risk of decompensation, with the group of patients with ≥3 comorbidities containing 2.76% of all patients and accounting for 58.78% of hospitalisations and 8.76% of referrals. The characteristics are broken down by pre-pandemic cluster in 2019 in Tables S2 and S3 in Supplementary Material, for hospitalisations and referrals, respectively.

Characteristics of the total population with a pre-existing mental disorder overall and stratified by psychiatric hospitalisation and referral to community psychiatry in 2019.

| Hospitalisation | Referrals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total population | No | Yes | p | No | Yes | p |

| 2019 | 97,962 | 97,205 | 757 | 88,719 | 9,243 | ||

| Age, years | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.04 (6.91) | 20.02 (6.91) | 21.98 (5.31) | 20.23 (6.84) | 18.18 (7.27) | ||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 21 (15-26) | 21 (15-26) | 22 (18-27) | 21 (15-26) | 18 (13-24) | ||

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.066 | |||||

| Female | 44,633 (45.56) | 44,310 (45.58) | 323 (42.67) | 40,338 (45.47) | 4,295 (46.47) | ||

| Male | 53,329 (54.44) | 52,895 (54.42) | 434 (57.33) | 48,381 (54.53) | 4,948 (53.53) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 12,414 (12.68) | 12,202 (12.56) | 212 (28.08) | 10,622 (11.98) | 1,792 (19.39) | ||

| Middle | 54,883 (56.05) | 54,496 (56.09) | 387 (51.26) | 49,896 (56.26) | 4,987 (53.97) | ||

| High | 30,624 (31.27) | 30,468 (31.36) | 156 (20.66) | 28,163 (31.76) | 2,461 (26.63) | ||

| Psychiatric comorbidity | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 69,207 (70.65) | 69,180 (71.17) | 27 (3.57) | 64,067 (72.21) | 5,140 (55.61) | ||

| 1 | 20,962 (21.40) | 20,857 (21.46) | 105 (13.87) | 18,552 (20.91) | 2,410 (26.07) | ||

| 2 | 5,091 (5.20) | 4,911 (5.05) | 180 (23.78) | 4,208 (4.74) | 883 (9.55) | ||

| ≥3 | 2,702 (2.76) | 2,257 (2.32) | 445 (58.78) | 1,892 (2.13) | 810 (8.76) | ||

SD: standard deviation; Q: quintile.

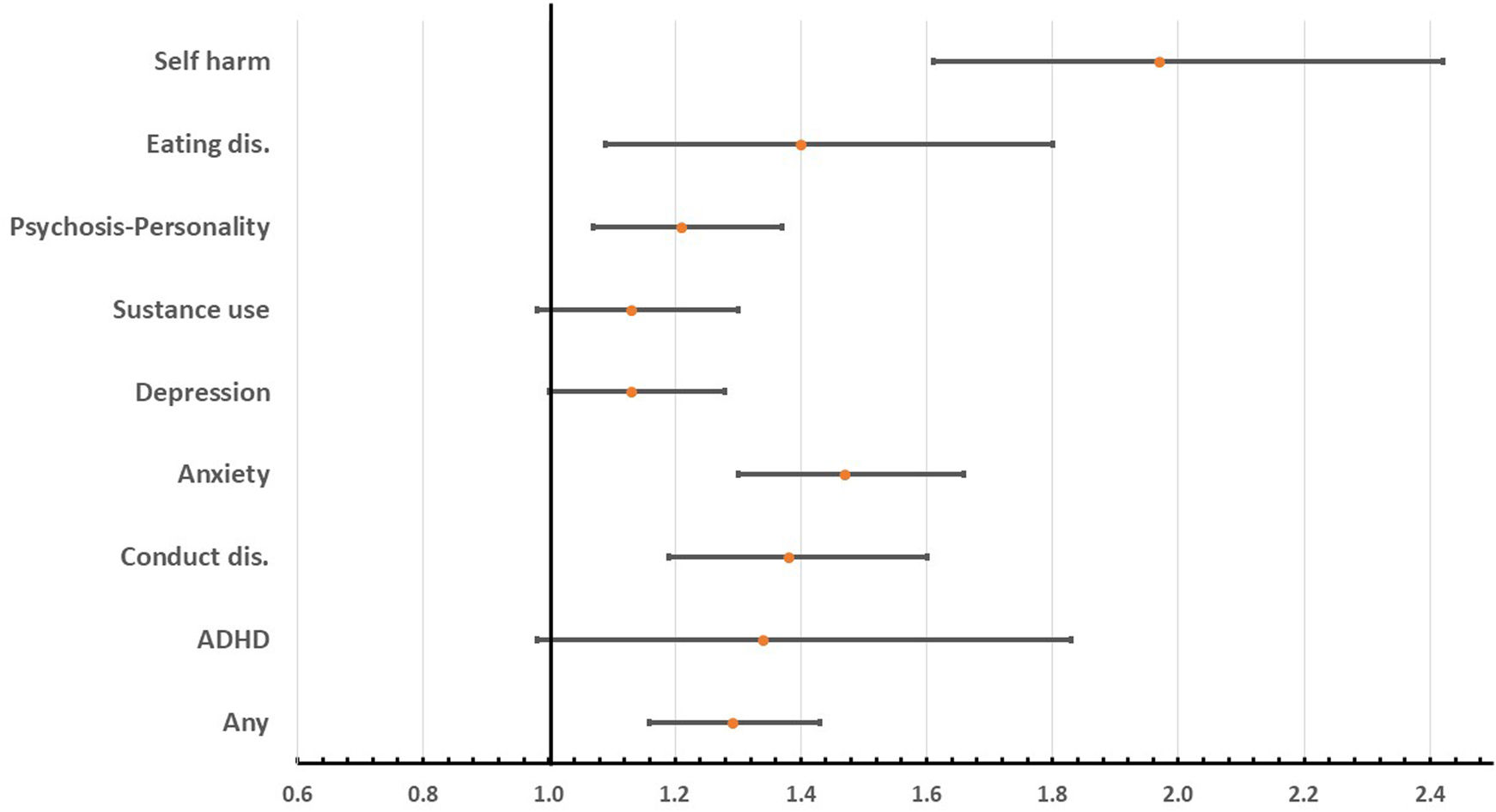

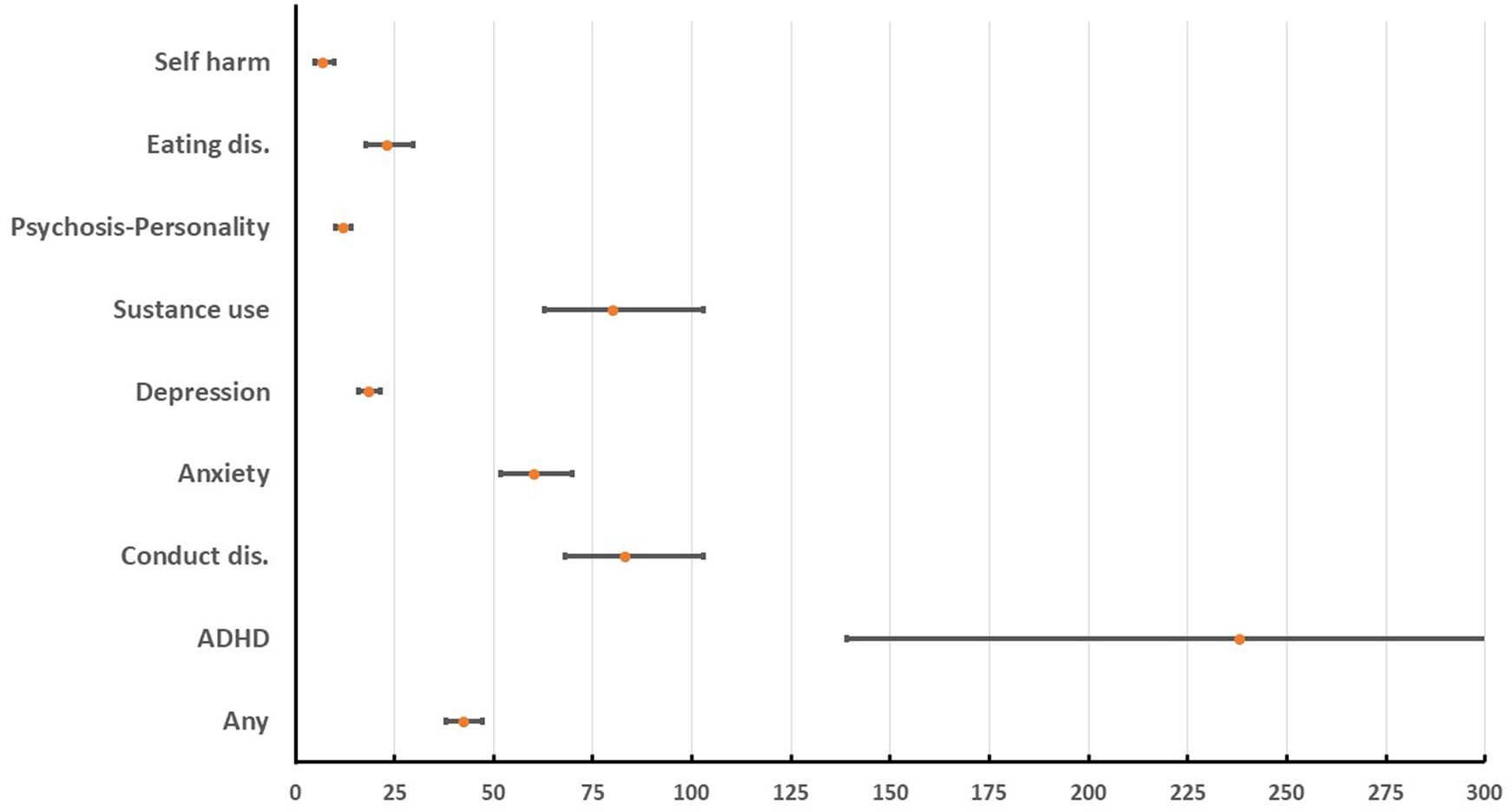

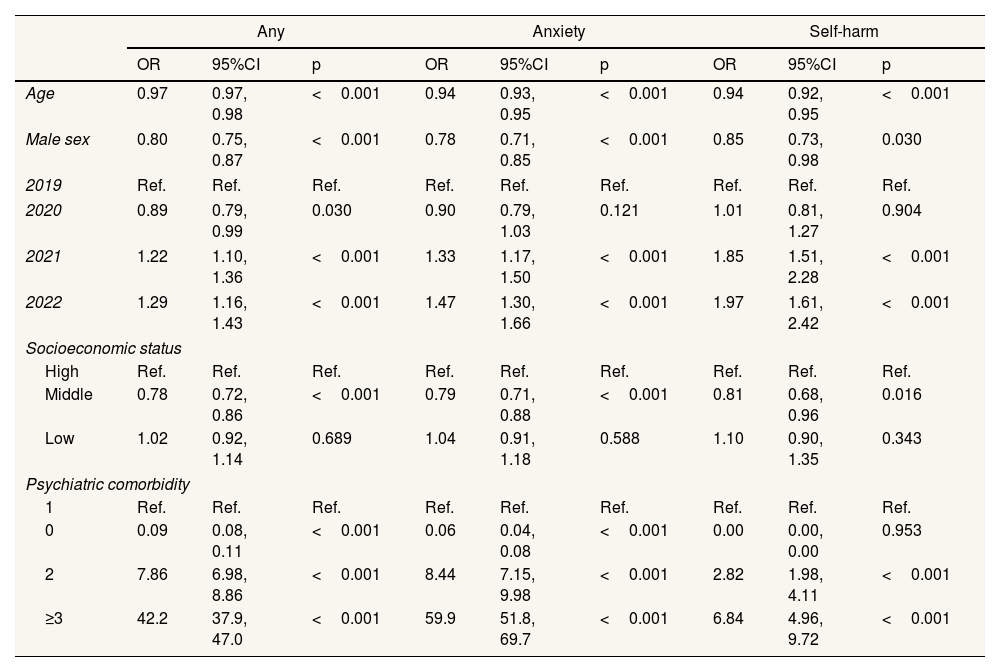

The likelihood of hospitalisation was assessed using logistic regression analysis in each cluster of mental disorders (see Table S4 in Supplementary Material). In 2020, there was a reduction in the risk of hospitalisation that was statistically significant overall, although not in all clusters. By contrast, there were widespread increases in 2021 and 2022, with different odds ratios (OR) whose 95%CI included 1 in several clusters. Figure 1 shows a forest plot summarising these models, comparing OR and their 95%CI by cluster in 2022 with the 2019 baseline values, adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status and comorbidity. Table 3 shows the full models for the group with any mental disorder, as well as for the anxiety and self-harm clusters, in which the association of the pandemic was most pronounced. In 2021, the self-harm cluster had an OR of 1.85 (95CI: 1.51-2.28), rising to 1.97 (95CI: 1.61-2.42) in 2022. The OR was significant in the anxiety cluster in both 2021 (OR: 1.33; 95CI: 1.17-1.50) and 2022 (OR: 1.47; 95CI: 1.30-1.66). In the substance use cluster, the changes in 2021 and 2022 were not significant. Also noteworthy in these tables is the substantial association of comorbidity, with an OR of 42.2 (95CI: 37.9-47.0) across all clusters. Figure 2, a forest plot of the OR and their 95CI, illustrates this finding.

Logistic regressions of the likelihood of hospitalisation in the entire population with a mental disorder and in the clusters with anxiety and self-harm.

| Any | Anxiety | Self-harm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.97, 0.98 | <0.001 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 | <0.001 | 0.94 | 0.92, 0.95 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 0.80 | 0.75, 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.71, 0.85 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.73, 0.98 | 0.030 |

| 2019 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2020 | 0.89 | 0.79, 0.99 | 0.030 | 0.90 | 0.79, 1.03 | 0.121 | 1.01 | 0.81, 1.27 | 0.904 |

| 2021 | 1.22 | 1.10, 1.36 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 1.17, 1.50 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 1.51, 2.28 | <0.001 |

| 2022 | 1.29 | 1.16, 1.43 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 1.30, 1.66 | <0.001 | 1.97 | 1.61, 2.42 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||||

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Middle | 0.78 | 0.72, 0.86 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.71, 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.68, 0.96 | 0.016 |

| Low | 1.02 | 0.92, 1.14 | 0.689 | 1.04 | 0.91, 1.18 | 0.588 | 1.10 | 0.90, 1.35 | 0.343 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | |||||||||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 0 | 0.09 | 0.08, 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.04, 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 0.953 |

| 2 | 7.86 | 6.98, 8.86 | <0.001 | 8.44 | 7.15, 9.98 | <0.001 | 2.82 | 1.98, 4.11 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 42.2 | 37.9, 47.0 | <0.001 | 59.9 | 51.8, 69.7 | <0.001 | 6.84 | 4.96, 9.72 | <0.001 |

OR: odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

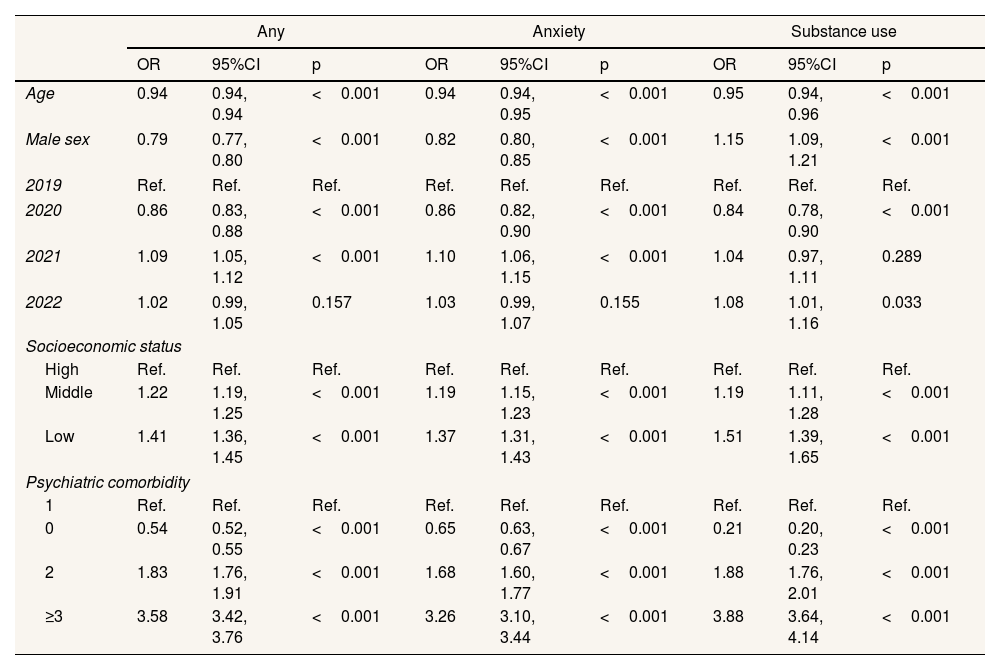

Table 4 and Table S5 in Supplementary Material show the results of all the logistic regression models that analysed the likelihood of a mental health referral, disaggregated across all clusters. Due to their ability to organise and summarise the trend in hospitalisations and referrals over the years analysed, the OR derived from these logistic regression models should be understood as descriptive statistics, rather than as predictions or evidence of causality. Figure S1 in Supplementary Material provides a clear visualisation of the results by showing the forest plot comparing 2022 with 2019 (baseline). This comparison is adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status and comorbidity. A rebound effect, characterised by the highest probability of referral, was apparent in the clusters relating to ADHD, self-harm and substance use, but not in the other clusters or overall. There was a statistically significant decrease in referrals among patients with a mental disorder in 2020, with an OR of 0.86 (95CI: 0.83-0.88), followed by an increase in 2021, with an OR of 1.09 (95CI: 1.05-1.12). In 2022, however, the differences were not significant. Patients with a mental disorder from a low or middle socioeconomic status background were more likely to be referred, with OR of 1.22 (95CI: 1.19-1.25) and 1.41 (95CI: 1.36-1.45), respectively. This higher referral risk in patients with low or middle socioeconomic status is statistically significant in almost all clusters. Comorbidity is also a statistically significant risk factor for referral from primary care, with the OR decreasing by about half in the no comorbidity category relative to the one comorbidity category, and increasing to OR of 2.5 or more in the category with ≥3 comorbidities. Figure S2 in Supplementary Material illustrates this association, which was significant, albeit smaller than that observed for hospitalisations.

Logistic regressions of the likelihood of referral in the entire population with a mental disorder and in the clusters with anxiety and substance use.

| Any | Anxiety | Substance use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Age | 0.94 | 0.94, 0.94 | <0.001 | 0.94 | 0.94, 0.95 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 0.94, 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 0.79 | 0.77, 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.80, 0.85 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 1.09, 1.21 | <0.001 |

| 2019 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2020 | 0.86 | 0.83, 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.86 | 0.82, 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.78, 0.90 | <0.001 |

| 2021 | 1.09 | 1.05, 1.12 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.06, 1.15 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.97, 1.11 | 0.289 |

| 2022 | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.157 | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.07 | 0.155 | 1.08 | 1.01, 1.16 | 0.033 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||||

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Middle | 1.22 | 1.19, 1.25 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.15, 1.23 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.11, 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Low | 1.41 | 1.36, 1.45 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.31, 1.43 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.39, 1.65 | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | |||||||||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 0 | 0.54 | 0.52, 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.63, 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.20, 0.23 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.83 | 1.76, 1.91 | <0.001 | 1.68 | 1.60, 1.77 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.76, 2.01 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 3.58 | 3.42, 3.76 | <0.001 | 3.26 | 3.10, 3.44 | <0.001 | 3.88 | 3.64, 4.14 | <0.001 |

OR: odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

The main finding of this study is that psychiatric comorbidity has an enormous association on the need for mental health hospitalizations in children, adolescents and young adults in the post-pandemic peak era. A gradient according to comorbidity category was observed, describing a profile of young patients with multiple severe disorders and an average age of around 22 years. The group with ≥3 comorbidities represented 2.78% of the total population studied, accounting for 58.78% (445 out of 757 hospitalized cases), which translated into a huge OR of 42.2. Differences in mental health referrals (OR: 3.58; 95CI: 3.42-3.76) suggest that crises in these patients are managed through hospitalisation rather than outpatient care. There are several reasons why the pandemic had a much greater effect on those who were more vulnerable, i.e., those with more psychiatric comorbidities. Firstly, it disrupted the continuity of the outpatient clinical management of psychiatric patients in general.22 Secondly, this group was less resilient to the stress generated by restrictions on social mobility, making them more susceptible to decompensation.23 Thirdly, stigma surrounding mental health issues can hinder sociability and encourage the use of social networks, potentially increasing suicidal and self-harming behaviours among young people.11

The use of mental health resources due to decompensation in adolescents and young patients with a diagnosed mental disorder differed significantly before and after the COVID-19 pandemic as a function of the type of resource used and mental disorder cluster. The risk of hospitalisation increased significantly in 2021 and 2022 compared to 2019, following a decrease in 2020. In contrast, the total number of referrals to psychiatry by primary care physicians remained stable in 2021 and 2022, although they increased in some clusters (self-harm, eating disorders, substance use and ADHD). Two other notable findings are the higher risk of decompensation in low- and middle-socioeconomic status clusters, and in patients with psychiatric comorbidities, especially given the size of this cluster in the general population (2.76%). We hypothesise that the mental health situation continued to deteriorate during the pandemic, amplifying existing trends. Our results suggest that young people with a history of mental disorders experienced more decompensations in response to post-COVID-19 stress, especially those with more severe conditions.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to show that the impact of the pandemic on mental health care was more marked in hospital-based care than in community care. A study measuring the incidence of hospitalisations in the Canadian population aged up to 20 years found similar increases in anxiety and personality disorders, as well as suicide in women, and eating disorders in both sexes, during the period of high SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence, but an overall decrease in mental health hospitalisations between the pre- and pandemic periods.8 Another two time series studies analysing data from French population also found significant increases in post-pandemic psychiatric resource use, including hospitalizations, among young people with a history of mental health issues.11,24 Both studies highlighted the potential role of social media in increasing the risk of decompensation in adolescents and girls due to their greater usage and subsequent higher exposure to interpersonal stress.25 Similarly, our results also indicated a higher risk of hospitalisation among females than males, and among adolescents than young adults. The finding of declining referrals during the peak of the pandemic is consistent with previous literature;26 however, unlike other studies, we did not observe an increase in referrals in the post-peak period of the pandemic.17,27

Notably, the self-harm cluster showed the greatest and most consistent increase in the probability of decompensation in the post-peak years of the pandemic, in terms of both hospitalisations and referrals. This finding is consistent with the 25% increase in suicide attempts in Catalonia between September 2020 and March 2021,28 and the 50% increase in medical emergencies involving suicidal ideation and self-harm in the young US population between 2019 and 2022.29 Another cluster characterised by increased use of resources was eating disorders.

The clusters of psychosis, depression, anxiety and conduct disorders behaved similarly to the overall sample of patients with a history of psychiatric illness in that they showed an increase in hospitalisations but not referrals. Previous studies have also reported increases in acute hospitalisations for psychosis during the pandemic in the British and Australian populations30–32 and in young people in France for any mental disorder.11,17 These results contradict the trend observed over the past 22 years of a general decline in psychiatric hospital activity.33,34

Inequalities in the incidence and prevalence of mental disorders by socioeconomic status in our population have been well documented.15,16 Analysis by socioeconomic status raises the question of why, in the period 2019–2022, people with low socioeconomic status had the same risk of hospitalisation as those with high socioeconomic status, but were more likely to be referred from primary care. On the other hand, statistically significant differences in lower risk were only found for the middle socioeconomic status group for total hospitalisations. One possibility is that the noted inequality is manifested in the incidence rate, but not in the probability of hospitalisation. The explanation for the differences in the detection of decompensation in primary care is simpler. The gradient in referral risk may be due to 20% of the population having dual health coverage (public and private), and people with higher incomes being those who are most likely to take out private insurance and therefore seek treatment from private providers.35 Along similar lines, the lack of data on private sector resource use could mean that our figures underestimate psychiatric hospital admissions. Nevertheless, although private psychiatric consultations are common, there are few private psychiatric hospitals in the Basque Country, and we do not believe that the use of these resources explains our results.

Strengths and limitationsThis study provides indicators for the entire population of individuals under 30 years of age (over 600,000 people) and the care response received in both inpatient and outpatient psychiatric settings. The main limitation of this study is the lack of evidence of causality, that is, whether increased service use implies decompensation. Nonetheless, psychiatric hospitalisation in people under 30 clearly indicates that regular symptoms have worsened and that the patient has lost the ability to cope with life changes and everyday activities and responsibilities. Another limitation is the lack of registration of private psychiatric activity, given that 20% of this population has dual health coverage.35 Another limitation is that diagnostic codes are recorded in different healthcare settings without validation studies. While pathological findings can be used to validate cancer registries, this is not an option for mental health conditions. Nevertheless, each case represents an individual who has sought help from a healthcare provider for a mental health condition. Finally, the pharmaceutical co-payment is only a partial indicator of socioeconomic status, as it only takes one parent's income into account. Strictly speaking, there is no information on the household's overall socioeconomic status level as the database lacks the annual income category of the other parent. On the other hand, however, it showed notable sensitivity in identifying at-risk individuals.

ConclusionsThe increase in hospitalisations following the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates a deterioration in the clinical course of children, adolescents and young adults with a previous mental health diagnosis. While the causes may be directly or indirectly linked to the pandemic, the indicators suggest the need for more intensive monitoring, especially of patients with more psychiatric comorbidity.

Availability of databases and material for replicationThe owner of the data is the Basque Health Service, which maintains a policy of restricted data access for ethical reasons. Our agreement with the Basque Health Service establishes that individual-level data cannot be shared publicly because of confidentiality. Applications for access to the dataset must be made with the approval of the Basque Health Service (https://www.osakidetza.euskadi.eus/servicios-para-profesionales/webosk00-sercon/es/).

The mental health of adolescents and young people has deteriorated in recent years. Key factors in the risk of hospitalization in patients with a pre-existing mental disorder include social determinants, gender and psychiatric comorbidity, as well as the impact of the recent pandemic.

What does this study add to the literature?The risk of hospitalization increased in 2021 and 2022, particularly among those with self-harm or anxiety and a low socioeconomic status. The main cause of decompensation was psychiatric comorbidity.

What are the implications of the results?The high hospitalization rate in people with psychiatric comorbidities indicates a deterioration in clinical course, suggesting that continuity of care should be improved.

Cristina Candal Pedreira.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsL. Mar-Barrutia and A. González-Pinto conceived and designed the research. J. Mar, S. García de Garayo, and M. Gascón obtained the data and carried out the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the methods and results section. L. Mar-Barrutia, A. González-Pinto and J. Mar drafted the manuscript and approved the final version. A. García, J. P. Chart-Pascual and G. Cano-Escalera reviewed the literature, provided text to the introduction and discussion sections of the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version. Further, they all had full access to all the data used in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

We acknowledge the help of Ideas Need Communicating Language Services in improving the use of English in the manuscript.