To construct and validate a questionnaire about the attitude of university students toward health promotion.

MethodA cross-sectional study. A questionnaire of 14 questions was designed and administered to 1486 first-year undergraduates. The principal axes factoring method with oblique rotation was applied and a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. Reliability was calculated through internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha and item-total correlation for the global scale and its subscales.

ResultsA 14-item scale was constructed, with two dimensions. Its Cronbach's alpha was 0.872, and 0.852, and 0.718 for its subscales. The adjustment values of the confirmatory factor analysis were adequate.

ConclusionsThe attitude towards health promotion scale has shown to have adequate psychometric properties. It is an instrument that will help to detect referents and health assets for future interventions.

Construir y validar un cuestionario sobre la actitud de los estudiantes universitarios hacia la promoción de la salud.

MétodoEstudio transversal. Se diseñó un cuestionario de 14 preguntas y se administró a 1486 estudiantes universitarios/as de primer curso. Se aplicó el método de factorización de ejes principales con rotación oblicua y se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio. La fiabilidad se calculó mediante la consistencia interna con el alfa de Cronbach y la correlación ítem-total para la escala global y sus subescalas.

ResultadosSe construyó una escala de 14 ítems con dos dimensiones. Su alfa de Cronbach fue 0,872, y para sus subescalas 0,852 y 0,718. Los valores de ajuste del análisis factorial confirmatorio fueron adecuados.

ConclusionesLa escala de actitud hacia la promoción de la salud ha demostrado tener propiedades psicométricas adecuadas. Es un instrumento que ayudará a detectar referentes y activos de salud para futuras intervenciones.

Health promotion is the main effective process for creating healthy environments and encouraging people to adopt habits towards improving their health and quality of life. International organisations support, through scientific evidence, the positive impact of promotion actions and are clear about the need for intersectoral coordination to raise health standards through community actions.1

Despite this, in countries such as Spain, the low presence of health promotion actions in primary care is denounced2 and the biomedical and paternalistic approach of the health system.3 Community orientation in health care is claimed in a system where intrapersonal and interpersonal theoretical models prevail in health promotion. This would make it possible to overcome the paradoxes of health promotion, understanding health from its collective dimension, as an investment, with person-centred health care, based on health indicators, developed by health professionals.4

On the other side, however, interventions from local administrations, city councils, educational centres, and social centres are becoming increasingly frequent and abundant.5 Therefore, in addition to the desired involvement of health professionals in health promotion strategies, the commitment of workers in other sectors to implement this practice in their professional activity is both necessary and essential. All policies require professionals with competencies for engaging in health promotion in different social and technical areas.6

This requires adequate preparation of professionals in the socio-health system because health is in all policies and the duty to promote health does not only correspond to health professionals.2 From many other sectors, it is necessary to look after people's living conditions, determinants of community health.7

However, the lack of training in community health is seen as one of the main factors in the poor community orientation of the health system.8 All of this has implications for the undergraduate and postgraduate training of these professionals and research invites us to support community training as a key element to reverse this situation.9

In addition to the academic training, scientific development, and social transformation functions attributed to the University, it is also necessary to commit to the continuous development of the personal abilities of the members of the university community and to the improvement of their quality of life. The Network of Health Promoting Universities represents a commitment in this direction10 and its long history is evidence of the positive evolution of the health policies implemented by higher education institutions,11 yet far from a true health promotion culture. To this end, a universalisation of the training of human resources in health promotion and education is essential and should be included in the policies and curricula of all degree programmes, not only those of health sciences.12

It is worth investigating the relationship between health, social, and educational curricula and students’ attitudes towards health promotion.13 Research with health students from different countries conclude that official and hidden curricula strengthen clinical training and reflect the institutional imprint that the programme has had, which could explain the attitude of indifference towards health promotion and the variation in attitudes among students from different universities.14

Starting from the premise that the attitude towards health promotion in health professionals and students is already low, due to their greater inclination towards clinical care and their scarce presence in the health system,15 it is necessary to invest efforts in fostering the acquisition of community competences in undergraduate students.

Attitude as a predisposition, learned, to value or behave in a favourable or unfavourable way towards something or someone16 is one of the essential components for behaviour change, together with knowledge and skill.

Research on health promotion in universities has focused on promoting lifestyles, creating healthy environments, equity, efficiency, efficacy, and effectiveness of university health policies. Among the institutional policies are health education, literacy and communication actions, qualification and professional academic training actions,17 and participatory actions for skills development, leadership, and health awareness in the university community.

However, there are few actions to identify health assets and their role as mediators in the university community, with the current relevance of the health assets model in the strategy of raising community health and participation.9 In this sense, the role of institutional leadership at a high effective level in relation to health promotion in universities is particularly relevant,18 but it is also essential to ensure the participation and leadership of the university community, especially students, in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and greater future professional involvement in community actions.

In this sense, it may be inferred that the identification of students, not only from health sciences degrees, with a positive attitude towards health promotion would be necessary to provide them with competences as health generators. But how to identify them? In addition to the implementation of health assets maps in universities,19 another possible approach to follow would be to actively recruite a university population with an interest in this subject. To do this, a tool would be needed to identify people with a favourable attitude towards promoting the health of the university community. For this population, there are many questionnaires that measure attitudes towards promoting their own health or that identify the factors that favour a better attitude towards healthy practices.20

However, instruments focusing on the assessment of attitudes towards health promotion and prevention activities have been validated in health professionals and are aimed at nursing students.21–23 The analysis of the latter group has led to further work in this area in order to obtain an instrument that can be generally applied to the entire university population, not specifically to students of health sciences degrees, and with a rigorous process that ensures validity and reliability in the university environment. Moreover, the analysis of the reviewed studies justifies the need to create a new questionnaire that improves the psychometric properties and allows it to be applied to the general university population. Hence, the aim of this study was to design and validate a questionnaire to assess the attitude of university students towards health promotion.

MethodDesign of the instrumentFirstly, a search of the scientific literature was carried out in order to locate similar instruments.

The databases searched were WOS, Medline, Scopus, and PsycINFO. The search strategy was: (‘attitude’ OR ‘health attitude’) AND (‘scale’ OR ‘survey’ OR ‘questionnaire’ OR ‘inventory’) AND (‘university students’ OR ‘undergraduates’) AND (‘health promotion’ OR ‘primary prevention’). The terms were searched in both natural language and controlled language, considering their respective thesauri.

The localised questionnaires did not fully conform to the theoretical components proposed by the research team, but they did serve to structure the initial questionnaire and supported the formulation of questions. Questions were generated to be included in a new instrument on Attitude Towards Health Promotion (ATT-HP), which would respond to two fundamental aspects based on the theoretical references of health promotion according to the World Health Organization and the literature identified in the previous search24,25 health promotion assessment and willingness to work with specific health promotion methodologies.

Twenty-six questions were drafted and sent to experts from different disciplines, who were selected according to Jasper's criteria26 in order to assess its construct validity. As a result of this assessment, the final list of questions was reduced to 19, which formed part of the version to be piloted in a sample of 30 students from the nursing and primary education degree programmes at the University of Huelva, Spain, in order to assess comprehension and suitability, and to determine the time invested in answering them.

ParticipantsFor the validation of the instrument, 1486 students were included. As inclusion criteria, they had to be students of the University of Huelva who were in the first year of the following degrees: nursing, primary education, early childhood education, physical activity and sport sciences, psychology, social education, social work, and chemistry. These degrees were chosen because a previous review of their curricula identified subjects related to health promotion.

Data collectionAuthorisation from the deans of the four schools involved was requested to access the centres: School of Nursing, School of Experimental Sciences, School of Education, Psychology and Physical Activity and Sport Sciences, and School of Social Work. First-year teaching staff of the degree programmes involved were contacted to obtain permission to collect data at the beginning or end of the lessons. The questionnaire was administered in person, self-administered and in paper format, during the first two weeks of the academic year. The fieldwork period has been developed during 8 months, from September to May 2021.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics were calculated for the description of the sample (means, standard deviations, frequencies, ranges, and medians). For the descriptive analysis at item level, means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and floor and ceiling effects were determined for each item. The floor and ceiling effects were assessed by establishing a cut-off point of up to 15%.27

For the total questionnaire and for each subscale, reliability was calculated through internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha, considering acceptable scores between 0.70-0.90, the corrected item-test correlations, and Cronbach's alpha when the item had been eliminated.28

In the analysis of the factor structure, the estimation method based on principal axes factoring with oblimin oblique rotation was applied. As for the criterion for assigning items to factors, we have considered those with factor loadings above 0.30, to avoid a relatively weak relationship between the item and the factor.29

For construct validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to reinforce the previous exploratory analysis. For the CFA, the maximum likelihood estimation method was selected for the structural equation model. The following fit indices were calculated, considering the values in brackets as values of a good fit of the model: comparative fit index (CFI > 0.95), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > 0.95), standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR < 0.08), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.06).30 The chi-squared/degree of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) was also calculated, yielding values considered acceptable <2.31 Analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics package, version 25,32 and CFA with IBM SPSS Amos, version 26.32

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Huelva for the review of the protection of human participants or its equivalent. All the participants were informed of the general purpose of the study, as well as of the disadvantages and advantages of their participation.

During these sessions, the students were informed about the aim of the research and the voluntary nature of their participation. Those who agreed to take part were given an informed consent form which they had to sign and return together with the questionnaire. Anonymity, confidentiality, and data processing were maintained at all times in accordance with the provisions of Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights. The data were not used for purposes other than those stated in the objectives of the research. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Huelva, thus ensuring the ethical standards and principles of all research, according to the declaration of Helsinki. The study conforms to the STROBE checklist.

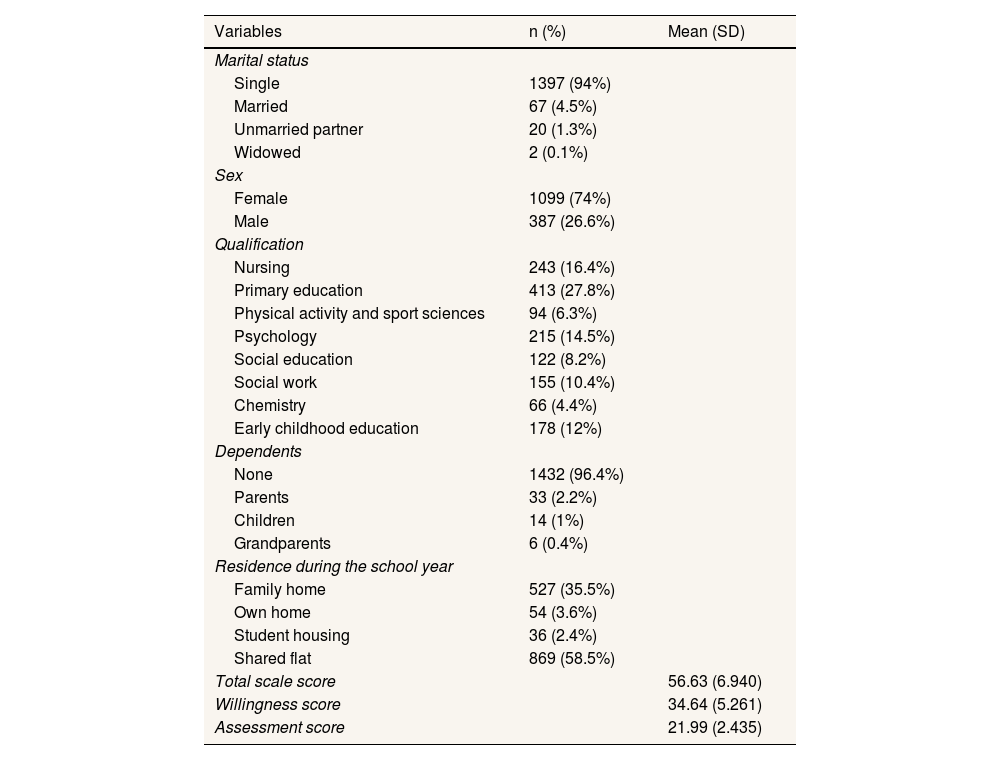

ResultsDescription of the sampleDescriptive information on the study sample is provided in table 1. The questionnaire was answered by 1486 university students, 74% were female, had a mean age of 22.58 years (SD: 11.48), and 94% were single. They came from different educational backgrounds, mainly primary education (27.8%) and nursing (16.4%). 96.4% had no dependents and lived in a flat shared with other students during the academic year (58.5%).

Description of the study sample.

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 1397 (94%) | |

| Married | 67 (4.5%) | |

| Unmarried partner | 20 (1.3%) | |

| Widowed | 2 (0.1%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1099 (74%) | |

| Male | 387 (26.6%) | |

| Qualification | ||

| Nursing | 243 (16.4%) | |

| Primary education | 413 (27.8%) | |

| Physical activity and sport sciences | 94 (6.3%) | |

| Psychology | 215 (14.5%) | |

| Social education | 122 (8.2%) | |

| Social work | 155 (10.4%) | |

| Chemistry | 66 (4.4%) | |

| Early childhood education | 178 (12%) | |

| Dependents | ||

| None | 1432 (96.4%) | |

| Parents | 33 (2.2%) | |

| Children | 14 (1%) | |

| Grandparents | 6 (0.4%) | |

| Residence during the school year | ||

| Family home | 527 (35.5%) | |

| Own home | 54 (3.6%) | |

| Student housing | 36 (2.4%) | |

| Shared flat | 869 (58.5%) | |

| Total scale score | 56.63 (6.940) | |

| Willingness score | 34.64 (5.261) | |

| Assessment score | 21.99 (2.435) | |

SD: standard deviation.

Before analysing the structure of the scale, the 19 initial items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis, which suggested the elimination of five items. These items had a factor loading of less than 0.3. In all cases, it was observed that the content of the item was not essential in the definition of the construct to be analysed.

The removal of these five items resulted in a 14-item scale that was called the ATT-HP scale, structured in two factors: factor 1 (willingness) composed of 9 items; and factor 2 (assessment) composed of 5 items. The response scale for the items followed a 5-point Likert-type scale, formulated in terms of agree/disagree (from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

Based on the questionnaire, it was possible to calculate the total score of the attitude towards health promotion, which ranged from 14 to 70 points, as well as the score for each dimension (factor 1: 9 to 45 points; factor 2: 5 to 25 points). The higher the score, the better the attitude towards health promotion. The scale has been added as supplementary material.

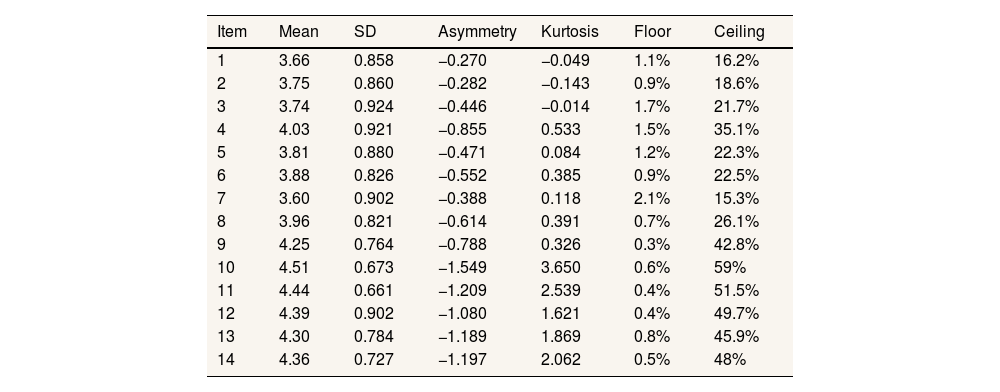

Descriptive analysis at item levelTable 2 shows the descriptive data for each item. Means ranged from 3.60 (item 7) to 4.51 (item 10). All items of the questionnaire showed negative skewness. As for kurtosis, items 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 had a leptokurtic distribution, and items 1, 2 and 3 had a platykurtic distribution.

Description of each item.

| Item | Mean | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | Floor | Ceiling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.66 | 0.858 | −0.270 | −0.049 | 1.1% | 16.2% |

| 2 | 3.75 | 0.860 | −0.282 | −0.143 | 0.9% | 18.6% |

| 3 | 3.74 | 0.924 | −0.446 | −0.014 | 1.7% | 21.7% |

| 4 | 4.03 | 0.921 | −0.855 | 0.533 | 1.5% | 35.1% |

| 5 | 3.81 | 0.880 | −0.471 | 0.084 | 1.2% | 22.3% |

| 6 | 3.88 | 0.826 | −0.552 | 0.385 | 0.9% | 22.5% |

| 7 | 3.60 | 0.902 | −0.388 | 0.118 | 2.1% | 15.3% |

| 8 | 3.96 | 0.821 | −0.614 | 0.391 | 0.7% | 26.1% |

| 9 | 4.25 | 0.764 | −0.788 | 0.326 | 0.3% | 42.8% |

| 10 | 4.51 | 0.673 | −1.549 | 3.650 | 0.6% | 59% |

| 11 | 4.44 | 0.661 | −1.209 | 2.539 | 0.4% | 51.5% |

| 12 | 4.39 | 0.902 | −1.080 | 1.621 | 0.4% | 49.7% |

| 13 | 4.30 | 0.784 | −1.189 | 1.869 | 0.8% | 45.9% |

| 14 | 4.36 | 0.727 | −1.197 | 2.062 | 0.5% | 48% |

SD: standard deviation.

No item showed a floor effect; however, all items showed a ceiling effect. Participants scored item 10 the highest and item 9 the lowest.

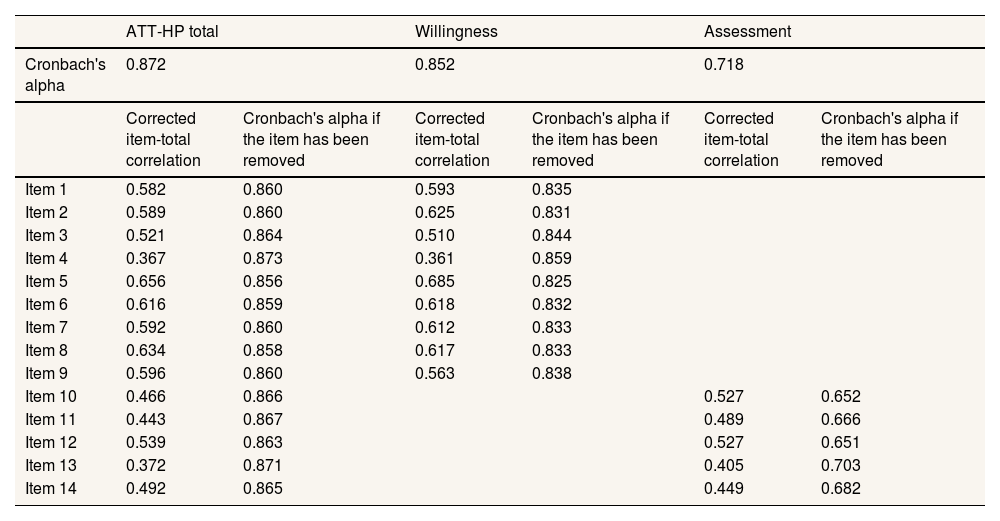

ReliabilityThe internal consistency index with Cronbach's alpha for the scale as a whole was 0.872. For factor 1, it was 0.852, and for factor 2, it was 0.718. For the total scale, if one item was removed, the figures ranged from 0.856 (item 5) to 0.873 (item 4). For the first factor, they ranged from 0.825 (item 5) to 0.859 (item 4), and for the second factor they were between 0.651 (item 12) and 0.703 (item 13).

Table 3 shows the corrected item-test correlations for the overall scale and for each of the dimensions. For the global questionnaire, the corrected item-test correlations ranged from 0.367 (item 4) to 0.596 (item 9). These corrected correlations are between 0.361 (item 4) and 0.685 (item 5) for the factor 1, and between 0.405 (item 13) and 0.527 (items 10 and 12) for factor 2.

Reliability results of the ATT-HP and its subscales.

| ATT-HP total | Willingness | Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach's alpha | 0.872 | 0.852 | 0.718 | |||

| Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach's alpha if the item has been removed | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach's alpha if the item has been removed | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach's alpha if the item has been removed | |

| Item 1 | 0.582 | 0.860 | 0.593 | 0.835 | ||

| Item 2 | 0.589 | 0.860 | 0.625 | 0.831 | ||

| Item 3 | 0.521 | 0.864 | 0.510 | 0.844 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.367 | 0.873 | 0.361 | 0.859 | ||

| Item 5 | 0.656 | 0.856 | 0.685 | 0.825 | ||

| Item 6 | 0.616 | 0.859 | 0.618 | 0.832 | ||

| Item 7 | 0.592 | 0.860 | 0.612 | 0.833 | ||

| Item 8 | 0.634 | 0.858 | 0.617 | 0.833 | ||

| Item 9 | 0.596 | 0.860 | 0.563 | 0.838 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.466 | 0.866 | 0.527 | 0.652 | ||

| Item 11 | 0.443 | 0.867 | 0.489 | 0.666 | ||

| Item 12 | 0.539 | 0.863 | 0.527 | 0.651 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.372 | 0.871 | 0.405 | 0.703 | ||

| Item 14 | 0.492 | 0.865 | 0.449 | 0.682 | ||

ATT-HP: Attitude Towards Health Promotion Scale.

All items, except 4 and 13 (on the total scale), showed correlations above 0.40, with items 5, 6 and 7 showing the highest correlations.

Validity- 1)

Exploratory factor analysis

Bartlett's statistics and KMO tests showed the adequacy of the polychoric correlation matrix to the factor model (x2=6562.858, degrees of freedom=91, p <0.000; KMO=0.915).

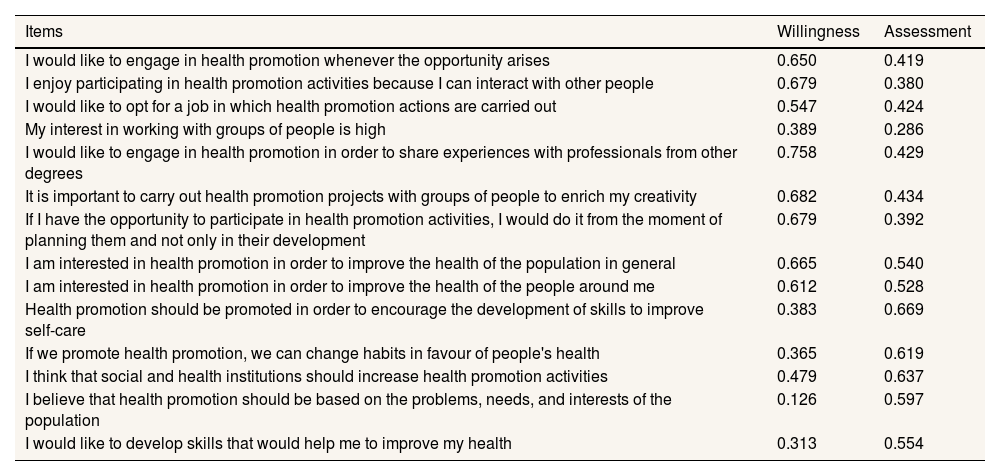

Two factors with eigenvalues >1 were identified, which together explained 48% of the variance (38% for the first factor and 10% for the second). As shown in Table 4, the factor weights suggested a first factor composed of nine items (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) and a second factor composed of five items (10, 11, 12, 13, and 14).

Table 4.Exploratory factor analysis.

Items Willingness Assessment I would like to engage in health promotion whenever the opportunity arises 0.650 0.419 I enjoy participating in health promotion activities because I can interact with other people 0.679 0.380 I would like to opt for a job in which health promotion actions are carried out 0.547 0.424 My interest in working with groups of people is high 0.389 0.286 I would like to engage in health promotion in order to share experiences with professionals from other degrees 0.758 0.429 It is important to carry out health promotion projects with groups of people to enrich my creativity 0.682 0.434 If I have the opportunity to participate in health promotion activities, I would do it from the moment of planning them and not only in their development 0.679 0.392 I am interested in health promotion in order to improve the health of the population in general 0.665 0.540 I am interested in health promotion in order to improve the health of the people around me 0.612 0.528 Health promotion should be promoted in order to encourage the development of skills to improve self-care 0.383 0.669 If we promote health promotion, we can change habits in favour of people's health 0.365 0.619 I think that social and health institutions should increase health promotion activities 0.479 0.637 I believe that health promotion should be based on the problems, needs, and interests of the population 0.126 0.597 I would like to develop skills that would help me to improve my health 0.313 0.554 - 2)

Confirmatory factor analysis

Using CFA, the following results were obtained: x2=306.614, degrees of freedom=71, x2/DF=4.319, TLI=0.954, CFI=0.964, SRMR=0.032 and RMSEA=0.047.

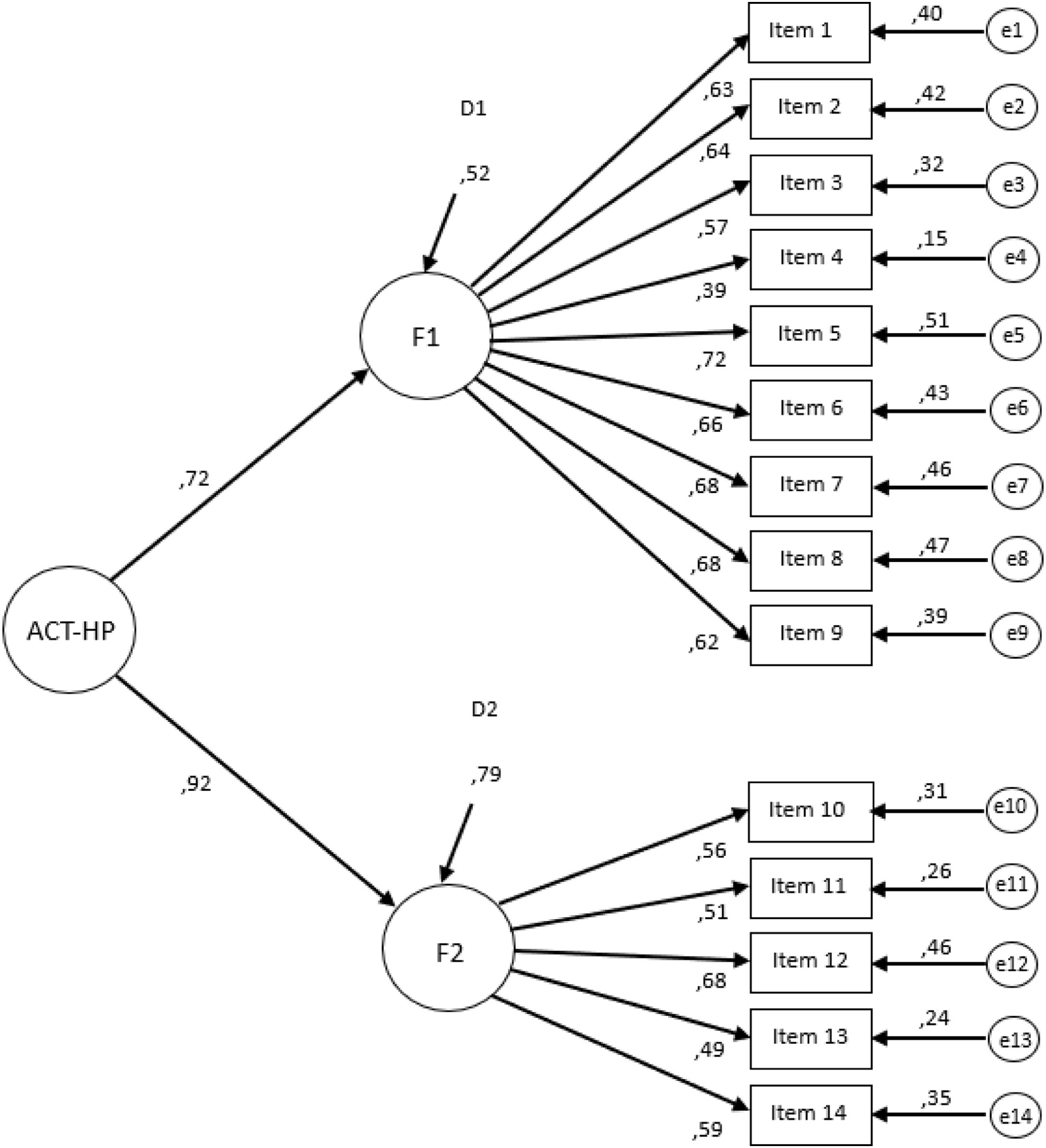

Figure 1 shows the proposed model with two correlated factors. For most items, the standardised factor weights and covariances between the latent variables were ≥0.5.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the ATT-HP Scale. Model with standardised factor weight and residuals. D1 and D2: residual errors for each dimension; e1-e14: residual errors of the observed scores for each item; ATT-HP: Attitude Towards Health Promotion Scale; F1: factor 1 (willingness) of the ATT-HP; F2: factor 2 (assessment) of the ATT-HP.

The aim of this study was to construct and validate a questionnaire to assess the attitude of university students toward health promotion. The results showed that the ATT-HP scale, composed of 14 Likert-type items, presented good psychometric properties, with a structure of two correlated factors for the measurement of attitude towards health promotion. Factor 1 (willingness) assessed the willingness to work with health promotion methodologies and factor 2 (assessment) measured the importance attached to health promotion.

Cronbach's alpha indicators and corrected item-test correlations indicated good internal consistency of the questionnaire, both overall and in each of the two dimensions identified in the factor analysis.

As for the item-test correlations, item 4 for the total scale and for factor 1, and item 13 for the total scale did not reach the score of 0.40, which was suggested as the ideal,33 but they did show good internal consistency when assessed by dimensions, and helped to maintain a high Cronbach's alpha, so it was decided to keep them in the final questionnaire. Regarding the CFA, the proposed model of the questionnaire met the considered values,30,31 showing a good fit. The indices calculated to evaluate the good fit of the CFA model are adequated. However, the chi squared/degree of freedom ratio was 4.319, higher than the criteria (>2) and some items showed a factor loading in the CFA lower than 0.6.

In the literature review, only two instruments focusing on the assessment of attitudes towards health promotion activities were identified.22,23 In both studies, the reference population was Nursing students, which limited the applicability of the instrument. However, the scale in the present study was validated in the general university population, and not exclusively in Health Sciences degrees.

On the other hand, in previous studies, the instruments were validated in samples of less than 250 subjects, whereas in this study the participation was much higher (1486 students). Mooney et al.23 study had broader objectives and only carried out descriptive analyses and correlations. It did not provide psychometric validity data to evaluate it as a suitable instrument for comparison.

Accordingly, Godínez et al.22 was the closest to the proposed objectives, although it did not completely satisfy the theoretical construct proposed by the present research team. The questionnaire validated in the present study has a simpler structure, with only two factors and fewer items (14 as opposed to 21).

The internal consistency of Godínez et al.22 study showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.809 for the total score, and between 0.630 and 0.735 for each subscale. In the study at hand, this value was higher both for the global scale (0.872) and for each dimension (0.852 for factor 1 and 0.718 for factor 2).

The analysis of the reviewed studies20–23 justifies the need to create a new questionnaire that improves the psychometric properties and allows it to be applied to the general university population. The health implications of the attitudes/behaviors relationship must also be taken into account. In this regard, the reasoned action approach to health promotion is very interesting.34 This theory states that the more that is known about the factors involved in compliance or noncompliance with any behavior, the more likely it is that an intervention will be effective and that the degree to which that intention is under attitudinal, normative or self-efficacy control must be determined.

In terms of limitations, given the risk of misunderstanding the questions as it is a self-administered questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted. This was done with a small sample of students and a discussion with experts where difficulties in understanding the message of each item were assessed. Thus, the construct validity of the questionnaire was ensured. Another limitation of this study could be that although the indices calculated to evaluate the good fit of the CFA model are adequate, some values are a bit fair as some items showed a factor loading slightly below 0.6. All items also had a ceiling effect, which can also be considered a limitation of the study. The cultural construction of gender influences people's attitudes and behaviour in any area and has an enormous impact on emotional competences and capacities in the face of the different constructs. This is accentuated in more emotionally charged subjects. It is possible that the attitude towards health promotion may be so, and a separate analysis for both genders could have taken into account the predictive discriminative value of the instrument and prevented the validity of the instrument from being negatively affected.35

The validated model is feasible in terms of ease and speed of completion (3-4 minutes). This makes it highly functional, as it does not reach the recommended maximum of 10-15 minutes.36

It also addresses some methodological gaps related to the insufficient description of the validation process, of the metric analysis used, and/or of the dimensions into which the other questionnaires reviewed were structured. Other advantages offered by the scale include the fact that it is adapted to the specific cultural context, it can be applied in any university course and degree, and that it has been validated in a large sample.

ConclusionsThe results obtained confirm an adequate reliability and validity of the questionnaire. This short and easy to administer questionnaire is useful to identify those people who are positively willing to engage in health promotion efforts. This will help to detect referents and health assets for future interventions in order to promote and maintain the health and wellbeing of the community.

Community interventions in universities must take into account the entire educational community and be supported by instruments that measure not only attitudes, but also actual practices. Therefore, there is a need for future studies to further explore the topic in order to plan and implement interventions that promote greater involvement of students as mediators of health promotion in the university environment.

The ATT-HP scale applied to university students is an instrument that meets the psychometric properties of reliability and internal validity, allowing its use as a research instrument in future studies.

Availability of databases and material for replicationThe authors have decided to make the validated questionnaire available as online online Appendix. As for the availability of the databases, if any researcher needs them, it is possible to contact the corresponding author, who can provide them.

María Errea.

For university population, there are many questionnaires that measure attitudes towards promoting their own health or that identify the factors that favour a better attitude towards healthy practices. However, these have been validated in health professionals and are aimed at Nursing students.

What does this study add to the literature?This scale which was used with university students, satisfies the psychometric criteria for internal validity and reliability, enabling its usage as a research tool in the future.

What are the implications of the results?This questionnaire will assist in the identification of referents and health assets for upcoming actions.

The corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

All authors have made substantial contributions. Conception and design of the study: F.M. García-Padilla and M. Sánchez-Alcón. Collection of data: A. Garrido-Fernández. Analysis and interpretation of the data: E. Sosa-Cordobés and A.M. Ortega-Galán. Writing of the article: A. Garrido-Fernández, E. Sosa-Cordobés and A.M. Ortega-Galán. Critical revision with substantial intellectual contributions: F.M. García-Padilla and M. Sánchez-Alcón. All the authors approved the final version for publication.

We would like to thank all the participating students and teachers who generously gave their time to fill in the questionnaire.

This study has been funded by the Teaching Innovation Unit of the University of Huelva in the call for funding educational research projects 2022-2023.